Relapse is common for multiple paths of recovery from addiction (e.g., self-guided, treatment assisted, etc.). Various studies have shown that most expressions of addiction carry a significant chance of relapse. For instance, in one 2003 study, 50% of marijuana smokers fit the criteria for relapse (Moore & Budney, 2003). Two other 2005 studies found high relapse rates among those recovering from alcoholism (i.e., 82% of outpatients and 73% of inpatients) (Marlatt & Witkiewitz, 2005)) and quitting smokers (40% of smokers who successfully abstained for one year and 90-97% of smokers who quit alone, (Shiffman, Kassel, Gwaltney, & McChargue, 2005)).

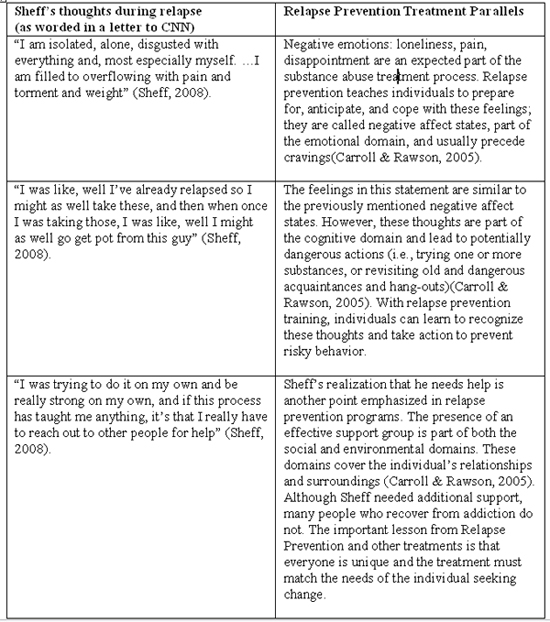

Illustrating people’s propensity for relapse, Nic Sheff, author of the addiction and recovery memoir, Tweak, (Addiction & the Humanities Vol. 4 (9) – Addiction is more than just science) suffered two relapses during May and October of 2008; these relapses were 3 and 8 months, respectively, after the publication of Tweak. Sheff explained that his relapse episodes were the result of a difficult personal situation and his attempt to deal with this situation alone. The specific difficulties of relapse that Sheff describes (see Table 1) are similar to those often reported for other addictive behavior: common characteristics of relapse include, negative automatic thoughts, mild depressive thoughts, negative emotions, cravings, and dangerous behavior (Marlatt & Witkiewitz, 2005; McKay, Rutherford, Alterman, Cacciola, & Kaplan, 1995).

Relapse prevention programs, self-management programs intended to facilitate maintained recovery ("Preface," 2005), attempt to account for many of the common difficulties associated with relapse. The foundation of relapse prevention is to encourage and assist treatment seekers as they work towards harm reduction, abstinence and moderation ("Preface," 2005) by focusing on the behaviors and environmental factors that make up each individual’s situation. Relapse prevention falls under the Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT) umbrella; its focus on individual factors means that each person’s treatment program should adapt to their learning and progress. Research suggests that relapse prevention is often effective for the treatment of addictive behaviors, including stimulant use disorders (e.g., Sheff’s methamphetamine addiction) (Carroll & Rawson, 2005). Table 1 presents some of the parallels in Sheff’s thoughts and behavior regarding his relapse (Bonifield, 2008; Sheff, 2008), and typical relapse prevention treatment efforts.

Table 1: Parallels between Sheff’s relapse and Relapse Prevention Treatment.

Conclusion

Recovery from substance use disorders is difficult because of the prevalence of relapse and the associated problems that accompany relapse episodes. In our last post about Nic Sheff, we interviewed a high school teacher who stated that reading about Sheff’s more difficult experiences (e.g., detox, AA and NA use, near deaths) was beneficial and made the dangers of drug use more evident to her students. Sheff’s public admission to relapsing twice shows readers that, even with successful periods of abstinence, recovering from substance use and remaining drug-free is a difficult struggle that can take many years to resolve.

– Ingrid Maurice

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

References

Bonifield, J. (2008). Relapse a constant threat, 'Tweak' author says, CNNhealth.com: CNN.com.

Carroll, K. M., & Rawson, R. A. (2005). Relapse Prevention for Stimulant Dependence. In G. A. Marlatt & D. M. Donovan (Eds.), Relapse Prevention: Maintenance Strategies in the Treatment of Addictive Behaviors, Second Edition (2 ed., pp. 416). New York: The Guilford Press.

Marlatt, G. A., & Witkiewitz, K. (2005). Relapse Prevention for Alcohol and Drug Problems. In G. A. Marlatt & D. M. Donovan (Eds.), Relapse Prevention: Maintenance Strategies in the Treatment of Addictive Behaviors, Second Edition (2 ed., pp. 416). New York: The Guilford Press.

McKay, J. R., Rutherford, M. J., Alterman, A. I., Cacciola, J. S., & Kaplan, M. R. (1995). An examination of the cocaine relapse process. Drug Alcohol Depend, 38(1), 35-43.

Moore, B. A., & Budney, A. J. (2003). Relapse in outpatient treatment for marijuana dependence. J Subst Abuse Treat, 25(2), 85-89.

Preface. (2005). (2005). In G. A. Marlatt & D. M. Donovan (Eds.), Relapse Prevention: Maintenance Strategies in the Treatment of Addictive Behaviors, Second Edition (pp. 416). New York: The Guilford Press.

Sheff, N. (2008). After relapse come terror, hope, CNNhealth.com: CNN.com.

Shiffman, S., Kassel, J., Gwaltney, C., & McChargue, D. (2005). Relapse Prevention for Smoking. In G. A. Marlatt & D. M. Donovan (Eds.), Relapse Prevention: Maintenance Strategies in the Treatment of Addictive Behaviors, Second Edition (2 ed., pp. 416). New York: The Guilford Press.

Anne M. Fletcher, MS, RD August 28, 2009

I would like to comment on the relapse article and also to solicit feedback. It’s my understanding that Sheff went to numerous 12-step treatment facilities, where it is not uncommon to be told that any use of any substance whatsoever is a relapse. Therefore, with his first “slip” (as I recall it began with taking some pills from his mother’s medicine cabinet), the abstinence violation effect went into full effect and he figured he had already blown it and may as well go “all the way.”So part of the problem is addressing what clients are taught in the first place about the concept of a lapse versus a relapse.

Clients are also commonly taught that, even if they never had any problem with a particular substance (e.g., alcohol, in the case of a pot-dependent person), use of the nonproblematic substance is still considered a relapse because it will increase the odds of a full-fledged relapse. I am seeking research supporting this notion.

Anne M. Fletcher

Author, Sober for Good

Richard Lee August 28, 2009

As a former worker in the UK alcohol treatment field, my view is that relapse prevention is the core business of any service for drinkers.

I do however feel sympathy for the predicament of ex-drinkers (& users) who, while working hard to completely reorientate their lives are condemned to chronic, respectable sobriety. Not only do the rest of us take for granted the pleasure – or release – of a temporary holiday from the mundane provided by alcohol, cannabis or whatever our drug of choice may be, it has been argued (by Andrew Weil & many subsequent authors) that is a basic human appetite – but one that those “in recovery” are forbidden to satisfy.

Should relapse prevention therefore include instruction self-induced euphoria? After all, aren’t most of the benefits we attribute to psychotropic drugs placebo effects anyway?