Many countries, including the United States, have developed classification systems for drugs based on their estimated risk for abuse, dependence, and negative consequences. However, it is not clear if these official systems reflect regular users’ opinions regarding the harmfulness of different drugs. Today’s STASH reviews a study that investigates how well official UK and US drug harmfulness classifications reflect regular drug users’ opinions of drug harmfulness (Morgan, Noronha, Muetzelfeldt, Fielding & Curran, 2013).

Methods

- The researchers posted a survey announcement online, and passively recruited 5,691 individuals (76% males) from over 40 countries to complete an online survey of their beliefs about the harms of 15 commonly used drugs or drug categories (e.g., hallucinogens such as Mescaline, Amphetamines such as Dexedrine, and Opiates such as heroin)..

- Participants were eligible to rate the harms of a particular drug if they reported to be regular users of this specific drug. The number of regular users for specific drugs varied from 99 (i.e., cocaine) to 3187 (i.e., mild stimulants).

- Participants assessed the following drug-specific harms [1]:

- Short-term and long-term physical risk (assessed separately)

- Risk of injecting

- Risk of physical and psychological dependence (assessed separately)

- Risk of bingeing

- Risk to society

- The researchers examined the correlation between US classification of illicit drugs and regular users’ perceived harms of specific drugs.

Results

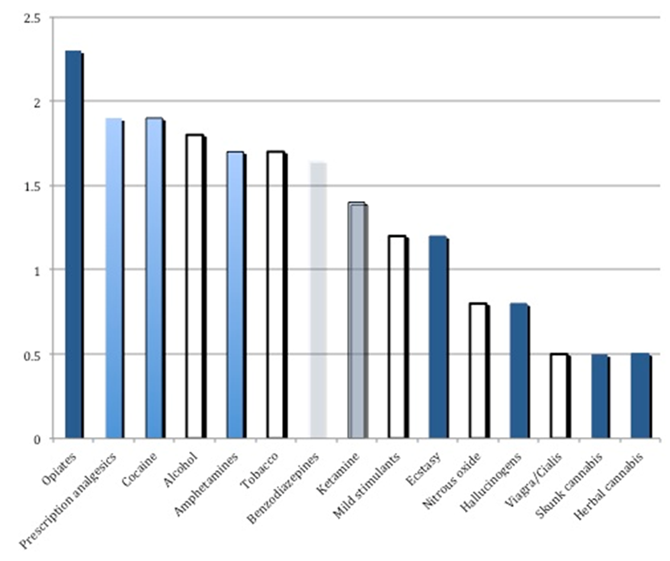

- Figure 1 shows that although official rankings suggest otherwise, regular users ranked alcohol and tobacco within the top ten most harmful drugs.

- On the contrary, participants rated cannabis and ecstasy as low risk substances, even though the official classification places them in the most risky category.

- Researchers found no statistical correlation between participants’ harm rankings and their classification in the official US system.

Figure. Perceived harm rating of selected drugs on the seven risk factors. The shade intensity reflects the rank of the drug according to the US Controlled Substance Act. The darkest shade indicates Schedule 1 drugs (i.e., drugs that have highest potential for abuse and not allowed to be used even for medical treatment, such as ecstasy). The next lighter shade refers to Schedule 2 drugs (i.e., drugs that have high potential for abuse, but allowed under medical supervision with severe restrictions such as cocaine). Further lighter shade means Schedule 3 drugs (i.e., drugs that may lead to moderate or low physical dependence and have a less potential to abuse compared to the drugs from Schedule 1 and 2, such as, ketamine). The lightest shade means drugs of Schedule 4 (i.e., low potential for abuse that may lead to limited physical or psychological dependence, such as benzodiazepines). Not shaded date points mean unclassified drugs (e.g., alcohol). Click image to enlarge.

Limitations

- The data were collected through Internet surveys. This means that there is no way to guarantee the uniqueness of responses. It is also not clear if self-selected drug users who are also the Internet users appropriately represent the whole population of drug users.

- The number of participants who rated drugs varied by drug, so the stability of drug-related outcomes might vary by drug.

- The study is based on self-reported drug usage, and not verified by medical records or any physiological tests.

Conclusion

The study found no relationship between official drug classifications and users’ perceptions of drug harms. This could imply that formal drug classification does not reflect the actual harms and benefits of certain drugs. Alternatively, it might suggest that public health information has not been sufficient to give regular drug users appropriate knowledge about the actual harms and benefits of the substances they use. It also might be that both ranking systems do not accurately reflect drug use harms. Although it is unclear whether it is important that drug users’ perceptions of harms and benefits agree with the official classification, if consistency is valuable to reducing drug-related harms, it implies that the policy makers, scientists and educators should work together to reduce the gap between the official drugs classification and common perceptions of drug harm.

– Julia Braverman

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

References

Morgan, C. J. A., Noronha, L.A., Muetzelfeldt, M., Fielding A., & Curran, H. V. (2013) Harms and benefits associated with psychoactive drugs: findings of an international survey of active drug users. Psychopharmacology, 27(6), 497 -506

Fisher B., & Kendal, P. (2011) Nutt et al’s harm scales for drugs – Room for improvement but better policy based on science with limitation than no science at all. Addiction, 106, 1891 – 1892

________________

[1] Researchers also asked about benefits of drugs, however, this data is not presented here.