Many researchers have observed an association between disordered gambling and negative mood (e.g., Hodgins et al., 2005, Lorains et al., 2011). It stands to reason that addressing and reducing gamblers’ disordered behaviors might also improve their mood and outlook on life. This week The WAGER reviews a study that compares the effects of two brief interventions for disordered gambling on gamblers’ negative moods (Geisner et al., 2015).

Methods

- The researchers randomly sampled 6,457 college students at a large university on the West Coast of the United States.

- A total of 139 students met the criteria for inclusion in this study, in that they met criteria for gambling problems, agreed to undergo treatment for gambling problems, and completed the assigned treatment.

- The researchers randomly assigned participants to one of three treatment groups: personalized feedback intervention (n = 48), cognitive behavioral intervention (n = 43), and assessment-only control (n = 48).

- Participants in the personalized feedback intervention group attended a single session as treatment. Participants in the cognitive behavioral intervention group attended between either four or six sessions, one session per week.

- Both before treatment and after in a six-month follow-up, the researchers measured depression, anxiety, and hostility using the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI, Derogatis, 1993).The researchers summed these scores to create a measure of overall psychological distress.

- The researchers used analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) to compare the effects of the interventions on the participants’ combined BSI scores.

Results

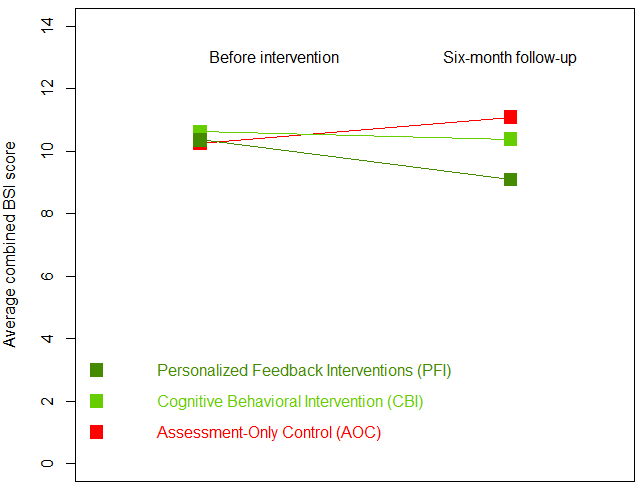

- The researchers observed a significant difference between change in BSI in the personalized feedback group and the corresponding change in BSI in the control group (see Figure 1).

- In the six-month follow-up, personalized feedback participants reported significantly lower BSI scores than control participants. Overall, they reported more improvement in their negative moods over the six months than the control group.

- On the other hand, the cognitive behavioral group did not report more or less improvement in their moods than the control group.

Figure. Average BSI scores for the three treatment groups, both before intervention and in the six-month follow-up. Click image to enlarge.

Limitations

- The sessions for the personalized feedback participants were between 60 and 90 minutes long, while the sessions for the cognitive behavioral participants were 60 minutes long. It is not clear how much of the differences between the groups in terms of effectiveness can be attributable to these differences in “dosage.”

- The data set was limited to a pre-intervention measurement and a six-month follow-up. It is unknown whether the interventions had any lasting effects beyond the six-month scope.

- The recruitment was limited to a college-aged population at a single school. The results may not generalize to other age groups or localities.

Conclusion

Previous studies have shown that personalized feedback and cognitive therapy can be used as interventions for lessening the problems created by disordered gambling. It is not surprising that these interventions appear to have benefits beyond just the consequences of gambling by themselves. The Internet is filled with anecdotes and personal testimony of people quitting harmful or even just time-consuming activities (e.g., Candy Crush Saga) and feeling better about themselves and about life afterwards. Although the personalized feedback approach showed benefits when compared to assessment only, the cognitive behavioral therapy did not. However, we should not dismiss CBT as non-effective. It might be that with a longer time frame (measured in years, as opposed to months), comparable dose, or a larger sample size, we may find that both work just as well at helping clients manage their gambling and improve their moods.

— Matthew Tom

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

References

Derogatis, L. R. (1993). BSI, brief symptom inventory: Administration, scoring & procedures manual. National Computer Systems.

Geisner, I. M., Bowen, S., Lostutter, T. W., Cronce, J. M., Granato, H., & Larimer, M. E. (2015). Gambling-Related Problems as a Mediator Between Treatment and Mental Health with At-Risk College Student Gamblers. Journal of Gambling Studies / Co-Sponsored by the National Council on Problem Gambling and Institute for the Study of Gambling and Commercial Gaming, 31(3), 1005–1013.

Hodgins, D. C., Currie, S. R., & el-Guebaly, N. (2001). Motivational enhancement and self-help treatments for problem gambling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69(1), 50–57.

Lesieur, H. R., & Blume, S. B. (1987). The South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS): A new instrument for the identification of pathological gamblers. American Journal of Psychiatry, 144(9).

Lorains, F. K., Dowling, N. A., Enticott, P. G., Bradshaw, J. L., Trueblood, J. S., & Stout, J. C. (2014). Strategic and non-strategic problem gamblers differ on decision-making under risk and ambiguity: Decision-making in problem gambling. Addiction, 109(7), 1128–1137.