People who misuse prescription opioids risk addiction, other kinds of illnesses, and death. Therefore, it is important to understand what predicts non-medical prescription opioid (NMPO) use. Brooke Arterberry and her colleagues used national survey data to examine how use of different substances, including tobacco, relates to different stages of NMPO use. This week, as part of our Special Series on Opioid Dependence and Recovery, ASHES reviews the tobacco findings from their study.

What was the research question?

Does early tobacco use and frequency of tobacco use relate to non-medical use of opioids?

What did the researchers do?

Arterberry and her colleagues analyzed data from Wave 1 (n = 43,093) and Wave 2 (n = 34,563) of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), conducted in 2001 – 2002 and 2004 – 2005 respectively. Researchers identified three different histories of NMPO use[1]: initiation (people who did not use at Wave 1 but did use at Wave 2), reinitiation (people who had stopped using by Wave I but started using again by Wave 2), and persistence (people who used at Wave 1 and Wave 2). The study also measured early onset of cigarette use (before age 14) and high-risk frequency of cigarette use (5-6 days/week) at Wave 1.

What did they find?

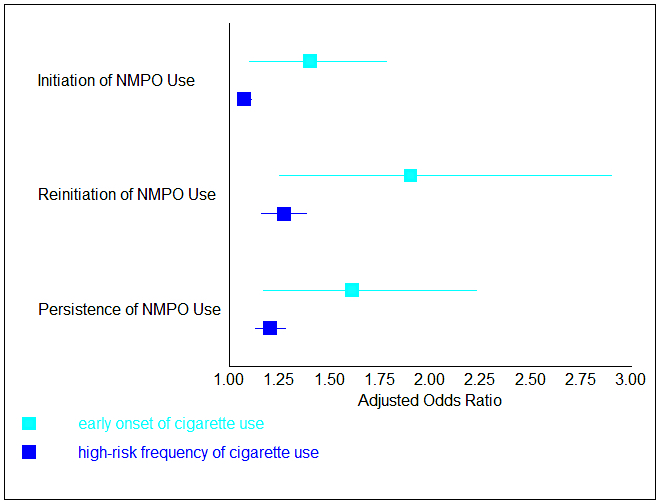

Individuals who started smoking before age 14 were 1.4 times more likely to initiate NMPO use, 1.9 times more likely to reinitiate NMPO use, and 1.6 times more likely to have persistent NMPO use than those who did not. In addition, those who smoked more frequently were more likely to initiate, reinitiate, and have persistent NMPO use (see Figure).

Figure. Adjusted odds ratios (boxes) and 95% confidence intervals (lines) for early onset and high-risk frequency of cigarette use among different types of NMPO use. These odds ratios indicate how likely a group (early onset or high frequency of cigarette use) is to have a certain outcome (initiation, reinitiation, or persistence of NMPO use). All of these effects are statistically significant. Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

By figuring out what predicts NMPO use, it is possible to develop targeted prevention and intervention programs that can identify and help at-risk populations. Additionally, most NMPO users obtain opioids from either their own doctor or through friends’ or family members’ prescriptions. Physicians can use the risk factors like early cigarette smoking to identify who might be at risk for NMPO use and adjust their prescribing practices accordingly.

Every study has limitations. What were the limitations in this study?

Though published in 2015, this study uses data from 2001-2005; however, from 1999-2014, both the amount of prescribed opioids and opioid overdoses have quadrupled. Therefore, it may be necessary to replicate these findings using more recent national survey data and assess whether the associations between early onset and frequency of cigarette use (and other substances) and NMPO have changed.

For more information:

For physicians interested in resources for safe opioid prescribing practices, please check out the AMA and NIH websites. If you believe that you or a loved one may have a problem with prescription opioid use, here are some resources and information on different types of opioid treatment programs. For additional tools, please visit the BASIS Addiction Resources page.

— Layne Keating

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

________________

[1] The NESARC defines non-medical use as using “to feel more alert, to relax or quiet nerves, to feel better, to enjoy [oneself], to get high, or just to see how [POs] would work.”