For many people, faith and religion are important parts of life and can have a profound effect on their choices. Although many religions condemn, if not outright forbid, recreational gambling, only a handful of studies have examined the relationship between religion and gambling. Even fewer studies have examined this relationship among young adults, whose minds often are still developing, making them more impressionable in a variety of ways. This week, THE WAGER reviews a longitudinal study by Jeremy Uecker and Charles Stokes that examined how religious background and participation relates to gambling among young adults.

What is the research question?

How does religious background and participation among young adults in the U.S. relate to their gambling and experience of gambling-related problems?

What did the researchers do?

Drawing from a nationally representative study, the authors examined self-report data from 13,980 young adults at two points in time (Time 1 = 1994-1995, Time 2 = 2001-2002). From Time 1, the authors looked at each respondent’s religious affiliation (e.g., conservative Protestant, Jewish, no religion), how often they attend religious services, the proportion of conservative Protestants in their community, and their thrill-seeking behavior. From Time 2, the authors looked at whether the respondent engaged in any form of gambling and, if so, whether it amounted to problem gambling (e.g., gambled to relieve uncomfortable feelings). They used multi-level modeling to assess whether participants’ religious background at Time 1 predicted gambling behavior at Time 2.

What did they find?

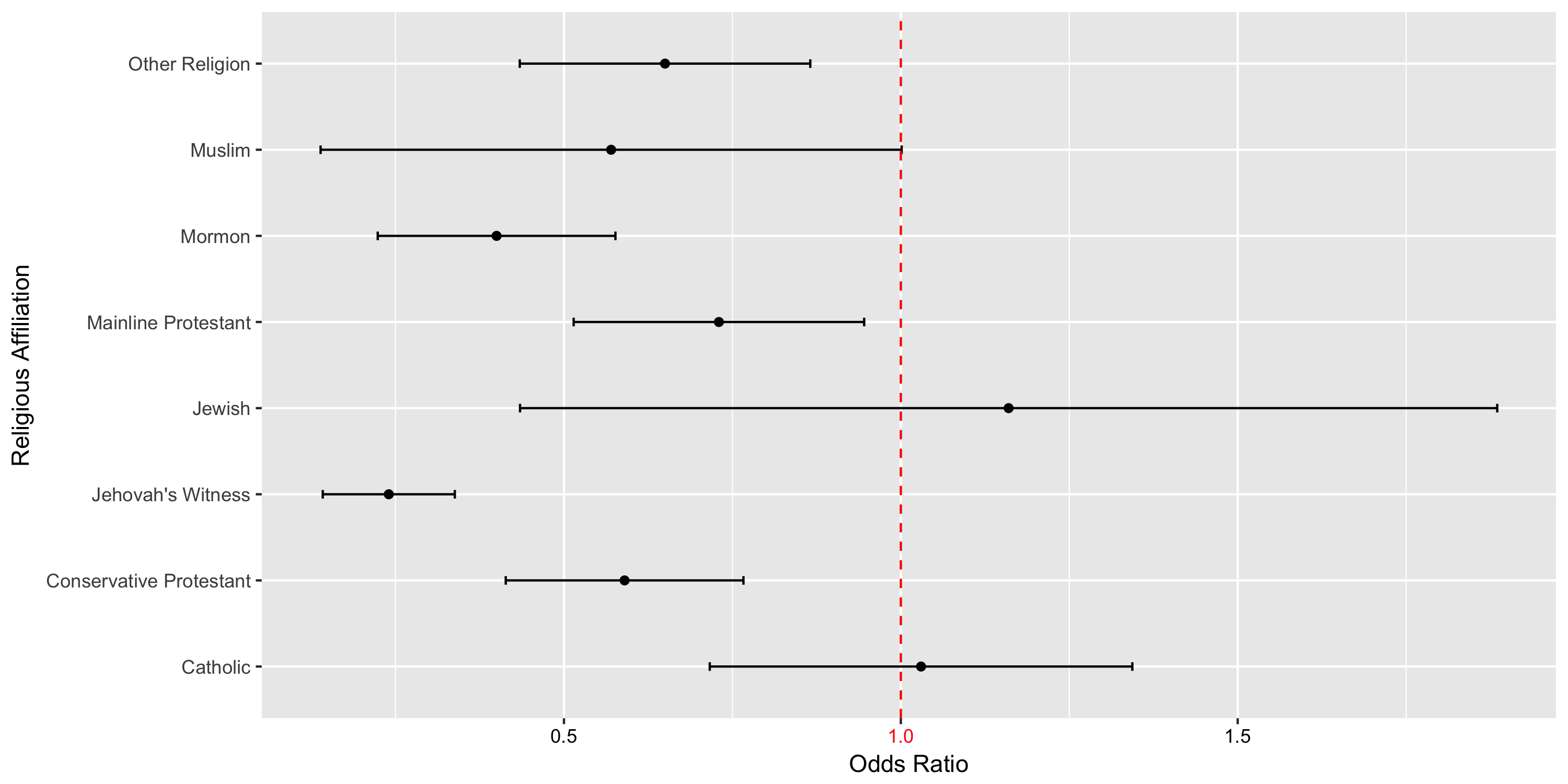

Young adults with a conservative Christian background (particularly Mormons and Jehovah’s Witnesses) were less likely to have ever gambled compared to young adults from other/no religious backgrounds (see Figure). Regardless of their faith and thrill-seeking behaviors, young adults who attended religious services more regularly and had a larger proportion of conservative Protestants in their community were less likely to have ever gambled. Approximately five percent of respondents reported gambling-related problems. Among respondents who reported gambling, those who attended religious services sporadically at Time 1 were more likely than non-attenders to report gambling-related problems at Time 2, regardless of their religious affiliation.[1] Kids who attended services weekly had the same risk as kids who didn’t attend at all.

Figure. Odds of Gambling at Time 2 by Religious Affiliation at Time 1. Click image to enlarge.

Figure. Odds of Gambling at Time 2 by Religious Affiliation at Time 1. Click image to enlarge.

- The circles in the figure represent odds ratios and the lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. Statistically significant odds ratios are those that do not intersect with a value of one. If a group’s entire line is located below 1, respondents from that religion were less likely than respondents with no religious affiliation to report any gambling at Time 2.

- The authors also controlled for the percent of conservative Protestants in the community, religious attendance, how important religion is to the subject, thrill seeking behavior, gender, age, race-ethnicity, parents’ education, hours worked per week, marital status, and personal earnings.

Why do these findings matter?

Starting to gamble early in life is associated with increased risk for gambling-related problems. This study’s findings support the idea that religion can help kids avoid gambling early, which might help prevent gambling addiction later on. However, the protective effects of religious attendance disappeared among kids who attended services sporadically and did experiment with gambling. This surprising finding needs to be replicated before we can begin to make sense of it.

Every study has limitations. What about this one?

This study used self-report data, meaning respondents could have exaggerated, forgot, or even lied about the extent of their religious practices and gambling behavior. The researchers only tracked the gambling behavior of respondents during their young adulthood (18-25 years of age) when some forms of gambling might be off-limits (e.g., casinos) and many of the respondents might not have much money with which to gamble.

For more information:

If you are concerned that you or a loved one has a gambling problem, please visit the National Council on Problem Gambling. We provide free, anonymous resources, including gambling screening and self-help tools. You can find them here.

— Timothy Edson

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

________________

[1] Sporadic attendance means attending religious services less than once a month to three times a month.

Chris Countryman, LCSW May 24, 2017

Hard to believe they did not include Catholics in the study since we are known for our gambling-related church fundraising.

Tim Edson May 24, 2017

Thanks for the input, Chris. The authors did include Catholics in their study (see the bottom odds ratio listed in Figure 1). The authors hypothesized that Catholics would be associated with an increased likelihood of gambling for the exact reason you mentioned (gambling related fundraising). However, their results show that respondents who were Catholic were not significantly more or less likely to report having gambled than respondents with no religious affiliation.

Fiona May 25, 2017

I’m confused by what appear to be two opposing statements in the article. “This study’s findings support the idea that religion can help kids avoid gambling early, which might help prevent gambling addiction later on. and “Kids who attended services weekly had the same risk as kids who didn’t attend at all.”

Tim Edson May 25, 2017

Hi Fiona,

Thanks for your question.

Those two statements are referring to two different gambling-related outcomes: 1) whether the respondent reported gambling at all; and 2) among respondents who did gamble, whether they reported gambling-related problems. The study found that kids who attended religious services weekly were less likely than non-attenders to have gambled at all. However, those who did gamble had the same risk of gambling-related problems as non-attenders.