Alcohol misuse is a serious public health concern, currently the fourth leading cause of preventable death in the US. Previous research has found that African-American and Hispanic drinkers are more likely to report symptoms of alcohol dependence and negative consequences related to drinking than their white counterparts. Are these disparities the consequence of unequal access to treatment? This week, as part of our Special Series on Disparities in the Experience and Treatment of Addiction, The DRAM reviews a study by Nina Mulia and her colleagues, which used national survey data to measure disparities in alcohol treatment utilization.

What was the research question?

What ethnic or racial disparities exist in the need for and access to treatment for at-risk drinking?

What did the researchers do?

Mulia and her colleagues performed a secondary analysis on data from the first wave of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), conducted 2001-2002. They analyzed data from participants who met criteria for at-risk drinking or alcohol abuse (N = 9,116) but excluded those who met criteria for alcohol-dependence[1]. They also examined the use of alcohol-related services, including those provided by a medical professional, specialty treatment programs including inpatient, outpatient, and rehabilitation facilities, and alternative treatments like Alcoholics Anonymous, emergency room care, or help from a spiritual advisor.

What did they find?

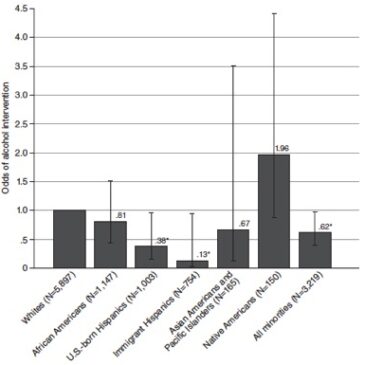

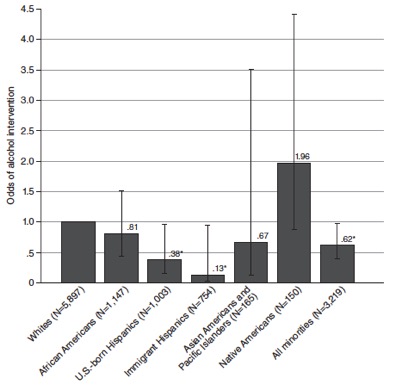

Individuals belonging to a minority race or ethnicity were more likely to experience negative consequences in relation to their drinking and more likely to participate in heavy drinking on a weekly basis. Despite a larger demonstrated need, members of a racial or ethnic minority were 1.6 times less likely to receive any alcohol intervention and half as likely to receive an intervention specifically from a primary care physician or specialty treatment program. This disparity was most prominent in Hispanic populations; US. born Hispanic individuals were 2.6 times less likely, and foreign-born Hispanic individuals were 7.7 times less likely to receive treatment when compared to White participants (see Figure 1).

Why do these findings matter?

Despite higher demonstrated need, racial-ethnic minorities are less likely to receive treatment for alcohol problems. To combat this disparity, it might be necessary to develop culturally competent prevention and intervention tools that draw upon inherent resilience. For example, Familia Adelante is a prevention program developed for Hispanic youth in the Los Angeles area. By emphasizing cultural pride and strong family connections along with education about stress and substance use, it produces durable and wide-ranging benefits for kids and their parents.

Every study has limitations. What were the limitations in this study?

Low treatment utilization overall during the study period (2.1% for white and 1.3% for minority participants) made it difficult to explore some specific demographic comparisons. Limited data were available on primary language, which can have a major impact on access to general health care resources. As mentioned earlier, this study excluded those participants that met criteria for alcohol dependence, so the researchers might have missed other disparities in severity and access to treatment.

Figure 1: The relative odds of receiving an alcohol intervention over a 4-year period as a function of racial/ethnic group. Whites are included as the referent group; values lower than 1 indicate lower odds of treatment compared to Whites, while odds higher than 1 indicate higher odds. Reprinted from Mulia et al. (2014).

For more information:

Find the original publication abstract here.

If you are worried you or a loved one has a drinking problem, visit our website for the First Step to Change: Drinking, a free, anonymous toolkit.

For more information and behavioral health resources specific to a particular race, ethnicity, or sexual orientation, check out SAMHSA’s website for Behavioral Health Equity.

— Layne Keating

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

[1] At-risk drinkers were defined by reports of drinking more than 3 or 4 drinks in a day or more than 7 or 14 drinks in a week for women and men respectively. Because they were interested in people at an earlier stage of illness, the researchers excluded participants who met criteria for alcohol dependence.

Dorothy Rose Forgione May 17, 2016

This study sounds as though some data used in the study was incomplete