About a third of motor vehicle fatalities involve driving under the influence (DUI) (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2013). Unfortunately, though rates of alcohol-related fatalities declined before the turn of the century, they have plateaued and held steady (Nelson & Tao, 2012). This week, as part of our Special Series on Driving under the Influence, we look at a paper suggesting that DUI is about more than just problem drinking: it may be a symptom of a larger pattern of criminal behavior related to psychiatric comorbidity (Nelson, Belkin, LaPlante, Bosworth, & Shaffer; 2015).

Methods

- This study included 743 repeat DUI offenders (of 1,220) admitted to a DUI treatment program in MA as part of their sentence (82% male).

- At baseline, counselors at the program administered the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (Kessler, Andrews, Mroczek, Ustun, & Wittchen, 1998) to assess lifetime and past year symptomology of 12 possible disorders:[1]

- Alcohol abuse and dependence, Drug abuse and dependence, Nicotine dependence, Pathological gambling, Major depressive disorder, Dysthymia, Bipolar disorder, Generalized anxiety disorder, Posttraumatic stress disorder, Conduct disorder, Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and Intermittent explosive disorder (IED).

- For the next five years, this prospective study tracked participants’ criminal records.

- Nelson and colleagues grouped criminal offenses into 8 categories, including motor vehicle offenses and DUI offenses specifically.

Results

- Within the full 5 years of follow-up:

- 4% of participants committed another criminal offense

- 2% committed a motor vehicle offense

- 5% committed another DUI offense

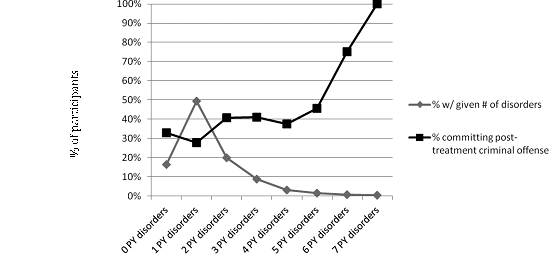

- Participants who met criteria for more psychiatric disorders at baseline were more likely to commit future offenses in general, particularly if they had disorders other than alcohol abuse or dependence. See Figure 1.

- Participants with a lifetime history of ADHD at baseline were more likely than others to commit a motor vehicle offense post-treatment.

Figure 1. Rate of diagnoses of past year (PY) disorder at baseline (gray line) and rate of any criminal offense post-treatment by number of (PY) disorders (black line). From Nelson et al. (2015).

Limitations

- DUI offense rates in the sample were low, reducing power to detect specific relationships between psychiatric comorbidity and DUI.

- Rates of DUI recidivism might be lower in this sample than in other populations of DUI offenders because these offenders completed a treatment program.

- Researchers only looked at criminal records from Massachusetts.

- Participants could have moved or had records in other states that were not taken into account.

Conclusion

The findings of this study suggest that DUI recidivists often suffer from comorbid mental health disorders that likely get in the way of treatment and contribute to re-offense. Therefore, treatment programs that only provide education and treatment related to alcohol use are not giving adequate attention to those other significant factors.

— Emily Shoov

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

References

Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Mroczek, D., Ustun, B., & Wittchen, H. U. (1998). The World Health Organization composite international diagnostic interview short‐form (CIDI‐SF). International journal of methods in psychiatric research, 7(4), 171-185.

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. (2013). Traffic safety facts 2011 data: Alcohol-impaired driving. Retrieved from http://www-nrd.nhtsa.dot.gov/Pubs/811700.pdf

Nelson, S.E., Belkin, K., LaPlante, D.A., Bosworth, L., & Shaffer, H.J. (2015) A Prospective Study of Psychiatric Comorbidity and Recidivism Among Repeat DUI Offenders. Archives of Scientific Psychology. 3. 8-17

Nelson, S. E., & Tao, D. (2012). Driving under the influence: Epidemiology, etiology, prevention, policy, and treatment. In H. J. Shaffer, D. A. LaPlante & S. E. Nelson (Eds.), The APA Addiction Syndrome Handbook (vol. 2, pp. 365–407). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Press.

———-

[1] ADHD and IED were added after the study began, so information is only available for 592 out of the 743 participants.