According to the NIAAA (2012a), four out of five college students drink alcohol, and two out of five report binge drinking. Binge drinking is excessive drinking within about a 2 hour timeframe resulting in a BAC level of at least 0.08g/dL (NIAAA, 2012b). Researchers, however, often use a different definition of binge drinking: 5 drinks for men or 4 drinks for women consumed on one occasion (Wechsler, Davenport, Dowdall, Moeykens, & Castillo, 1994). Importantly, it is unknown how college students define binge drinking. This week, the DRAM reviews a study that assessed college students’ current definitions and understanding of binge drinking (Bonar, Young, Hoffman, Gumber, Cummings, Havlick, & Rosenberg, 2012).

Methods

- 424 undergraduates (299 women, 125 men) at a large state university responded to an email containing a survey and questionnaire.

- The Binge Drinking Definition Survey (BDDS) consisted of four closed and two open-ended questions:

- The two open-ended questions asked students to define a binge and provide the rationale for their definition. Researchers coded these answers based upon previous research;

- The four closed questions asked participants to indicate how many beers, shots, glasses of wine, and servings of combined alcohol types constituted a binge.

- The researchers also assessed demographics and drinking history, including frequency, quantity, and alcohol-related problems. To evaluate whether the mean number of drinks students thought comprised binge drinking varied with gender, alcohol type, and number of binges (i.e., 5+/4+ drinks on one occasion) in the past two weeks, researchers used a mixed model ANOVA.

Results

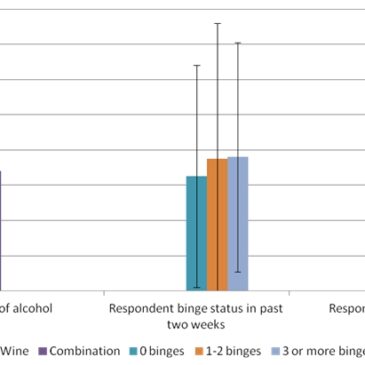

- The number of drinks that participants thought was needed for a binge varied by the type of alcohol, as well as the gender and drinking status of the participant (see Figure).

- Participants thought more beers were needed for a binge than shots, glasses of wine, or other combinations of alcohol, F(3,403) = 75.5, p < .001.

- Students who binged less frequently during the past two weeks reported that fewer drinks were necessary to comprise a binge than students who binged more frequently, F(2, 403) = 3.3, p < .05,

- Male students reported more drinks necessary to comprise a binge than did female students, F(1,403) = 6.6, p < .05.

- About a quarter of students (23%) referred to specific drinking motivations in their free response definitions of binge drinking (e.g., “drinking to forget…” – Bonar et al. 2012, p. 192).

Figure. Mean number of drinks participants thought comprised binge drinking based on types of alcohol, their past two week binge status, and their gender (adapted from Bonar et al., 2012). Note. Error bars represent standard deviations. Click image to enlarge.

Limitations

- The sample was recruited from a single university so it might not be representative of all college students in the US.

- Drinking history information was based on self- report so it might be subject to self-report biases.

Discussion

This study highlights the importance of considering student perceptions when attempting to design effective alcohol education and prevention programs in colleges. For example, some students incorrectly assumed that more beers were required for a binge than other alcohol types, suggesting the importance of educating college students about the equivalencies of different types of alcohol and about the alcohol content in each standard drink. Participants in this sample also highlighted drinking motivation as an important component of binge drinking. Though researchers’ definitions of binge drinking do not include motivation, students are correct to highlight its importance. For example, people who drink to cope with emotional problems tend to have more drinking problems than their counterparts absent such motivation. Therefore, prevention programs might be well-served by addressing the negative motivations for drinking among students and providing alternate coping mechanisms.

-Elisha Thapa

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

References

Bonar, E. B., Young, K. M., Hoffmann, E., Gumber, S., Cummings, J. P., Pavlick, M., & Rosenberg, H. (2012) Quantitative and Qualitative Assessment of University Students’ Definitions of Binge Drinking. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 26 (2), 187-193. doi: 10.1037/a0026440

Wechsler, H., Davenport, A., Dowdall, G., Moeykens, B., & Castillo, S. (1994). Health and behavioral consequences of binge drinking in college: A national survey of students at 140 campuses. The journal of the American Medical Association, 272, 1672-1677. doi:10.1001/jama.272.21.1672

National institute on alcohol abuse and alcoholism (NIAAA). (2012a). College drinking. Retrieved July 03, 2012, from http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/CollegeFactSheet/CollegeFactSheet.pdf

National institute on alcohol abuse and alcoholism (NIAAA). (2012b). Moderate & binge drinking. Retrieved July 03, 2012, from http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking