Editor’s Note: This science review was written by Kiley Pratt, a rising senior at Tufts University. Ms. Pratt is conducting research at the Division on Addiction this summer.

Cigarette cravings contribute to smoking frequency and smoking relapse for those trying to quit. Smokers experience cravings to varying degrees of intensity; they also have a wide range of perceptions about smoking and its consequences. Public health advocates sometimes leverage negative consequences as motivation to help quit attempts, but it is unclear how craving levels are related to conscious perception of consequences or smoking desirability. This week, ASHES reviews a study by Lauren Bertin and colleagues which examined the relationship between cigarette cravings and perceptions of the negative consequences of smoking.

What is the research question?

How do beliefs and attitudes about cigarette smoking affect cravings?

What did the researchers do?

The authors recruited 103 participants with diagnosed nicotine dependence. First, participants answered questions about their attitudes and beliefs regarding the negative consequences of smoking by responding to statements such as, “Smoking is taking years off my life” or “People think less of me if they see me smoking.” Then, participants responded to imagery which could potentially trigger smoking urges. They closed their eyes, listened to a 60 second script, and were asked to visualize either going to the dentist before a painful procedure (stress cue), having a cigarette following a meal (smoking cue), or changing a light bulb (neutral cue). Participants reported their cigarette cravings before and after the exposure. The researchers used repeated measures ANOVA to compare the effects of the type of exposure (stress, smoking, or neutral) time, and initial beliefs about negative consequences on cravings.

What did they find?

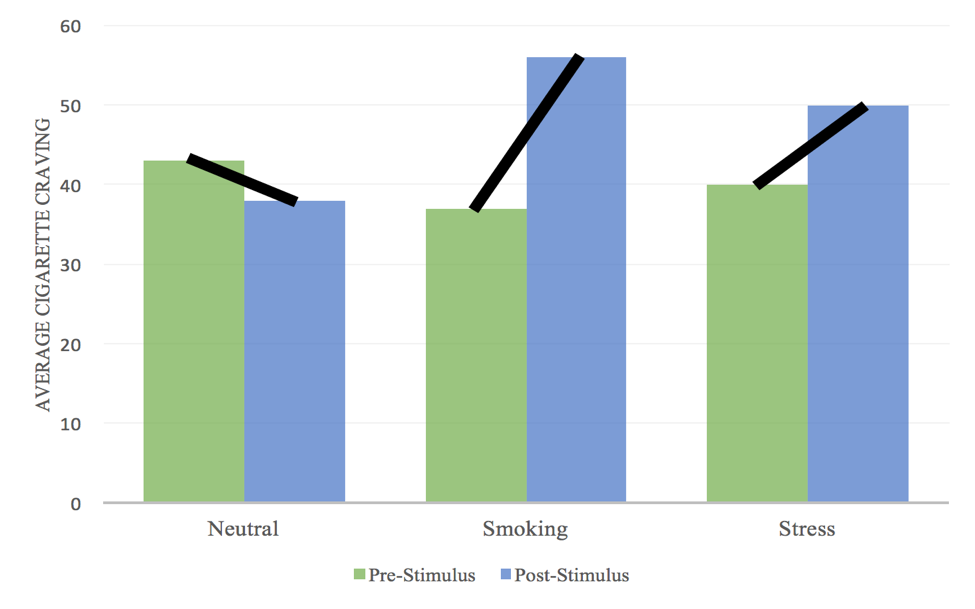

Overall, participants craved cigarettes more following exposure to smoking and stress imagery, and less following exposure to neutral imagery (see Figure). Across all three conditions, at the beginning of the study, participants craved cigarettes less if they felt that cigarettes cause negative consequences. Participants who initially felt that cigarettes lead to negative outcomes showed an interesting pattern: because they had weaker cravings before the visualizations, they experienced a much larger craving increase over the course of the experiment than other participants.

Why do these findings matter?

These results suggest that, no matter how undesirable a smoker may rate the consequences of smoking, they will still be susceptible to events that trigger cravings. In terms of interventions, providers could focus on strategies to avoid these events. They could also teach visualization as a strategy for minimizing craving, such as visualizing neutral images when a craving is coming on.

Figure. Self-reported average level of cravings among each stimulus group before and after exposure to different cues and stimuli; the pre/post differences for each stimulus group were statistically significant, as illustrated by the slope marking lines. Click image to enlarge

Every study has limitations. What about this one?

There are many other important attitudes and factors which could play into cravings which were not discussed or investigated in this study. Also, this study was conducted in a laboratory; we cannot say for certain whether these results would replicate in a real-world setting.

For More Information:

To speak with someone or discover tools for quitting and maintaining abstinence from smoking, visit Smokefree. Or, visit Your First Step to Change: Smoking for first steps and a more personalized guide. For additional tools, please visit the BASIS Addiction Resources page.

–Kiley Pratt

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.