Most married couples share smoking status – they either both smoke or both abstain. But in some marital relationships, one partner tries to quit but the other does not. In these relationships, research shows that smoking cessation is particularly difficult and relapses are common (Homish & Leonard, 2005). One factor that has the potential improve these odds is partner support for quitting. However, research in this area is mixed (see Collins, Emont, & Zywiak, 1990), and no research has examined the role of more general spousal support on smoking behavior and cessation across time. In this third installment of our Special Series on Addiction within Relationships, this week’s ASHES reviews a longitudinal study that examined the role of general partner supportiveness on smoking behaviors across time (Derrick, Leonard, & Homish, 2013).

Methods

- Researchers analyzed data from the Adult Development Study, a community sample of newlyweds followed for the first nine years of marriage.

- The current sample consisted of 333 couples in which at least one partner reported smoking at some point during the study.

- At each of 6 waves, researchers assessed the following measures:

Results

- Tobacco use decreased across time.

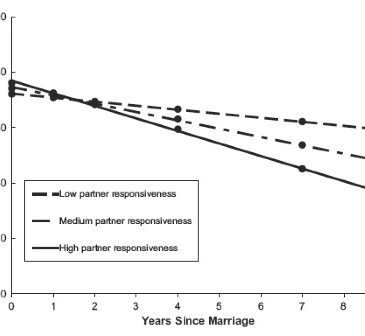

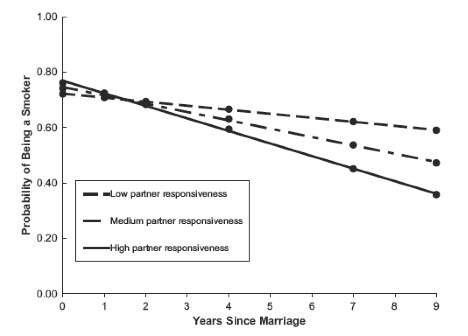

- As Figure 1 shows, participants who perceived their partners as highly supportive at baseline were more likely to cease smoking over time. The odds ratio for the support by time interaction was 0.94 (95% confidence interval = 0.88 – 0.99).

- For each one point increase in perceived supportiveness, participants’ likelihood of still smoking at the end of the study (i.e., year 9) decreased by 38%.

- Changes in perceived supportiveness across time also predicted smoking status; at any given time point, participants’ likelihood of smoking was lower if their ratings of partner support had increased from a previous timepoint.

Figure. Smoking status across time by baseline perceived partner support (reproduced with permission from Derrick et al., 2013). Click image to enlarge.

Limitations

- The sample had high attrition – only 38% of the original sample remained at year 9. Although methods were used to account for missing data, there might have been undetected systematic influences on drop-out that also related to smoking outcome. For instance, participants who were still smoking might have been more likely to drop out of the study.

- Changes in perceived support across time related to smoking status, but only concurrently (i.e., at the same time point as smoking status). Thus, we cannot assess whether these changes decreased smoking or whether decreases in smoking improved perceived supportiveness.

Conclusions

This study found that general perceived partner supportiveness predicted decreases in smoking within couples across time. These results suggest that, for successful smoking cessation, feeling supported in your relationship might be just as important, if not more important, than whether you partner specifically supports your decision to quit smoking. These results add to an expanding body of literature linking social support to health and well-being (e.g., Homish & Leonard, 2008). Future research needs to assess both general supportiveness and specific support for quit attempts within couples to determine the relative importance of these constructs.

–Sarah Nelson

Collins, R. L., Emont, S. L., & Zywiak, W. H. (1990). Social influence processes in smoking cessation: postquitting predictors of long-term outcome. Journal of Substance Abuse, 2(4), 389-403.

Derrick, J. L., Leonard, K. E., & Homish, G. G. (2013). Perceived partner responsiveness predicts decreases in smoking during the first nine years of marriage. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 15(9), 1528-1536.

Homish, G. G., & Leonard, K. E. (2005). Spousal influence on smoking behaviors in a US community sample of newly married couples. Social Science & Medicine, 61(12), 2557-2567.

Homish, G. G., & Leonard, K. E. (2008). Spousal influence on general health behaviors in a community sample. Am Journal of Health Behavior, 32(6), 754-763.

Schaefer, M. T., & Olson, D. H. (1981). Assessing intimacy: The PAIR Inventory. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 7, 47–60.

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

________________

1 This concept was measured using the emotional intimacy subscale of the Personal Assessment of Intimacy in Relationships (PAIR: Schaefer & Olson, 1981).

2 The researchers used multilevel models that accounted for the fact that data were nested within couple.