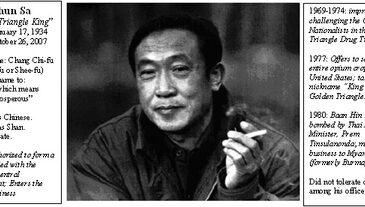

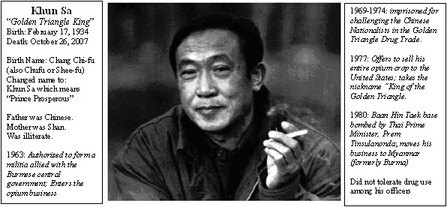

The guiding principle of supply and demand plays a key role in the indirect exchange between drug suppliers and drug users. In addition to local drug traffickers, there are also international drug rings whose successful operations make them essential collaborators in the drug business. One leader of such a drug ring was Khun Sa, whose life and death highlights differences in international government practices related to drug control. In this issue of Addiction and the Humanities, we use Khun Sa as a lens to examine the role of drug trafficking in the supply and demand that feeds drug addiction.

From 1974 to 1994, Khun Sa had unrivalled success and control over the growth and transport of opium, and its derivative, heroin, in the Shan State of Myanmar (formerly Burma) (AlJazeera.net, October 30, 2007; Economist, November 8, 2007). His rise to control came from a combination of confused reasoning and a government whose wish for economic and military aid clouded its judgment on how to deal with drug trafficking. Although never formally educated, Khun Sa received military training from the Chinese Nationalist forces. This experience no doubt proved valuable in commanding a local militia, and running his part of the already present opium business.

After moving his life and business to Myanmar (formerly Burma) (Fuller, November 5, 2007), Khun Sa maintained a love-hate relationship with both the Shan people and the Burmese Government; he argued that providing economic stability for the Shan people motivated him to engage in drug trafficking. In addition, although it publicly condemned him, the Burmese Government tolerated his control of Myanmar’s most economically rewarding export, and his arrangements with local police, soldiers, and generals. In 1996, the government reached a tacit agreement with Khun Sa ensuring that he would avoid extradition, receive government protection, and could retire comfortably; in return he had to surrender his home, weapons, ammunition, soldiers, refineries, and crops to the Burmese Government.

In 1977, Khun Sa offered to sell his entire opium crop to the United States (Johnson, March 1, 1982); this proposal suggested that buying his opium crop was the only way for the US to take it off the market and minimize the amount of opium traveling from Asia to the US. Khun Sa knew that his products, business, and influence stretched internationally, and with the Burmese Government’s help, he was able to avoid the consequences (e.g., indictment, extradition, trials) of international illegal activity. With the majority of demand for illegal drugs originating in the West, more specifically in the United States, foreign government cooperation with drug traffickers poses a threat to international attempts to put a stop to drug business’s power. In Khun Sa’s case, the Burmese Government enabled him in multiple ways. While Khun Sa controlled a personal army, the government accepted the idea of opium as a profitable crop and chose to ignore the evident negative effects on international relations. In fact, Khun Sa’s January 7, 1996 surrender to the Burmese Government placed a significant amount of weaponry and property in their hands.

Myanmar’s exit from the opium (heroin) business (Liu, November 6, 2007) made room for other Eastern countries’ re-entry. Afghanistan, for example, has regained its position as the number one producer of heroin in the East; 92% of the world’s heroin is now produced in Afghanistan (Liu, November 6, 2007). The situation in Afghanistan is similar to that in Myanmar: without sufficient government regulations, drug traffickers can impose their power and deceive nations into thinking that their drug transactions function like all other import/export businesses. The difference in philosophy between Eastern and Western government ideas explains why Khun Sa’s proposal to the United States was met with an indictment. In the US, illegal drug activity is punished on both ends of the supply and demand scale; however, similar to the Shan state, currently some Eastern nations have less demand and can focus on their role as suppliers to bring them financial stability.

What do you think? Comments can be addressed to Ingrid R. Maurice.

References

AlJazeera.net. (October 30, 2007). Golden Triangle drugs kingpin dies. Retrieved November 26, 2007, from http://english.aljazeera.net/NR/exeres/FA91ECD1-59CA-4963-83EE-34DCB6557F71.htm

Economist, T. (November 8, 2007). Obituaries: Khun Sa (Chang Chi-fu), master of the heroin trade, died on October 26th, aged 73. Retrieved November 19, 2007, from http://www.economist.com/obituary/displaystory.cfm?story_id=10097596

Fuller, T. (November 5, 2007). Khun Sa, Golden Triangle Drug King, Dies at 73. New York Times, Asia Pacific Section Retrieved November 19, 2007, from http://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/05/world/asia/05khunsa.html

Johnson, M. (March 1, 1982). The Great Opium War. Time Magazine Retrieved November 26, 2007, from http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,922799,00.html

Liu, M. (November 6, 2007). Death of the Golden Triangle’s most powerful druglord. Newsweek Retrieved November 19, 2007, from http://www.blog.newsweek.com/blogs/ov/trackback.aspx?PostID=65236

timada42 April 28, 2016

As far as I know Khun Sa maintained for years that he was a freedom fighter for the Shan, one of many ethnic minorities who for decades have battled the central government of Myanmar. I don’t know if it’s true, but knowing that the US government offered once a $2-million reward for his arrest proves he had a lot of power over the drug dealing.