Research tells us that few people with gambling problems seek treatment (Shaffer & Martin, 2011). Perhaps people’s views of addiction, gambling in particular, create barriers that deter disordered gamblers from seeking formal treatment. This week The WAGER reviews a study of beliefs about gambling addiction (Cunningham, Cordingley, Hodgins, & Toneatto, 2011).

Methods

- Cunningham et al. conducted a random digit dialing telephone interview among adults residents living in Ontario (n=8,467) to:

- Assess their agreement with different views of gambling abuse (strongly agree to disagree): Gambling abuse is a disease or illness; a wrongdoing; a habit, not a disease; or an addiction similar to drug addiction.

- Assess agreement with different views of the ability to change gambling behavior (yes or no) – People with gambling problems can: fix it on their own without getting any treatment?; reduce their gambling to that of a social gambler or do they need to quit altogether?

- Report their current (past year) and lifetime gambling problems – Participants who spent more than $100 gambling during their lifetime were asked past year and lifetime NODS-CLiP questions; and if they endorsed one or more items, they also completed the NORC DSM Screen for Gambling Problems.

- The researchers used logistic regression analyses to identify significant predictors of participants’ perceptions of the levels of treatment and curbing use necessary to fix gambling problems.

Results

- Most participants (56%) strongly agreed that gambling abuse should be categorized as an addiction similar to drug addiction, followed by 38% as a disease or illness, 32% as a habit, not a disease, and 17% as a wrongdoing.

- 53% of participants felt that (a) treatment was needed to fix a gambling problem, and 71% felt that (b) people needed to remain abstinent to completely fix their gambling problem.

- 50.2% of participants (n = 4,250) reported spending less than $100 on gambling during their lifetime (i.e., non-gamblers). Of those who spent at least $100 (n = 4,217):

- 71.4% (n = 3,012) did not endorse experiencing any gambling problems according to NODS CliP (i.e., social gamblers).

- 28.6% (n = 1,205) endorsed one or more problem(s) and were assessed as possible or probable pathological gamblers (PG) by the NORC CLiP (i.e., possible PGs).

- Of those, 12.4% (n = 150) met criteria for lifetime PG and half (n = 75) also met criteria for past year PG by the NORC DSM Screen (i.e., PGs).

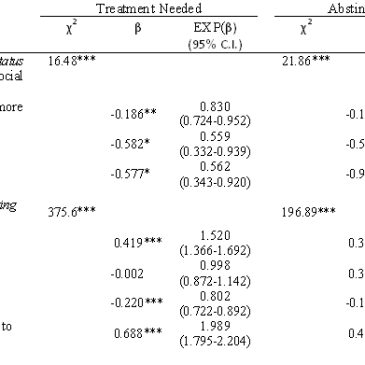

- As Table 1 shows:

- Compared to possible PGs and PGs, non-gamblers and social gamblers were significantly more likely to believe that treatment and abstinence were needed to completely fix a gambling problem.

- Those who strongly agreed that gambling problems are a disease, a habit or an addiction were significantly more likely to believe treatment was necessary to fix gambling problems. The disease and addiction groups and those who viewed disordered gambling as a wrongdoing were significantly more likely to believe that abstinence was necessary.

- Those who strongly agreed that disordered gambling was a habit were significantly less likely to believe treatment was necessary.

Table 1 – Logistic regression analyses of participants’ perceptions of gambling (adapted from Cunningham, et al., 2011)

* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001

Limitations

- This study uses retrospective self-report to identify both respondents with gambling disorders and the attitudes of those with disorders, and the reported attitudes and behaviors might not be credible (Baumeister, Vohs, & Funder, 2007).

- The results might not be generalizable to other adult populations, especially given the high prevalence rates for possible PG and PG among the participants.

Discussion

The results suggest that most possible PGs and PGs do not feel that treatment and abstinence are essential to recovering from gambling problems. This might relate to how they understand their problems with gambling and potentially be a barrier to treatment. However, those without gambling problems appear to believe that both treatment and abstinence are necessary for recovery. These findings are consistent with the fundamental attribution error (Ross, 1977): people think their behavior is the result of external influences (e.g., social pressure), but the behavior of others is due to internal states (e.g., mental illness).

Perhaps treatment providers can improve their programs by making it clear what treatment entails, educate the general public and potential treatment seekers about rational gambling beliefs, and also promote alternative treatment methods in an effort to dissipate the negative perceptions surrounding gambling addiction. Most of all, treatment providers might consider how to make treatment more attractive to all who might need it.

-Tasha Chandler

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

References

Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., & Funder, D. C. (2007). Psychology as the science of self-reports and finger movements: Whatever happened to actual behavior? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2(4), 396-403. doi: DOI: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00051.x

Cunningham, J. A., Cordingley, J., Hodgins, D. C., & Toneatto, T. (2011). Beliefs about gambling problems and recovery: Results from a general population telephone survey. Journal of Gambling Studies, Online first. doi: 10.1007/s10899-010-9231-z

Ross, L. (1977). The intuitive psychologist and his shortcomings: Distortions in the attribution process. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 10, pp. 173-220). New York: Academic Press.

Shaffer, H. J., & Martin, R. (2011). Disordered gambling: Etiology, trajectory, and clinical considerations. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 7, 483-510. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-040510-143928