Longitudinal studies have focused on adolescents’ impulsive activities and have found this to be a period during which youth explore and engage in gambling (Vitaro, Wanner, Ladouceur, Brendgen, & Tremblay, 2004; Wanner, Vitaro, Ladouceur, Brendgen, & Tremblay, 2006). However, very few longitudinal studies have focused on the gambling activities of young adults. This week, the WAGER reviews a study (Goudriaan, Slutske, Krull, & Sher, 2009) that examined clusters of gambling activities among college students over a four year period to examine whether there were changes in gambling behavior/participation over time.

Methods

- Incoming students from the University of Missouri-Columbia between the ages of 17.5 and 19.5 years old at baseline were recruited to participate in a longitudinal study during the summer prior to their freshman year.

- A subsequent online survey was administered to participants each spring semester.

- 3,720 students completed one or more surveys: year 1 (n=2450); year 2 (n=2482); year 3 (n=2357); and year 4 (n=2250).

- The survey measured participation in ten gambling activities each year: playing cards for money, betting on horses/dog/animal races, betting on sports, playing dice games, casino gambling, lottery, bingo, slot/poker/gambling machines, playing games of skill for money, and Internet gambling.

- The researchers used latent class analyses (LCAs) to derive gambling group membership defined by games played and stability of group membership over time.

Results

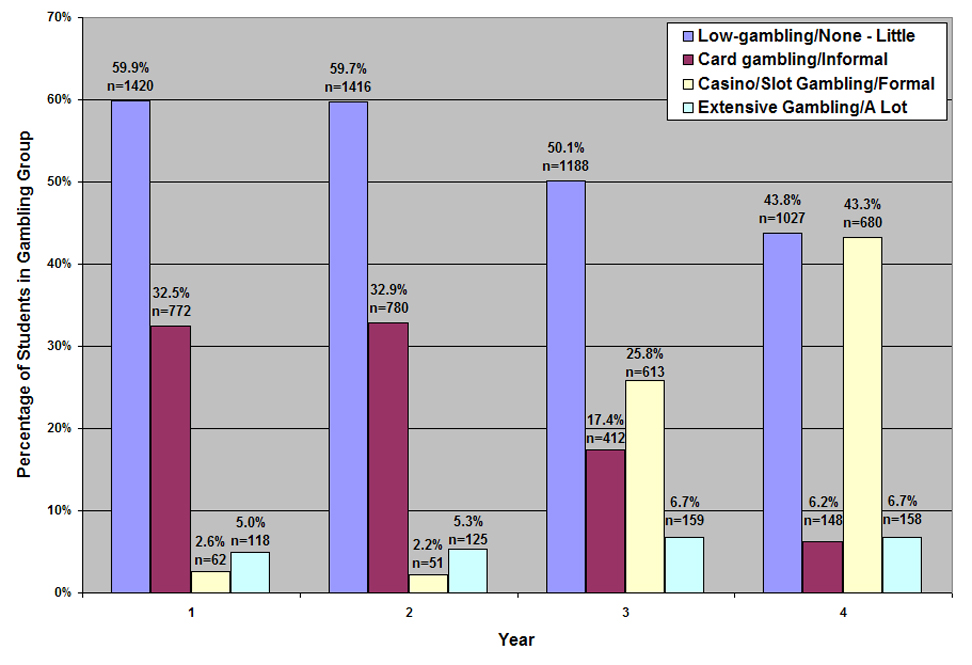

- LCAs identified four gambling groups: the low-gambling group gambled sporadically or not at all; the card gambling group included card, lottery, and non-regulated forms of gambling (e.g., sports betting and games of skill for money); the casino/slot gambling group engaged in more formal gambling (e.g., slot machine and casino); and the extensive gambling group engaged in all or most of the gambling activities.

- Table 1 shows the percentage of participants in each group at each year.

Figure 1: LCAs of Gambling Group Percentages each Year Including Number of Participants (adapted from Goudriaan et al., 2009).

Click image to enlarge, or adjust your browser's zoom setting.

Click image to enlarge, or adjust your browser's zoom setting.

*Please note that the figure encompasses students based on estimated frequencies including estimated data of students missing at one or more data collection points.

- Participants’ gambling activities changed over time. Transitions from group to group showed:

- The gambling groups did not significantly change during the first two years of the study; this is a time when most students are legally not allowed in casinos.

- A comparison of gambling behavior/participation between the second year and the fourth year yields many notable findings.

- Membership decreased by 26.6% (59.7% to 43.8%) among the low gambling group and increased by 20.9% (5.3% to 6.7%) within the extensive gambling group.

- Membership in the group that gambles in more formal venues (i.e., casino/slot gambling group) increased 94.9% (2.2% to 43.4%) – that is more than 13 times.

- Membership decreased by 81.2% (32.9% to 6.2%) within the card gambling group as membership within the casino/slot gambling group increased, indicating a transition in preference from non-regulated to formal gambling.

Limitations

- The results of this study might not generalize to all populations because the participants were recruited from a single-site and were predominantly white (90%).

- The gambling activities were ambiguous in terms of venue and activity. As a result, participants might have endorsed more than one activity for the same behavior (e.g., card gambling for money can happen with friends or in a casino).

Conclusion

This study’s findings indicate that gambling activities cluster into two main types among college students: non-regulated and formal. In addition, gambling preferences change between the first two years of college and the second two years of college; during this time, most college students become of legal age to enter and gamble in casino environments. According to these findings, this newfound gambling opportunity significantly impacts student gambling preference (i.e., non-regulated to formal gambling). Being cognizant of these preference shifts toward gambling activities among college students should help researchers design better intervention/education programs. This study suggests that a flexible intervention program that changes as a student progresses through college would be most appropriate. Perhaps colleges should emphasize gambling education focusing on non-regulated form of gambling for underclassmen and gambling education about formal forms of gambling for upperclassmen.

– Tasha Chandler

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

References

Goudriaan, A. E., Slutske, W. S., Krull, J. L., & Sher, K. J. (2009). Longitudinal patterns of gambling activities and associated risk factors in college students. Addiction, 104(7), 1219-1232.

Vitaro, F., Wanner, B., Ladouceur, R., Brendgen, M., & Tremblay, R. E. (2004). Trajectories of gambling during adolescence. Journal of Gambling Studies, 20(1), 47-69.

Wanner, B., Vitaro, F., Ladouceur, R., Brendgen, M., & Tremblay, R. E. (2006). Joint trajectories of gambling, alcohol and marijuana use during adolescence: A person- and variable-centered developmental approach. Addictive Behaviors, 31(4), 566-580.