In an ongoing series, we highlight celebrity substance abuse and its media portrayal. A previous Addiction and the Humanities investigated how the media used Michael Jackson’s death to highlight the broader issues associated with prescription drug abuse and its consequences. Today’s BASIS examines the public response to the death of Amy Winehouse, English singer-songwriter and jazz musician.

Amy Winehouse was found dead Saturday, July 23rd, in her London flat. She was only 27 years old. An autopsy proved inconclusive, and it will take two to four weeks before toxicology test results are available (Forbes, 2011). However, the media already has begun heralding her cause of death as a drug overdose. Her musical talent and youth add a heartbreaking quality to her death, which has reignited debates over the nature of addiction, its causes, and its treatment.

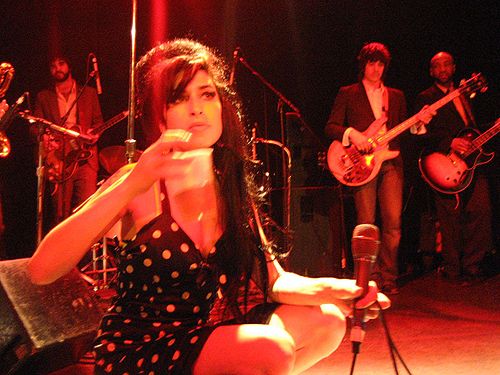

By daniel arnold (amy winehouse at bowery ballroom 18) [CC-BY-SA-2.0 (www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Drug user as dramatis personae

Winehouse spent most of her adult life in the public eye, often the butt of snarky tabloid jokes for her erratic behavior, destructive relationships, and strange performances. Figuring prominently among these more common celebrity gaffes, however, was her ever-present drug and alcohol abuse. She allegedly abused heroin, ecstasy, cocaine, and alcohol, and began smoking crack cocaine during a tumultuous marriage, which eventually ended in divorce (Telegraph, 2008).

One could argue that Winehouse’s behavior went beyond the usual celebrity drug use. It was not possible to separate her drug use from her public persona. Her addiction history showed up in everything from her last name, to her emaciated, heroin-chic sartorial style, to her music. The singer, who publicly acknowledged her drug and alcohol use, sang about her own demons in her hit single “Rehab.” The song cited a real plea by her friends and father to seek treatment, she said.

“They tried to make me go to rehab, I said ‘No, no, no’” (Winehouse, “Rehab”)

“Rehab,” which landed her the 2008 Grammy Awards for Song of the Year and Best Female Pop Vocal Performance, reinforced her identity as an eccentric artist who drank heavily and used drugs. Few things are as intriguing as a human train wreck – throughout history people seem to have enjoyed a public hanging – especially one so young and talented. It is likely that part of her success hinged on her ability to retain and promote this image. However, cultivating a tortured, eccentric persona is one thing; living out that persona is another. It is unclear to what extent maintaining her public image encouraged her self-injurious behavior. As is often the case for those who struggle with addiction, Winehouse reportedly had underlying psychosocial problems that might have worked together with her substance abuse to result in her distinct expression of addiction.

The cards were stacked

Depression and other psychiatric disorders create an increased risk of addiction, and the prevalence of psychopathology is increased among individuals who are dependent on multiple psychoactive substances (Shaffer & LaPlante, 2004). Before her death, Winehouse revealed that she struggled with an eating disorder and a diagnosis of manic depressive behavior, for which she was not taking prescription medication. “I do drink a lot. I think it’s symptomatic of my depression,” she said in an interview on a British TV show. “I’m manic depressive, I’m not an alcoholic, which sounds like an alcoholic in denial.” This admission on her part is consistent with the self-medication hypothesis of substance abuse (Shaffer, 1997), which states that people struggling to alleviate adverse mental, physical and emotional states will often turn to illicit substances to help them do this.

Should she have said “Yes, yes, yes?”

People often invoke Amy’s refusal to commit to a rehab program as the reason for her ongoing problems. It is at the very least unclear whether she would have improved rapidly, had she stayed in rehab against her will, or submitted to pressure from her family members. Coercion by the family or treatment provider often leads to aversion and ultimately abandonment of treatment. However, there are many instances where people are coerced into treatment and have very positive outcomes. We just can’t predict who will suffer or who will succeed from a coerced treatment.

The most robust and reliable predictor of positive treatment outcome is patient readiness to change (Shaffer, 1997). It is unclear whether Winehouse was at the stage where her readiness to change overcame her ambivalence. She did check herself into rehab programs, the latest being a treatment program at the Priory Clinic in London this spring. After spending a week in the program, she checked out June 2, 2011, saying she would continue outpatient treatment at the Priory Clinic. She continued on to a failed European tour where she stumbled around on stage, appeared to be in a drunken daze, and was booed offstage by disgruntled fans.

Perhaps she left treatment too soon. Central to the understanding of addiction as a physical ailment is the belief that some form of treatment or self-help must be ongoing to avoid relapse; however, research suggests that recovery from addiction without treatment is more common than previously expected (Albanese & Shaffer, 2003).

The public response

Within an hour of Winehouse’s death, social media websites saw their traffic skyrocket as countless people expressed their shock, anger, and sadness. Celebrities like Demi Moore, Rihanna, and Kim Kardashian among others expressed their condolences and sympathy with Winehouse’s family on Twitter. On the darker side, disturbing video footage of Winehouse’ last concert in her European tour hit the top of YouTube watch lists. Commenters remarked, sometimes cruelly, upon her drug-addled and bizarre behavior. Larger media sites suggested her addition to the “27 club”—a band of talented musicians who died at the age of 27 because of drug abuse, including Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, Kurt Cobain, and now, apparently, Winehouse.

All this activity illustrates the public’s complex attitudes towards drug use in general and celebrity drug use in particular. These attitudes are, in turn, layered on top of an old story about addiction and artists. Many artists suffer from bi-polar (aka manic depression), depression and other mental illnesses (Kaufman, 2000; Weisberg, 1994). Nevertheless, it is important to remember that only some abuse psychoactive substances. The myth that artists are predisposed to addiction is encouraged by the media, which is interested in generating sensationalism and often embellishes tragedy over talent. Winehouse’s celebrity status might adversely have influenced the course of her addiction, but not necessarily because she was an artist. First, her environment might have fostered her drug dependency. For celebrities, the negative media coverage that focuses on their addiction can trigger anxiety, self-destructive behavior, and ongoing substance abuse. Media outlets detail the challenges celebrities face; this is quite different from the average citizen, who usually only has to worry about those in their close-knit circle. Second, Winehouse had sufficient funds to avoid the heavy hand of the law – for the most part – and to feed her habits.

Public response to Amy Winehouse’s death might reflect broader attitudes and misunderstandings about addiction. People are both fascinated by, and condescending towards, people with addiction. When we know them personally, we mourn their pain and struggle to figure out why they repeatedly did things to hurt themselves. Failing to understand their repeated pattern of self-injury, observers pass judgment and stigmatize those with addiction. Celebrities with drug-related addiction are no exception to this pattern of passing judgment. The public sneers and berates celebrities failing so spectacularly when they have so much.

However, perhaps celebrities who open up discussion about addiction and rehab help take the stigma out of it for everyone else, whether by going through it or singing about it. It is possible that Amy and other celebrities—Rihanna and Eminem, who both address addiction and rehab in their music—can help to break down walls to addressing drug problems in the larger population.

A disease that will kill

Actor Russell Brand, who has firsthand knowledge about substance use, abuse, dependence and addiction, wrote a lengthy tribute to Winehouse on his blog (2011). In his tribute, he urged the media and the public to view addiction "not as a crime or a romantic affectation but as a disease that will kill." "We need to review the way society treats addicts, not as criminals but as sick people in need of care,” he pleaded. “We need to look at the way our government funds rehabilitation."

This change is possible. The movement toward treatment instead of criminality is being reflected in residency programs that seek to establish addiction medicine as a standard specialty along the lines of pediatrics, oncology or dermatology (Quenqua, 2011). Ten medical institutions have just introduced the first accredited residency programs for addiction medicine. Hope lies on the horizon for those suffering from a draining and sometimes deadly disorder.

Most importantly for Winehouse, we should remember her life, not as just another cautionary tale about substance abuse, but as a story about a living, breathing being who struggled with forces beyond her control and who died before it was her time; one whose impressive musical legacy hopefully will not be overshadowed by the public fascination with her painful history.

-Kat Belkin

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

References

ABC (2011). Amy Winehouse: Career shadowed by manic depression. ABC News Health. L. Salahi. Retrieved Jul. 26, 2011, from http://abcnews.go.com/Health/w_MindBodyNews/amy-winehouse-career-shadowed-addiction/story?id=14145112

Albanese, M. J., Shaffer, H.J. (2003). "Treatment considerations in patients with addictions." Primary Psychiatry 10(9): 55-60.

Brand, R. (2011). For Amy. Russell Brand. Retrieved Jul. 26, 2011, from http://www.russellbrand.tv/2011/07/for-amy/

CBS (2011). Amy Winehouse death sets Twitter on fire. Celebrity Circuit. Retrieved Jul. 26, 2011, from http://www.cbsnews.com/8301-31749_162-20082502-10391698.html

Forbes.com (2011). Family spokesman: Amy Winehouse's funeral Tuesday, Associated Press.

Kaufman, J. C. (2000). "The Tragic Muse: The Connection Between Mental Illness and Creativity." PsycCritiques 45(6).

Quenqua, D. (2011). Rethinking addiction's roots, and its treatment. New York Times. New York. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/07/11/health/11addictions.html

Shaffer, H. J. (1992). Psychology of stage change. Substance abuse: a comprehensive textbook J. H. L. P. R. R. B. M. J. G. Langrod. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins: 100-106.

Shaffer, H. J., LaPlante, D.A., LaBrie, R.A., Kidman, R.C., Donato, A.N., Stanton, M.V. (2004). "Toward a syndrome model of addiction: multiple expressions, common etiology." Harvard Review of Psychiatry 12: 367-374.

Telegraph (2008). Amy Winehouse bailed over drugs video. Celebrity News. A. Singh.

Weisberg, R. (1994). "Genius and madness: a quasi-experimental test of the hypothesis that manic depression increases creativity." Psychological Science 5(6): 361-367.

Winehouse, A. “Rehab”, Metro Lyrics. Retrieved Jul. 26, 2011, from http://www.metrolyrics.com/rehab-lyrics-amy-winehouse.html

Sue July 27, 2011

A very timely and thoughful Humatities addition. I am sure that the authoress (Kat — undaubtedly short for Catafalque) whould have made it shorter is she had more tiem.

Anne Fletcher, MS, RD July 27, 2011

Excellent article. I’m tired of the media and addiction professionals absolving addicted people of blame because they have a disease, then turning around and blaming them for “not accepting treatment” or doing what they’ve been “told to do”. And of course, everyone has ruled on the cause of death before it’s even known, when it’s been widely reported that Amy had multiple health and mental health problems that may have contributed to her death. Sadly, she may never have received quality evidence-based treatment because several of her rehab stays were at a facility that a judge said “would shame the Third World”(see below.) Another program she went to offered a very traditional model of treatment – Amy was anything but traditional! Perhaps the focus should have been more on her underlying disorders. Thanks for the balanced perspective on this.

(http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1343330/Causeway-Retreat–10k-week-celebrity-rehab-shames-Third-World.html#ixzz1TLaqRUKp)

Amy R Lockhert February 25, 2017

” recovery from addiction without treatment is more common than previously expected (Albanese & Shaffer, 2003).”

i don’t know that WITHOUT treatment is all correct here

i THINK there is something but it was not a traditional treatment IE rehab or medications

a Miracle and who what does miracles??

God