Effective strategies exist to treat opioid and alcohol use disorders, yet access to treatment is often limited by service availability as well as the stigma associated with seeking help. One approach to overcome these challenges is to make these services available through collaborative care. Collaborative care involves integrating behavioral health into primary care. This week, The DRAM reviews a study on collaborative care by Katherine Watkins and her colleagues.

What was the research question?

Does use of a collaborative care model lead to higher treatment engagement and better outcomes among patients with opioid or alcohol use disorders than a usual care model?

What did the researchers do?

The researchers recruited 377 participants who screened positive for possible opioid use disorder and/or alcohol use disorder during a primary care visit at one of two large health centers in Los Angeles, CA. To be included in the study, participants had to be over 18, actively using, and not in treatment for substance use. This study randomly assigned participants to receive either Collaborative Care (CC) or Usual Care (UC). Participants in the CC group met with a care coordinator who helped them access treatment and checked in with them regularly about substance use and any missed therapy appointments. Treatment options included motivational interviewing paired with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and/or medication (buprenephrine/naloxone for opioid use or naltrexone for alcohol use). Participants in the UC group received contact information for treatment services but did not meet with care coordinators. Researchers then contacted participants in both groups six months later and assessed whether they had engaged in treatment since baseline and whether they had used any substances in the past 30 days.

What did they find?

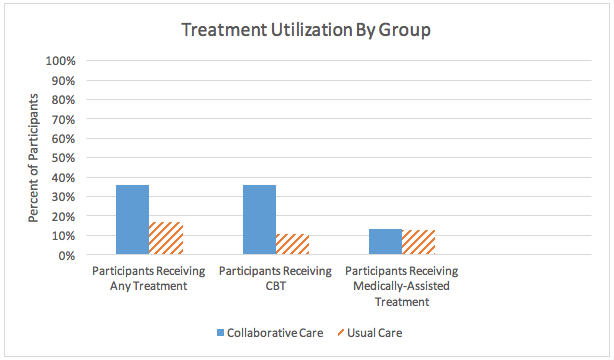

At follow-up, participants in the CC group were less likely to report alcohol or other substance use in past 30 days than participants in the UC group (74% compared to 84%). As Figure 1 shows, the percentage of participants who received treatment for their alcohol and/or opioid use was significantly greater in the CC group (39%) than the UC group (17%). This difference reflects greater engagement in CBT among the CC group.

Figure. Each bar in the graph above represents a percentage of participants receiving a specific type of treatment during the time between baseline and follow-up. The solid blue column represents participants from the CC group. The orange column with diagonal lines represents participants from the UC group. Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

Studies like this demonstrate that integrating substance use disorder treatment into primary care is an effective way to increase service access. Additionally, the higher proportion of participants receiving CBT in the CC group suggests that having a provider talk to participants about services might have helped to destigmatize mental health treatment; however, this effect might also be attributable to the convenience of the setting or the authority of the primary care provider. It is important to note that half of the sample in the current study was homeless. This suggests that the CC intervention encourages treatment engagement even within vulnerable populations with limited access to resources.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations of this study?

Behavioral health services are already integrated into the hospital used in this study, which limits the generalizability of the results. Hospitals without these services may require additional resources for CC implementation or have difficulty fully integrating these services. Additionally, the researchers were unable to confirm whether patients filled their prescriptions. Therefore, any conclusions about medication-assisted treatment are limited by reliance on data about prescriptions provided, rather than prescriptions filled.

For more information:

Learn more about mental health prevalence rates with the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

Learn more about alcohol use with the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Learn more about opioid use with the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

For help considering whether to seek a formal evaluation on mental health or substance use problems, visit our page on addiction resources.

— Pat Williams

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.