Children who experience corporal punishment are at higher risk for later aggression, delinquency, and overall poor mental health, including substance abuse/dependence (e.g., Gershoff, 2002; MacMillan, Boyle, Wong, Duku, Fleming & Walsh, 1999). However, due to measurement issues, it is unclear whether these associations are found outside the context of extreme childhood maltreatment (Baumrind, Larzelere, & Cowan, 2002). This week’s STASH reviews a nationally representative survey investigating the associations between childhood physical punishment in the absence of extreme maltreatment and a range of adult mental health conditions, including drug and alcohol use disorders (Afifi, Mota, Dasiewicz, MacMillan & Sareen, 2012).

Method

- Participants were 34,653 adults (age ≥20) who responded to the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC: Grant et al., 2005). The data were collected between 2004 and 2005.

- Participants answered questions about their demographics, childhood experience, mental health, and other topics.

- The physical punishment question was, “As a child, how often were you ever pushed, grabbed, shoved, slapped or hit by your parents or any adult living in your house?” Responses options ranged from “never” to “very often.”

- Afifi and colleagues classified participants as having experienced harsh physical punishment if they responded “sometimes,” “fairly often,” or “very often”.

- To distinguish between physical punishment and extreme childhood maltreatment, Afifi and colleagues excluded participants who reported experiencing severe child maltreatment (e.g., severe physical abuse, sexual or emotional abuse).

- The NESARC researchers assessed lifetime Axis I and Axis II mental health conditions, including alcohol abuse/dependence and drug abuse/dependence, using a fully structured clinical interview

- Afifi and colleagues conducted logistic regression to examine if reports of physical punishment were associated with lifetime Axis I and Axis II disorders. They included gender, age, marital status, race/ethnicity, education, income, and history of family dysfunction1as covariates in the model presented here. Those who experienced no physical punishment served as the reference group.

Results

- Six percent of participants (N = 1,258) reported experiencing physical punishment without more extreme childhood maltreatment. The remaining 19,349 experienced no physical punishment.2

- Of these 20,607 total respondents, 5,976 (29%) had a lifetime diagnosis of alcohol abuse/dependence and 1,518 (7%) had a lifetime diagnosis of any drug abuse/ dependence.

- Compared to those who did not report experiencing physical punishment, those who reported experiencing physical punishment as children were more likely to report experiencing later alcohol abuse/dependence (odds ratio = 1.59, 99.9%; confidence interval = 1.21 – 2.08, p ≤ 0.001) and later drug abuse/dependence (odds ratio = 1.53, 99.9% confidence interval = 1.06-2.20, p ≤ 0.001).

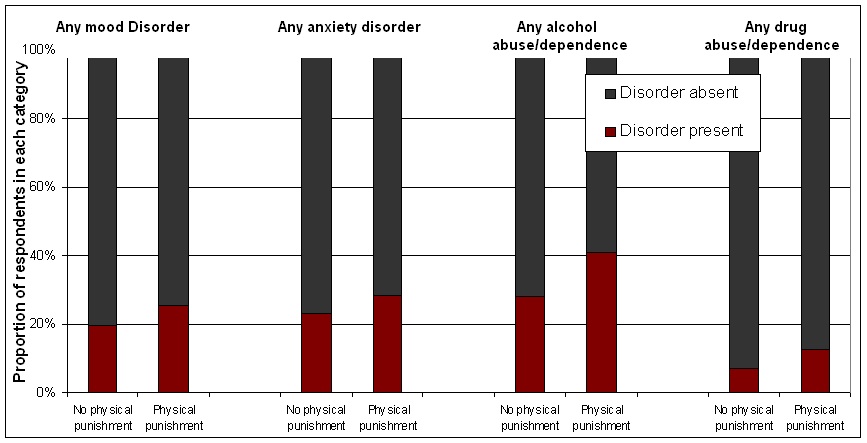

- Figure 1 presents the proportion of respondents in each group with lifetime diagnoses of any mood disorder, any anxiety disorder, any alcohol abuse/dependence, and any drug use/dependence:

Figure. Proportion of respondents in physical punishment and no physical punishment group. Click image to enlarge.

Limitations

- The wording of the question that assessed physical punishment does not include punishment; it rather refers to “being pushed, grabbed or hit” in general. It is not clear if respondents interpreted the question as related to punishment exclusively.

- This is a retrospective study that assessed punishment by self-report memories, which might be faulty or biased.

- Because this study used a correlational design, conclusions about causality remain speculative.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that harsh physical punishment experienced as a child, even in the absence of extreme maltreatment, is associated with alcohol and drug dependence/abuse later in life, as well as other mental health conditions. These findings inform parents as well as health care providers who give recommendation to parents about physical punishment. Future studies are necessary to examine the prospective association between physical punishment and these conditions, including potential underlying mechanisms such as chronic stress and the often-resulting physiological and emotional dysregulation that can result from such stress. While interpreting these results, the reader should take note that this study examined physical punishment that includes physical force more harsh than “customary” physical punishment (i.e., spanking).

-Julia Braverman

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

References

Afifi T. O, Mota N. P, Dasiewicz P., Macmillan H.L., Sareen J. (2012) Physical Punishment and Mental Disorders: Results From a Nationally Representative US Sample. Pediatrics 130, 1 -8

Baumrind, D. L., Cowan, R. E. & Phili, A. (2002) Ordinary physical punishment: Is it harmful? Psychological Bulletin, 128, 580-589.

Gershoff E.T. (2002) Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviours and experiences:a meta-analytic and theretical review. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 539-579.

Grant B. F, Hasin D. S, Stinson F. S, Dawson, D.A., June Ruan W, Goldstein R. B, Smith S. M, Saha T. D, Huang B. (2005) Prevalence, correlates, co-morbidity, and comparative disability of DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder in the USA: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychological Medicine. 35, 1747–1759

MacMillan, H. L., Boyle, M. H., Wong, M. Y., Duku, E. K., Fleming, J. E., & Walsh, C. A. (1999). Slapping and spanking in childhood and its association with lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders in a general population sample. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal, 161, 805-809.

________________

[1] Family dysfunction is defined as whether a parent or other adult in the household had 1 or more of the following: (1) had a problem with alcohol or drugs; (2) went to jail or prison; (3) was treated or hospitalized for a mental illness; (4) attempted suicide; and/or (5) died by suicide.

[2] The numbers do not sum up into the overall sample size, because they include only responders to the specific questions and exclude those who experienced severe physical, sexual or emotional childhood maltreatment.

Trish Wright July 18, 2012

I do not understand these conclusions. If I read this correctly, the researchers conclude children who were spanked “sometimes” were at higher risk for substance abuse than children who were never spanked. Hoever your article says the people who were answering the survey weren’t asked about “punishment” but only acts of physical aggression towards them. So why then does the opening sentence make a conclusion about “punishment”. I don’t see where this is warranted. I think this is an interesting research question and I look forward to more accurate research about it.

Julia Braverman July 27, 2012

Thank you for your interest in this post. The authors framed the article as investigating physical punishment. However, I agree with you that the actual question asked was not about punishment, but rather about any “hitting”. Some people may interpret “hit” as simple spanking, whereas other people may interpet it as severe physical aggression not necessary related to punishment. In any case, the wording is not clear. Therefore, we added the first limitation and encourage to interpret the results with caution.