There are a number of effective, evidence-based treatments available for individuals suffering from alcohol use disorder. However, relapse rates are often high even for effective treatments, and not all individuals experience the same amount of relief from the standard treatments. In addition, people with alcohol use disorder (AUD) tend to have more health issues than those without AUD, which can complicate recovery. Some have suggested that including an exercise regimen in the treatment plan for individuals with AUD might improve outcomes and alleviate some of these health issues. Kirsten Roessler and her colleagues tested out this idea using a large randomized controlled trial of treatment seekers in Denmark. This week, The DRAM reviews their work.

What was the research question?

Does adding an exercise regimen to treatment for individuals with alcohol use disorder impact their alcohol intake at six months after initiating treatment?

What did the researchers do?

Roessler’s team recruited 172 participants from two outpatient alcohol treatment centers in Denmark and randomly assigned them to one of three groups: treatment as usual, treatment with an additional supervised group exercise twice a week, and treatment with an additional individual exercise plan. At the beginning of treatment and again at the 6 month mark, participants completed the Timeline Follow-Back questionnaire to estimate their alcohol consumption and days without drinking in the past 30 days. They also completed the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) as a measure of their physical activity.

What did they find?

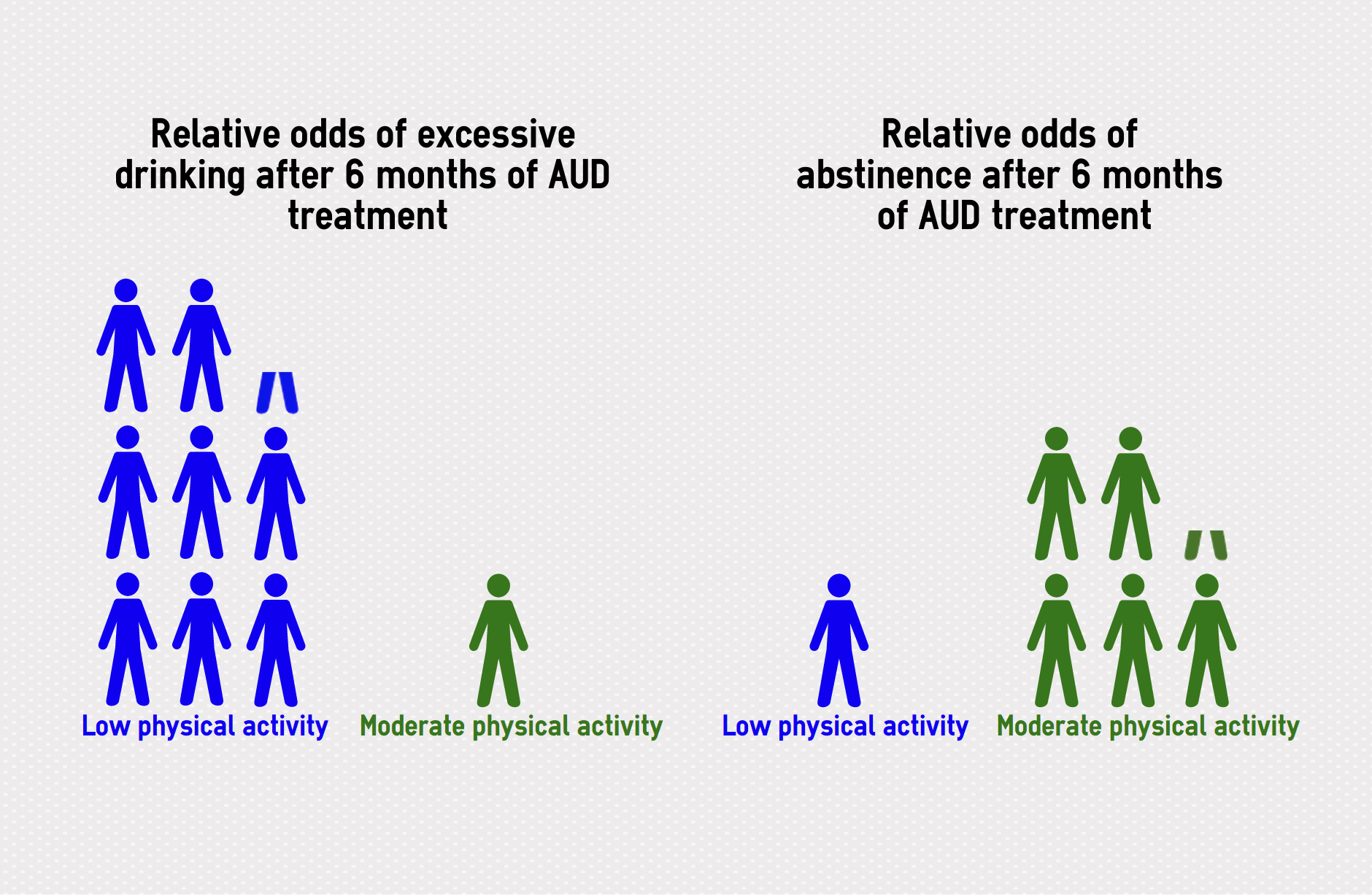

Participants in all three groups showed improvements on alcohol consumption outcomes. These improvements were not significantly different between the control and either intervention group, suggesting that the exercise regimens did not improve the outcome of the AUD treatment. However, when the researchers examined the participants’ IPAQ scores, they found that individuals who had moderate levels of physical activity (those who exercised at least five days a week and achieved between 600 and 3000 metabolic equivalent minutes per week) were less likely to drink excessively at the 6-month mark than participants who had low levels of physical activity. Those with moderate physical activity were also 5.2 times more likely to report abstinence at six months than their low physical activity counterparts. The study did not report comparisons between low and high physical activity.

Figure. The above infographic compares the likelihood of a drinking-related outcome between people with different levels of physical activity. More stick figures means this outcome is more likely for people in this group. For example, on the left, there are 8.3 people with low physical activity that experience excessive drinking for every one person with moderate physical activity after 6 months of treatment. It is important to note that these likelihoods are still an improvement compared with the beginning of treatment. Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

This study was part of a larger project to discover practical ways of enhancing AUD treatment using interventions that could be easily and broadly integrated into clinical practice. While these findings do support a connection between greater physical activity and better treatment outcomes for individuals with alcohol use disorder, the two specific exercise programs implemented in this study do not seem to enhance treatment outcomes.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations in this study?

The exercise facilitated by the intervention in this study was limited to running. A more flexible and individualized exercise plan might have a different impact as participants would be able to pick the activities they enjoy more. Importantly, a fairly large proportion of participants dropped out of the study before completion (37.1%), meaning that finding a difference between the control and two exercise groups is more difficult. Importantly, a high dropout rate might indicate that the treatment plan in its current form is not tolerable for the people that it’s meant to help.

For more information:

To learn more about the impact of alcohol in your life, check out the Rethinking Drinking page by the National Institutes of Health. If you are seeking guidance for yourself or a loved one regarding problems with alcohol, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism treatment page has information that can help.

— Rhiannon Chou Wiley

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

Solange Pilares November 15, 2017

I am a Substance Abuse Counselor who does group therapy at an intensive outpatient treatment facility for dual diagnosis patients. I would like to say that what I have seen so far is that patients who incorporate regular physical activities to their daily routines are the more likely to maintain sobriety 6 months after completion of treatment, which supports this study. However, is not only physical exercise (running, aerobic exercise) that helps with sobriety but daily practice of meditation, gratitude and attendance to 12step programs, counseling among others as well. Thanks a lot for you publications and studies. I really enjoy them because it helps me to learn more about what I can do to improve my patient’s treatment outcomes.