Alcohol misuse can certainly tarnish a romance. But for many couples, research suggests that drinking together is associated with building intimacy and relationship satisfaction (Homish & Leonard, 2005; Levitt & Cooper, 2010). This research suggests the existence of a motivational feedback loop: couples might expect to experience positive effects from drinking together, and so drink together. Then, drinking together might reinforce beliefs about alcohol and relationship intimacy. This week’s DRAM reviews a study that tested the motivational feedback loop hypothesis by studying couples over their first 9 years of marriage (Levitt & Leonard, 2012).

Methods

- The present study analyzed a subsample of 470 couples from the Adult Development Study, which administered surveys about alcohol intake and marital functioning to couples in Buffalo, New York over the first 9 years of marriage at 6 separate waves.

- Some of the measures completed at each wave included:

- Alcohol consumption (i.e., typical quantity of the single most common type of alcoholic drink that each individual consumed).

- Relationship-specific alcohol expectancies: Participants rated their expectancies for the effects of alcohol from four different domains when drinking in the presence of their partner. The sample items from each domain that follow are preceded by the stem, “how likely is it that alcohol will affect you so that you…”

- Intimacy/openness (“feel closer to your partner?”)

- Social/fun (“become happy and talkative with your partner?”)

- Sex enhancement (“become a better lover with your partner?”)

- Power/assertiveness (“feel confident, powerful, or in control with your partner?”)

- Frequency of relationship-drinking contexts: On an 8-point scale from not at all during the past year to every day or nearly every day, participants rated how often they drank in three different contexts: with their partner when both were drinking, with their partner when the partner was not drinking, and drinking apart from their partner.

- At each wave, researchers used relationship-specific alcohol expectancies from the previous wave to predict the frequency with which couples drank in each of the three relationship-drinking contexts. Researchers also used frequency of relationship-drinking contexts to predict relationship-specific alcohol expectancies in the following wave.

- Researchers differentiated between actor reports (i.e. reports provided by a given spouse), and partner reports (i.e. reports provided by the other spouse).

Results

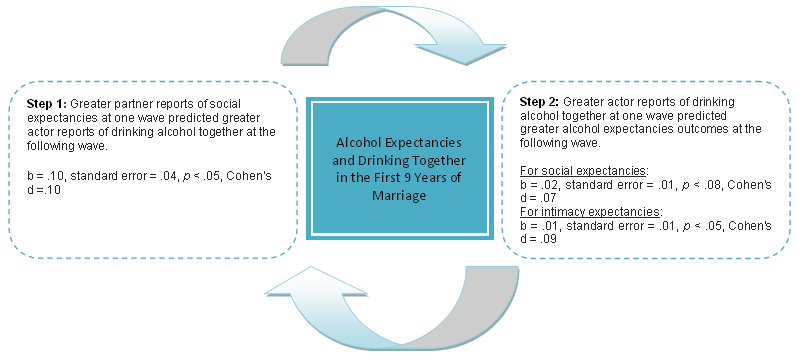

- The Figure illustrates some key results:

- Consistent with the motivational feedback loop hypothesis, greater partner reports of social expectancies at one wave predicted greater actor reports of drinking together at the next wave.

- Also consistent with the motivational feedback loop hypothesis, actor reports of drinking together predicted greater partner intimacy and social alcohol expectancies at the following wave.

- However, drinking together at one wave predicted less power expectancies from alcohol at the next wave. In other words, those couples who drank together often at one wave were less likely to expect alcohol to alter the power dynamic in the relationship for the next wave. Furthermore, for those with higher power expectancies, couples were more likely to drink apart at the next wave.

Figure. Motivational Feedback Loop (adapted from Leonard & Levitt, 2012). Note: b=the unstandardized coefficient. Click image to enlarge.

Limitations

- The measure of alcohol expectancies did not assess the expectancies individuals had for alcohol to have certain effects on their partner, expectancies that might influence their drinking within the relationship.

- This study used participants from a major urban region within New York, and it is therefore uncertain whether results can be generalized to couples from rural and suburban regions.

- Many of the associations, though significant and occurring one after the other (establishing a temporal criterion for causality), were very small. Their strength is therefore limited, so meaningfulness is questionable. However, in the context of relationships, small effects might grow to become large effects throughout the years.

Conclusions

The results of this study suggest that there are reciprocal effects between relationship-specific alcohol expectancies and the frequency of drinking together. In general, drinking together and positive expectancies about the effects of alcohol on the relationship are linked. However, when those expectancies involve imbalance in the relationship (i.e., power over one’s partner), they appear to facilitate drinking apart, not together. This suggests that drinking together is more likely to be perceived as having the potential to impact the relationship positively rather than negatively. Drinking is an important component in a relationship for many couples, who may use alcohol as a tool for greater relationship satisfaction. This study has important implications for understanding the complex relationship between drinking and relationship functioning.

–Melanie Mitchell

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

References

Homish, G.G., & Leonard, K. E. (2005). Marital quality and congruent drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 66, 488-496.

Levitt, A., & Cooper, M. L. (2010). Daily use and romantic relationship functioning: Evidence of bidirectional, gender-, and context-specific effects. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36, 1706-1722. doi: 10.1177/0146167210388420.

Levitt, A., & Leonard, K. E. (2012). Relationship-specific alcohol expectancies and relationship-drinking contexts: Reciprocal influence and gender-specific effects over the first 9 years of marriage. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. doi: 10.1037/a0030821