About 85% of individuals experiencing incarceration in the United States meet criteria for alcohol or substance use disorders, or have extensive documented drug or alcohol use, which elevates risk for reincarceration. To combat this problem, many jurisdictions attempt to treat addiction during incarceration or as an alternative to incarceration. This week, as part of our Special Series on Mindfulness and Addiction, STASH reviews research by Katie Witkiewitz and her colleagues that assessed the effectiveness of mindfulness-based relapse prevention (MBRP) in preventing relapse for women in residential addiction treatment.

What was the research question?

Does MBRP reduce drug use frequency and symptoms of drug use disorder after addiction treatment, when compared to standard relapse prevention?

What did the researchers do?

Witkiewitz and her colleagues recruited participants (N = 105, all women) at a residential treatment facility serving individuals with a history of illegal activity. Though the program was an alternative to incarceration, most residents previously served some time in jail or even prison. The research team randomly sorted participants into 2 groups: MBRP and Relapse Prevention (RP). The MBRP intervention focused on helping participants identify substance use triggers and craving and learning how to use mindfulness and meditation (e.g., breathing exercises, sitting or walking meditation, body awareness) to avoid reacting to these feelings. The RP intervention was based on work by Daley and Marlatt and the Coping Skills Training Guide, and its primary goals were to help participants identify potential relapse situations and learn behavioral or cognitive skills to prevent relapse. Researchers administered the 30-day Timeline Follow-Back and the Addiction Severity Index to measure frequency and consequences of substance use. They administered these assessments at the beginning and end of the 8-week treatment program and 15 weeks after the end of the treatment program.

What did they find?

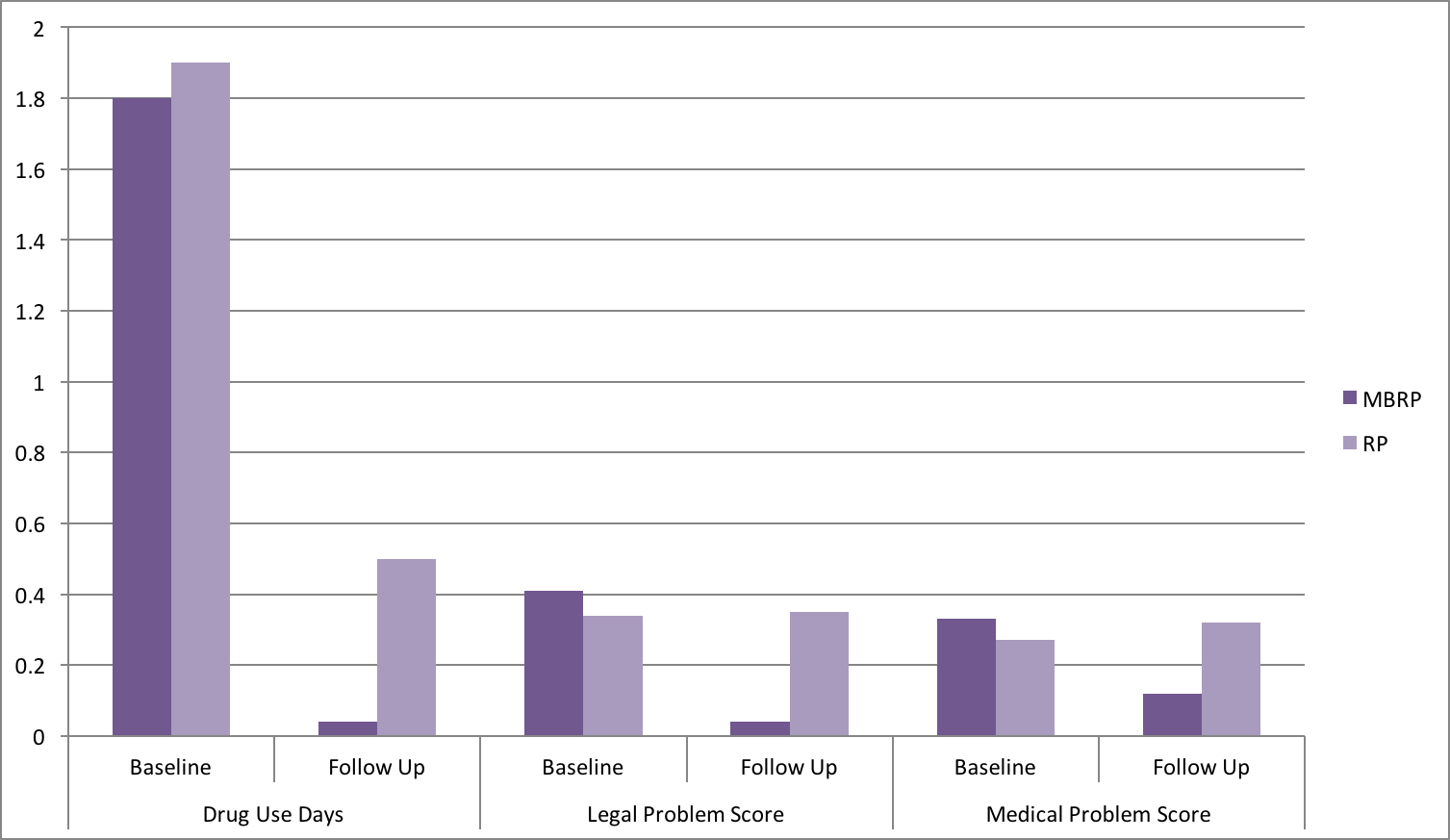

At follow up, only 6 participants in total reported any drug use: 5 participants in the RP group and 1 participant in the MBRP group. Among these 6 participants, those who received the MBRP intervention had 96% fewer days of drug use than those who received the RP intervention. Participants who received the MBRP intervention also reported significantly less legal and medical problems. However, there was not a significant difference in number of consequences related to drug use between intervention groups.

Figure. Change in number of mean drug use days, legal problem score, and legal medical score for participants in the MBRP and RP groups. All changes from baseline to follow up were significantly different between the MBRP and RP groups. Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

These results suggest that MBRP might be more effective than more traditional relapse prevention practices, though both interventions appear to be effective, at least for the 15 week follow up period. Additionally, these results reinforce previous research which found referring individuals with a history of drug-related illegal activity to substance use treatment, instead of incarceration, to be effective in limiting substance use relapse. Further research is necessary to examine the effect of MBRP on repeat arrests or incarcerations.

Every study has limitations. What were the limitations in this study?

The sample size was relatively small and was limited to women with a history of illegal activity. Therefore, these results might not be generalizable to other genders or individuals experiencing substance use disorders who are not involved in the criminal justice system. Additionally, due to the environment, participants in the residential treatment facility were able to share information about the interventions across groups, and participants in the RP intervention were even able to take part in mindfulness meditation activities. This might have “contaminated” the design, which would minimize differences between the two conditions.

For more information:

Find the original publication abstract here.

If you or a loved one has a history of incarceration, Transitions Clinics can provide stigma-free health care for formerly incarcerated patients with chronic conditions, including referrals to housing and educational resources. You can find a location near you here.

If you or a loved one has a problem with substance use, please visit our addiction resources here.

— Layne Keating

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

Rohini April 19, 2017

What were the limitations associated with providing a clear participation distinction between the two types of relapse prevention? Why was participation in both allowed?

Layne Keating April 20, 2017

Thank you for your comment, Rohini!

Due to the restrictions of conducting research within a residential facility, it was impossible, and likely not ethical, for researchers to ensure complete separation between the two intervention groups. Therefore, participants receiving one intervention could potentially share that material with the other, and participants of either group could attend the mindfulness meditation exercises offered by the treatment center (independent from the MBRP intervention). Therefore, it is possible that these limitations resulted in reducing the difference between the two interventions, which limits the confidence with which researchers can claim that MBRP intervention was more effective than standard relapse prevention