Editor’s Note: We’re proud to announce that Dr. Dawn Sugarman will speak on the topic of “Gender-Specific Treatment for Substance Use Disorders” at this fall’s Addiction Medicine continuing medical education course, presented by the Division on Addiction through Harvard Medical School. In today’s article, we review research from Dr. Sugarman and her colleagues at the Alcohol and Drug Abuse Treatment Program at McLean Hospital.

Excess alcohol consumption is a serious public health concern and often requires inpatient treatment. Previous research has found that factors like gender, educational status, and marital status moderate alcohol treatment outcomes, historically defined by changes in how often and how much people drink. These results, however, have been inconsistent. Additionally, the National Institute on Drug Abuse has recently suggested expanding how we measure alcohol treatment outcomes to include impact on psychosocial functioning. In the DRAM this week, we review a study by Dr. Dawn Sugarman and her associates examining the association between baseline characteristics and multiple inpatient alcohol treatment outcomes.

What was the research question?

What baseline characteristics are associated with drinking frequency and psychosocial functioning a year after inpatient alcohol treatment?

What did the researchers do?

Sugarman and her colleagues recruited participants (n = 101) who received inpatient alcohol treatment and qualified for alcohol dependence based on the Structured Clinical Interview – DSM-II-R. Through interviews and self-report questionnaires, researchers collected demographic information, sexual abuse history, measures of self-efficacy and social support, and other clinical diagnoses at baseline, while participants were undergoing inpatient treatment. The researchers also followed up with participants monthly for 12 months following inpatient treatment completion, using the Timeline Followback to measure drinking. They defined two different outcomes of alcohol treatment: mean number of drinks per drinking day during the 12 month follow up period, and overall functioning, rated by interviewers on a 1-100 scale, the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) Scale. Sugarman and colleagues used path analysis to explore how these variables were related to one another and with the two outcomes, and we report a simplified version of their results here.

What did they find?

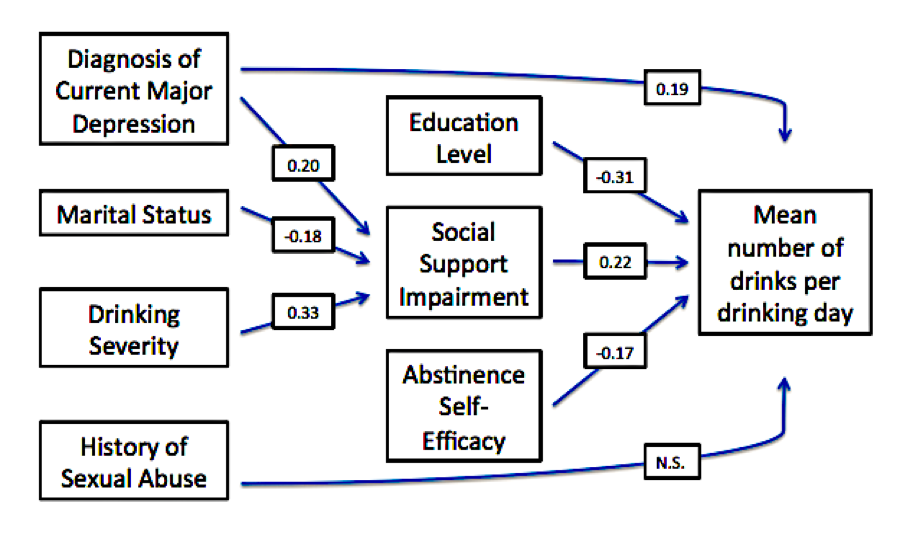

Sugarman and her colleagues created a model for each alcohol treatment outcome they measured. As Figure 1 shows, participants who were unmarried, had higher drinking severity, or had a diagnosis of major depression were more likely to report impaired social support than others. In turn, impaired social support, along with less education and low abstinence self-efficacy, predicted more drinks per day at follow-up. The researchers then turned to GAF scores. They found that only a history of sexual abuse was associated with lower GAF scores at follow-up.

Why do these findings matter?

By identifying risk and protective factors, clinicians can identify patient populations that might require more attention and resources to achieve positive treatment outcomes. Providers can then create individualized treatment plans to combat these risks. For example, if depression and drinking severity affect treatment outcomes through their impact on social support, then treatments might consider providing resources to foster social support within these groups. While multiple factors were associated with drinks per drinking day after treatment, only a history of sexual abuse was associated with global functioning. This suggests that treatment research needs to consider treatment outcomes more broadly and investigate the factors that impact these multiple domains of treatment outcome.

Every study has limitations. What were the limitations in this study?

The study sample consisted largely of well-educated white men. These results, therefore, may not be generalizable to other treatment populations. Additionally, the small sample size, and corresponding decreased statistical power, might have masked significant associations between variables and outcomes. These results should be validated with a larger sample.

Figure. Statistically significant Path coefficients between baseline characteristics and drinking frequency at follow-up (simplified from Sugarman et al., 2014). N.S. = not significant. Click image to enlarge.

For more information:

Find the original publication abstract here.

For a guide to accessing treatment for alcohol use, click here.

If you are worried you or a loved one has a drinking problem, visit our website for the First Step to Change: Drinking, a free, anonymous toolkit.

— Layne Keating

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.