At one point during their January 21st NFL playoff game against the Colts, the Patriots were winning by a score of 21 to 6. The Colts won the game by four points. How could the score change so drastically? What happened? If you were a Patriots fan watching the team while they were winning, and you suddenly had the thought, “There’s no way they could lose now,” did you inadvertently contribute to the game’s unexpected outcome? In their angst, many New England football fans might have wondered if their actions or thoughts during the game somehow influenced the sad and abrupt ending to the Patriots’ season.

Clinicians use the phrase magical thinking when referring to the belief that thoughts can influence outcomes. This belief is common in patients experiencing psychotic states. However, in small amounts, magical thinking can occur in just about anyone. Magical thinking often involves the illusion of control: a belief in our ability to influence events over which we have no control, no matter how irrational we know we are being by holding such a belief. It is magical thinking that explains our feeling of responsibility for our favored sports team winning or losing.

Pronin, Wegner, and McCarthy (2006) examined magical thinking within the context of the 39th Super Bowl, when the Philadelphia Eagles narrowly lost to the New England Patriots. The researchers surveyed 58 football fans: 16 Patriot fans and 39 Eagles fans. The fans had just finished watching the game on a big screen TV in their student center. The researchers asked them how much time they spent focusing on the game while watching and for which team they rooted. They also asked participants to rate their perceived feelings of control – how responsible they felt for the outcome of the game and whether they tried to influence the outcome of the game. Researchers combined these two variables into a single variable, “perceived control.” The researchers hypothesized that the amount of time spent focusing on the game would positively correlate with the degree of perceived control.

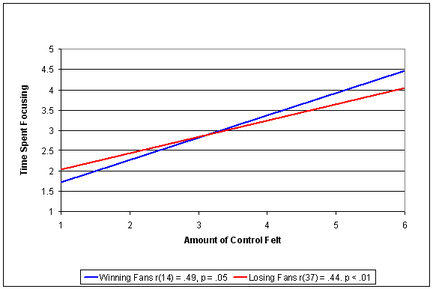

As shown in Figure 1, the more time fans reported focusing on the game, the more control they felt over its outcome, r(56) = .40, p < .01. The regression lines plotted in Figure 1 illustrate that the relationship was similar for both the fans whose team won (r = .49) and the fans whose team lost (r = .44). Though time focusing correlated significantly with control felt, the overall amount of control fans felt for the outcome was not particularly high; even those fans in the top 25% of time spent focusing on the game perceived themselves as having controlled the outcome only “very slightly” or “a little bit” (M = 2.48; 2 = very slightly and 3 = a little bit for the responsible and influence questions that comprise “perceived control”).

Fig. 1 Perceived Control Over Outcome in Winning and Losing Fans

There are a few limitations to this study. The survey is retrospective, meaning the participants had to remember how much they thought about the game, instead of rating their attention in real time, which could have led to recall bias. Furthermore, the study is correlational, which creates the possibility that those who happened to feel more control for the outcome might have perceived themselves as having focused more on the game.

This study demonstrates a possible link between people’s investment in an outcome (e.g., focusing on the game) and the control they feel over that outcome. The fans in the study were watching the game on television, fifty miles from the location of the game, yet still felt some control. Perhaps fans at the game focus on it more and feel even more control over the outcome. Casino gamblers physically interact with their games of chance – comparable to being on the stadium field. This context lends itself to a high amount of focus, and because, according to this study, focus on the game relates to feeling of control for both positive and negative outcomes, casino gamblers might be vulnerable to feelings of control over wining and losing money during the course of the game. This illusion of control over a gambling outcome might lead gamblers to believe that they can change losses into wins or perpetuate a winning streak by behaving in a particular way (e.g., using a lucky charm, only playing certain machines, etc.) Future research is necessary to see whether Pronin et al.’s findings replicate within a gambling setting where money is at stake. By testing the level of focus on a game, researchers can monitor how that focus relates to resulting feelings of control and how both variables influence gaming decisions.

What do you think? Comments on this article can be addressed to Leslie Bosworth.

References

Pronin, E., Wegner, D., McCarthy, K., Rodriguez, S. (2006). Everyday Magical Powers: The Role of Apparent Mental Causation in the Overestimation of Personal Influence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, (91)2, 218-231.