It’s that time of the year again…March Madness. Next to the Super Bowl, this event stimulates the most sports wagering in the U.S. During 2004, the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) conducted a national survey of gambling and other high risk behaviors among college athletes, which is described in a number of publications or reports (Ellenbogen, Jacobs, Derevensky, Gupta, & Paskus, 2008; Huang, Jacobs, Derevensky, Gupta, & Paskus, 2007a, 2007b; Petr, Paskus, & Dunkle, 2004). This survey revealed that college athletes (especially males) evidenced sports betting despite the NCAA rules prohibiting student-athletes from wagering on college or professional sports. In response to these results, NCAA president, Myles Brand, commissioned a task force of key figures in college athletics and the gambling research/treatment community to examine the data and recommend a course of action. The resulting recommendations were wide ranging and included various forms of educational outreach. During 2008, the NCAA conducted a subsequent national study of student-athletes. Analyses of these data are underway and the NCAA plan to release an initial report about the study later this year. This week’s WAGER reviews some preliminary findings of the 2008 NCAA study (Paskus, Petr, Vicente, & Derevensky, 2009; Petr et al., 2004).

Methods

- Using a cluster or three-stage sampling design in both the 2004 and 2008 studies, researchers approached all 1000+ NCAA member colleges to participate through faculty athletics representatives. Each school was asked to survey all members of 1-3 teams selected by the NCAA through a stratified random sampling procedure, with the intent of providing samples representative of all sports and NCAA divisions.

- Participation was anonymous at both the student and school level. Based on the number of responses and experience with similar surveys, the NCAA estimated a school-level response rate of 60-65% for both 2004 and 2008. Investigators did not calculate the student-level or team response rate for either survey.

- Without the student or team response rate, we cannot calculate a study-wide response rate. However, because this rate emerges from a product of school, team and student response rates, we know that the study response rate is going to be < .60-.65.

- Rigorous data cleaning procedures were employed, including the use of item response theory (IRT) to enhance validity checks.

- To enhance comparability, investigators retroactively applied the 2008 data cleaning methods to the 2004 survey data and weighted both data sets to the NCAA’s estimate of the 2008 participation rates for 22 sports (11 male and 11 female).

- The 2008 survey contained a single item to assess sports betting prevalence and frequency among respondents, whereas the sports betting data for the 2004 survey was based on a composite of items in the survey.

- Researchers reanalyzed the 2004 data set and the modified 2004 results to make these comparable to the 2008 results.

- The 2004 sample included 19,354 student-athletes and the 2008 sample included 19,371 student-athletes.

- Both the 2004 and 2008 surveys included 10 questions based on the DSM-IV criteria for pathological gambling (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) to assess gambling status. Each affirmative answered was scored as 1 with the total score being a summation of scores for each item.

- Researchers classified respondents as social gamblers if they received a score between 0-2, at-risk gamblers if they received a score of 3 or 4 and probable pathological gamblers if they received a score of 5 or more.

Results

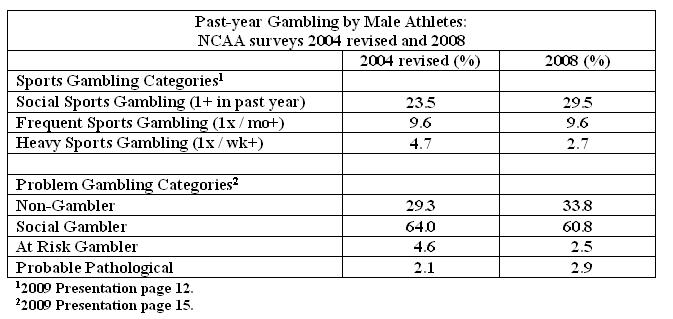

- As shown in Table 1, social levels of sports wagering (i.e., defined as having gambled on sports in the past year) appear to have increased from 2004 to 2008. Researchers reported that estimates of student-athletes gambling once per month or more was similar across the two cohorts and heavy sports gambling (i.e., once/week or more) decreased since 2004.

- Analysis of the gambling-type classification according to the DSM-based gambling screen indicates that the proportion of non-gamblers and social gamblers is similar across surveys. However, the 2008 survey reveals fewer at-risk gamblers and more probable pathological gamblers.

- Overall, the proportion of male athletes endorsing any number of gambling-related problems declined from 6.7% in 2004 to 5.4% in 2008.

Table 1: Past-Year Gambling by Male Athletes

Limitations

- This survey gathers self-reported data without corroboration; therefore, this study is subject to the problems commonly associated with self-report. For example, given the highly sensitive nature of the survey questions (e.g., sports gambling for college athletes is both illegal in nearly all states and violates NCAA policy), some participants might not have reported accurately their sports betting behaviors in spite of their anonymity.

- General cohort shifts for gambling behaviors among student-athletes and the difficulties matching interventions received to specific students hampers our ability to isolate the effect of the NCAA’s educational efforts.

- Differences in the 2004 and 2008 survey instruments might have confounded the observed change in the prevalence rates of gambling on sporting events.

- The researchers chose survey procedures designed to enhance anonymity; however, these procedures make it difficult to calculate a student-level survey response rate. The NCAA estimated school level response rate of 60% to 65% sets a ceiling for the overall response rate in a study that employs multiple stage sampling. The survey response rate is likely lower because it is obtained by multiplying the school-level response rate by the team level response rate by the student-level response rate. Low response rates are a cause for concern about the representativeness of survey data and our ability to generalize its findings.

- In this case, disregarding the team level response rate, a student-level response rate lower than 80% will yield a survey-level response rate less than 50%. According to Mangione (1995, pgs. 60-61), “response rates between 50% and 60% are barely acceptable and really need some additional information that contributes to confidence about the quality of your data. Response rates below 50% really are not scientifically acceptable.” Thus, absent a very high level of team and student-level response, there are not sufficient safeguards against sampling bias.

- In addition, because evidence has shown that athlete gambling rates vary by NCAA division (e.g., Nelson et al., 2007), it is important to determine whether response rates are similar across NCAA divisions . Any inconsistencies across these rates can lead to over or under estimates of student-related gambling activities.

Conclusion

Among male college student athletes, the subsequent 2008 NCAA study shows an increase in the number of sports gamblers, a decrease in at-risk gambling behavior and an increase in the number of participants classified as a probable pathological gamblers. It is possible that prevention initiatives developed and implemented by the NCAA task force might have contributed to the changes in some measures of male college athlete gambling; however, other factors also could be at play. Additional follow-up research is needed to have a better understanding of the effectiveness and impact of such intervention strategies.

In the meantime, the NCAA tournament will garner much attention and wagering. College students, both athletes and non-athletes, who choose to gamble, are best advised to exercise caution when wagering on the outcome.

-Erica Marshall

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). DSM-IV: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (Fourth ed.). Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association.

Ellenbogen, S., Jacobs, D., Derevensky, J., Gupta, R., & Paskus, T. (2008). Gambling behavior among college student-athletes. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 20(3), 349-362.

Huang, J., Jacobs, D., Derevensky, J., Gupta, R., & Paskus, T. (2007a). Gambling and health risk behaviors among U.S. college student-athletes: findings from a national study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 40(5), 390-397.

Huang, J., Jacobs, D., Derevensky, J., Gupta, R., & Paskus, T. (2007b). A national study on gambling among US college student-athletes. Journal of American College Health, 56(2), 93-99.

Mangione, T. W. (1995). Mail surveys: improving the quality (Vol. 40, Applied Social Research Methods Series). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Nelson, T., LaBrie, R., LaPlante, D., Stanton, M., Shaffer, H., & Wechsler, H. (2007). Sports betting and other gambling in athletes, fans, and other college students. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 78(4), 271-283.

Paskus, T., Petr, T., Vicente, R., & Derevensky, J. (2009). Results from the 2008 NCAA Study on Collegiate Wagering: The National Collegiate Athletic Association.

Petr, T., Paskus, T., & Dunkle, J. (2004). 2003 NCAA National Study on Collegiate Sports Wagering and Associated Behaviors: The National Collegiate Athletic Association.