Starting college is a stressful and exciting time, full of new responsibilities and new experiences. For many, this includes experimentation with cigarettes. Studies have shown that individuals who suffer from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) are at higher risk for smoking. However, researchers have not studied the interaction between PTSD and smoking among college students during their first year at school. This issue of ASHES reviews an examination of how smoking rates among a freshman class population relate to experiences of PTSD symptoms (Read, Wardell, Vermont, Colder, Ouimette, & White, 2012).

Methods

Read et al. (2012) recruited 346 student smokers from two U.S. east coast universities.

- Each participant completed six surveys during the year: a baseline assessment during September, T1, and the remaining surveys once a month for the first semester and every other month during the second semester.

- For each assessment, the participants reported how often they had smoked during the previous 30 days and the typical quantity of cigarettes they smoked.

The researchers measured the presence of PTSD symptoms using the Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire (TLEQ©; Kubany et al., 2000)[1] and PTSD Checklist (Civilian Version; PCL–C; Weathers, Huska, & Keane, 1991; Weathers, Litz, Herman,Huska, & Keane, 1993)[2] at T1. Later, they analyzed the smoking trajectories of the students with respect to their PTSD “symptom status.”

- PTSD symptom status from the PTSD Checklist included: No PTSD Symptoms; Partial PTSD (students who met Criterion A and at least one above-threshold symptom in each B, C, and D); and Full PTSD (students who met Criterion A and one or more B symptoms, three or more C symptoms, and two or more D symptoms.)

The statistical analyses controlled for trait negative affectivity (i.e., a “unique influence” of PTSD), as indicated by the Neuroticism subscale of the Big Five Inventory (BFI; John & Srivastava, 1999)[3].

Results

- Students starting college who reported having undergone trauma or experiencing PTSD symptoms evidenced higher smoking rates initially (F(2.955)= 6.02, p<.01).

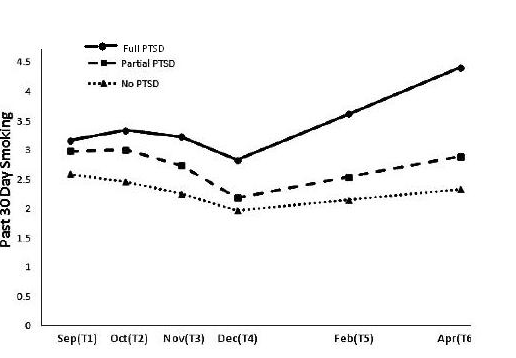

- During the first semester, smoking rates decreased for all PTSD status groups (See Figure 1); however, during the second semester (i.e., after winter break, which was predicted to be a significant stressor), those who had Full PTSD symptoms were at greater risk for a re-escalation of smoking compared to the No PTSD group (B=0.30, SE = 0.15, p=.039, 95% CI [.02, .59]).

- The Partial PTSD and No PTSD group did not differ in their likelihood of re-escalation during the second semester (B=0.08, SE = 0.13, p=.520, 95% CI [0.17, 0.34).

Figure. Means for past 30 days of smoking across the first year of college for the three symptom statuses. Click image to enlarge.

Limitations

- This study did not take into account the possibility of new traumas or changes in PTSD symptoms during the course of the study.

- This study also failed to examine the initial reason for the students to start smoking to see whether a trauma or something unrelated was a catalyst.

- This experiment was conducted at 2 midsize public universities on the east coast (one in the north and one in the south); consequently, The results obtained from this sample might not be generalizable to other college students.

- There was no independent confirmation of smoking behaviors beyond self-report.

- Self-reported data might exaggerate or minimize behaviors due to social desirability bias/stigmas.

Discussion

The results of this study suggest that individuals suffering from PTSD are more vulnerable to elevated smoking rates. Anxiety and stress are generally linked to smoking behaviors, even among those without a trauma history. Therefore, it is not surprising that the compounded strain of managing PTSD symptoms and starting college increases the likelihood of smoking. Targeting these mediating and moderating influence could lead to the development of prevention interventions that can be applied to the population at large and not just those who have suffered trauma. The transition to college is a difficult and anxious time for many, so if schools could reach out to those using cigarettes to help with their psychological or emotional distress –regardless how “serious” this distress — the potential benefits would be threefold:

- Targeted intervention could pre-emptively help students matriculating with PTSD overcome the difficulties they are experiencing before they turn to cigarettes.

- Early intervention would help to prevent “casual smoking” from becoming a serious habit.

- Early intervention would help to prevent the adverse health consequences that are commonly associated with anxiety, stress, and trauma.

– Emily Shoov

References

John, O. P., & Srivastava, S. (1999). The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality (2nd ed., pp.102–138). New York, NY: Guilford.

Kubany, E. S., Haynes, S. Y., Leisen, M. B., Owens, J. A., Kaplan, A. S.,Watson, S. B., & Burns, K. (2000). Development and preliminary validation of a brief broad-spectrum measure of trauma exposure: TheTraumatic Life Events Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment, 12, 210–224. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.12.2.210

Read, J. P., Wardell, J. D., Vermont, L. N., Colder, C. R., Ouimette, P., & White, J. (2012, August 13). Transition and Change: Prospective Effects of Posttraumatic Stress on Smoking Trajectories in the First Year of College. Health Psychology. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1037/a0029085

Weathers, F. W., Huska, J. A., & Keane, T. M. (1991). The PTSD Checklist—Civilian Version (PCL–C). Available from F. W. Weathers,National Center for PTSD, Boston VAMC, 150 S. Huntington Ave., Boston, MA 02130.

Weathers, F. W., Litz, B. T., Herman, D. S., Huska, J. A., & Keane, T. M. (1993, October). The PTSD Checklist (PCL): Reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. Paper presented at the meeting of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, San Antonio, TX.

________________

[1] A self-report questionnaire that assesses a range of traumatic experiences consistent with the DSM–IV–TR definition: “exposure to a traumatic event accompanied by fear, helplessness, or horror.”

[2] Evaluates for the DSM criteria including Criterion A (DSM definition of Trauma) and three additional clusters of symptoms: B (re-experiencing), C (avoidance/numbing), and D (arousal).

[3] A self-report measure assessing 5 elements of personality: Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism