Almost 1.4 million adults in the United States, about 0.6% of the population, identify as transgender. Transgender individuals identify as a gender that is different from what they were assigned at birth. This includes gender nonconforming or non-binary individuals who do not identify solely as a man or a woman. To be inclusive, we will use the term “transgender or gender nonconforming” or TGNC. TGNC individuals, and especially transgender women of color, often experience social stigma and discrimination, limited access to health care, and violence. Because of these experiences, TGNC individuals might be at increased risk for substance use disorders. This week, as part of our Special Series on Addiction among the LGBTQ+ Community, STASH reviews research by Ayden Scheim and his colleagues that examined past year illicit substance use among TGNC individuals.

What was the research question?

What is the prevalence of past year illicit drug use among TGNC individuals, and what factors are associated with illicit drug use?

What did the researchers do?

Scheim and his colleagues used data from the Trans PULSE Project conducted in Ontario, Canada from 2009-2010. This community-based participatory research project surveyed TGNC individuals using respondent-driven sampling. Participants (N = 406) were eligible for the study if they self-identified as transgender and were older than 16. To examine illicit drug use differences within the TGNC population, the researchers separated participants into 2 categories: transmasculine (assigned male at birth and identify as female or gender nonconforming) and transfeminine (assigned female at birth and identify as male or gender nonconforming). To approximate a cisgender population, or individuals who identify as the same gender they were assigned at birth, researchers used age-adjusted data from the 2009-2010 Canadian Community Health Survey. Participants indicated what illicit substances they’ve used during the past year. Researchers focused on “high-risk” drug use, like crack or powder cocaine, crystal methamphetamine, ketamine, and heroin. Support systems were assessed using the Medical Outcomes Study scale. Social stigma and exclusion was assessed through reported experiences of transphobia on an 11-item scale.

What did they find?

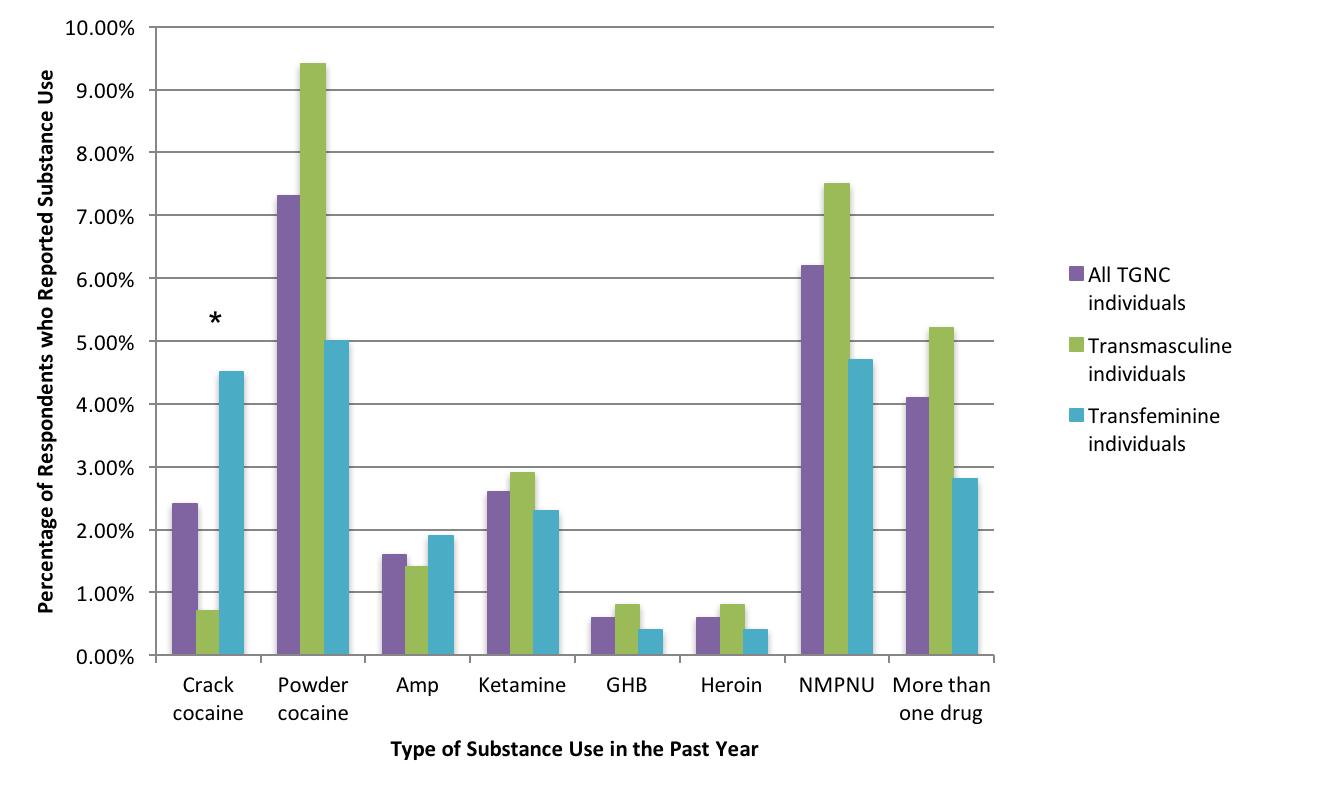

About 12% of TGNC individuals reported using at least one high-risk illicit drug during the past year. Transfeminine individuals (assigned male at birth and identify as female or gender nonconforming) were significantly more likely to report past year crack cocaine use than transmasculine individuals (assigned female at birth and identify as male or gender nonconforming), but other gender differences were not statistically significant (see Figure 1). Notably, TGNC individuals were 5-6 times more likely to report past year cocaine or amphetamine use compared to cisgender individuals. Being white, experiencing homelessness, and being a victim of transphobic violence was associated with increased likelihood of drug use.

Figure. Percentages of TGNC Ontarians who reported illicit substance use in the past year. Click image to enlarge. (Amp = amphetamines, NMPNU = non-medical prescription narcotics use, *Percentages are different among the groups at a statistically significant level.) Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

Understanding substance use patterns in TGNC populations is necessary to inform treatment and outreach. A cultural shift in medical and mental health treatment is also necessary for such treatment to be effective. Along with homosexuality, gender nonconformity was described as a mental pathology in the DSM-3 and was only removed in the current DSM-5. TGNC individuals often face limited trans-affirmative treatment options, and even are denied care because of their gender identity. In what hopefully is an initial step towards rectifying these harms, the American Psychological Association published guidelines in 2015 for clinicians on how they can respectfully treat TGNC patients and build positive working alliances.

Every study has limitations. What were the limitations in this study?

The researchers only had information about past year illicit drug use, but not frequency of use or prevalence of substance use disorders. Therefore, it is only possible to compare rates of substance use between cisgender and TGNC populations, not substance use disorders. Additionally, the CCHS currently does not have any way to identify TGNC respondents, so it is likely that some participants in that sample were not cisgender. This limitation would underestimate the differences between the groups.

For more information:

Find the original publication abstract here.

If you want to know how you can be a better ally to TGNC individuals, this guide is a good place to start.

For TGNC individuals and other members of the LGBTQIA+ community seeking medical and mental health treatment, support groups, and more in the Boston-area, check out Fenway Health!

If you or a loved one has a problem with substance use, please visit our addiction resources here.

— Layne Keating

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.