Although research has shown a decline in the number of people smoking cigarettes in the United States, the annual premature death rate associated with smoking (440,000+) remains a cause for concern (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services). One potential strategy for promoting smoking cessation is to provide many readily accessible options for smokers who wish to quit. This week, ASHES reports on a study that tested the efficacy of a smoking cessation program delivered via video messages for cellular phones (cell phone) (Whittaker et al., 2011).

Methods

- The researchers recruited participants using radio, Internet, cell phone, magazine, newspaper, and media release advertisements in New Zealand.

- Eligibility: Participants had to be 16 years or older, smoke every day, have a desire to quit smoking, and have a cell phone that could receive video messages.

- After selecting a quit date, the researchers randomly assigned participants to an intervention or control group: each received mobile messages1 for 6 months.

- Control group – This group received one general health video message every 2 weeks.

- Intervention group – This group received a tailored set of video messages, text messages, other video messages (e.g., “truth” campaign), and on-demand support via texting key words (e.g., crave, stress, drinking) and a website. The tailored set included more options and contact (e.g., the ability to select and change role model, chronological schedule of messages – 1 video and text message/day for 1 week prior to quit date, 3 video and text messages/day on quit date, 3 video and text messages/day for 4 weeks following quit date, 1 message or other video every 2 days for the next 2 weeks, and then 1 message or other video every 4 days for the rest of the study).

- The researchers compared past week abstinence rates at 4 weeks, 12 weeks, and 6 months among the control and intervention groups.

Results

- 868 people registered to participate in the study; 642 people were ineligible, withdrew from the study, or did not complete a baseline interview; leaving 226 participants (control group n=116 and intervention group n=110).

- Control group completion rates – 80.2% (n = 93) at 4 weeks, 75% (n = 87) at 12 weeks, and 77.6% (n = 90) at 6 months.

- Intervention group completion rates – 73.6% (n = 81) at 4 weeks, 71.8% (n = 79) at 12 weeks, and 68.2% (n = 75) at 6 months.

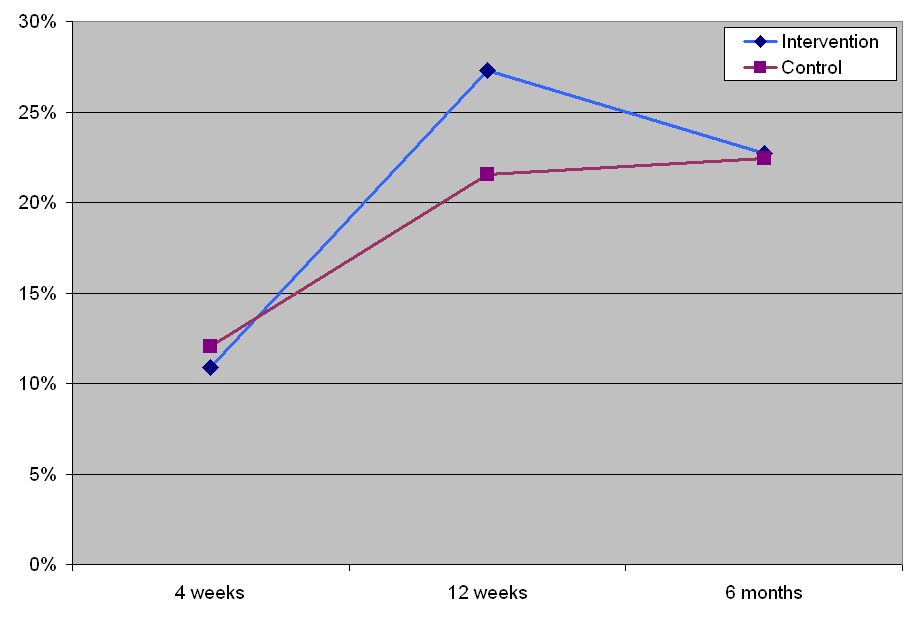

- Figure 1 illustrates abstinence rates over the course of the study for controls and the intervention group. The groups’ abstinence rates differed the most at 12 weeks, but were very similar at 4 weeks and 6 months.

- The control and intervention groups failed to evidence statistically significant differences at these time points (P = 0.8 at 4 weeks, P = 0.3 at 12 weeks, and P = 0.99 at 6 months).

- Researchers assumed 35 participants in the intervention group and 26 participants in the control group who had missing data were not abstinent.

Figure. Past week abstinence rates during study. Click image to enlarge.

Limitations

- The researchers aimed to recruit a much larger sample. The low participation rate suggests that these results might not be generalizable to the New Zealand population or other populations.

- The researchers compare one type of video messaging intervention against a more complex type of video messaging intervention for smoking cessation. Without a “control” group of people who did not receive any video messages, it is difficult to determine whether either intervention system was effective or if people were quitting on their own.

Discussion

The results indicate that a more personalized smoking cessation video messaging system with additional resources was not more effective at helping people achieve abstinence than an automated video messaging system. It is unclear if this type of intervention is effective, and it is impossible to interpret these null findings. In this instance, it might be that the intervention was not successful, or that the selection of participants and low participation rate might be responsible or other methodological problems might be responsible for the absence of significant results.

However, video and text messaging intervention programs might hold promise because most people carry their cell phones with them at all times and this type of system could allow for intervention at any time and potentially when it is needed the most. Future research should test the efficacy of this type of intervention among different populations, age groups, and addictions (e.g., gambling, substance use, drinking).

–Tasha Chandler

References

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Tobacco prevention and control: New actions to end the tobacco epidemic Retrieved Jul. 13, 2011, from http://www.hhs.gov/tobaccocontrol/index.html

Whittaker, R., Dorey, E., Bramley, D., Bullen, C., Denny, S., Elley, R., . . . Salmon, P. (2011). A theory-based video messaging mobile phone intervention for smoking cassation: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 13(1), e10. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1553

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

________________

1The video messages were a diary of role models who shared their difficulties, techniques, and strategies for quitting.