Research suggests that some people

might develop addictive behavior through their attempts to escape or avoid

experiences associated with stressful life events (Blaszczynski & Nower, 2002; Cooper, Frone, Russell, & Mudar, 1995).

Other contributing factors to developing addictive behavior include proximity

to and accessibility of potential objects of addiction (Cox, Yu, Afifi, & Ladouceur, 2005; Shaffer et al., 2004). This

week’s WAGER reviews a study that examined how these factors intersect and relate to gambling motivation,

frequency and gambling-related problems (Thomas,

Allen, Phillips, & Karantzas, 2011).

Methods

- Three hundred forty seven (229 females) current

gamblers who use electronic gambling machines (EGM) recruited through flyers in

various public message boards participated in the study. - Participants completed a survey regarding their

demographic information and frequency of EGM gambling. - Participants also reported whether they experienced stress

(defined as a major life change or loss) since commencing EGM and whether they

ever escaped from their problems by using behavior such as drinking alcohol, using

drugs or eating (0: never to 4: a lot of time) (i.e., general avoidance

coping). - Next, participants completed the following measures:

- The EGM motivation scale (Thomas, Allen,

& Phillips, 2009) , which consists of three subscales assessing avoidance

(e.g., Gambling provides a break from

worrying), accessibility (e.g., Venues

are close) and social (e.g., I can

meet new people) motivation. Response options ranged from 0 (Doesn't apply to me) to 5 (Applies to me almost always). - Problem gambling severity index (Ferris

& Wynne, 2001) – e.g., Have

you bet more than you could really afford to lose? Response options ranged

from 0 (Never) to 3 (Almost always).

- The EGM motivation scale (Thomas, Allen,

Results

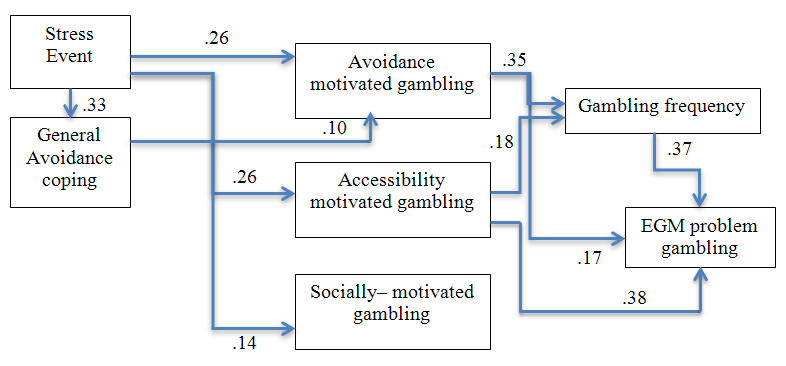

- Figure 1 depicts

significant (p < .05)

correlations among measured variables. Specifically,- Self-reported stress

correlated with all three types of gambling motivation. - Self-reported stress

related to general avoidance coping, which in turn related to

avoidance-motivated gambling. - Those who reported

stronger avoidance and accessibility motives for gambling reported having

more gambling-related problems and playing electronic gambling machines

more frequently.

- Self-reported stress

Figure 1: The

relationships among stress, avoidance coping, gambling motivations, frequency

and problems.

Limitations

- This is a correlational study; therefore, we cannot conclude if avoidance

motivation leads to gambling frequency and problems or vice versa, or if a

third variable is related to both factors. - Measures have the usual limitations of self-report

and therefore may not accurately reflect individual’s situational stressors,

motivations, and actual gambling behavior.

Conclusion

The results revealed that experiencing a stressful life

event was positively related to avoidance, accessibility, and social motives

for gambling. However, only avoidance and accessibility motives for gambling

were related to frequency of gambling and gambling-related problems; social

motivation did not relate to gambling related problems. This implies that to

predict how stressful life events relate to potential future gambling-related

problems, it is important to understand typical gambling motivations. The

results also demonstrated that the tendency to escape from problems using drugs

and alcohol is related to avoidance-motivated gambling, which is in turn

related to gambling frequency and problems. This supports the view of problem gambling

as a phenomenon that shares common antecedents with other expressions of addiction

(Shaffer, et al., 2004). Future research designs

that include experimental manipulations (e.g., of stress or gambling

motivation) might shed light on causal mechanisms.

-Julia Braverman

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide

feedback on this article.

References

Blaszczynski, A., & Nower, L. (2002). A pathways

model of problem and pathological gambling. Addiction,

97(5), 487-499.

Cooper, M. L., Frone, M. R., Russell, M., & Mudar,

P. (1995). Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational

model of alcohol use. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 69(5), 990-1005.

Cox, B. J., Yu, N., Afifi, T. O., & Ladouceur, R.

(2005). A National Survey of Gambling Problems in Canada. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry / La Revue canadienne de

psychiatrie, 50(4), 213-217.

Ferris, J., & Wynne, H. J. (2001). The Canadian Problem Gambling Index: Final

report.

Shaffer, H. J., LaPlante, D. A., LaBrie, R. A.,

Kidman, R. C., Donato, A. N., & Stanton, M. V. (2004). Toward a syndrome

model of addiction: Multiple expressions, common etiology. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 12, 367-374.

Thomas, A. C., Allen, F. C., & Phillips, J.

(2009). Electronic gaming machine gambling: Measuring motivation. Journal of Gambling Studies, 25(3),

343-355.

Thomas, A. C., Allen, F. L., Phillips, J., &

Karantzas, G. (2011). Gaming machine addiction: The role of avoidance,

accessibility and social support. Psychology

of Addictive Behaviors, 25(4), 738-744.

Terry McCarthy February 6, 2013

My small band of compulsive gamblers each reveal that their gambling was different from others from a very young age. One man claims that his compulsion started at age 8, with a raffle at an ice cream social. It got out of the control later and most eventualy were escaping something, but the difference between themselves and others was noted at a very young age. They each started recreationally and escalated later, and only began using gambling as an escape after the compulsion arose.