One Sunday morning in 1804, the British poet Thomas de Quincey woke up with an excruciating headache. On his doctor’s advice, he bought a bottle of laudanum (i.e., opium mixed with alcohol), and ended up using opium regularly for twelve years. In Confessions of an English Opium Eater (1820), written in a style between poetry and prose, de Quincey tells his story of opium use and addiction. Confessions was ostensibly written to warn people about the horrors of opium addiction, but unfortunately, because of de Quincey’s notoriety as a writer, it stirred enthusiasm for opium among artistic circles. For today’s readers, however, de Quincey’s experience – as eloquently portrayed in Confessions and vividly reflected in his poetry – serves to remind us of certain features of addiction that standard conceptions of this condition often fail to emphasize. For example: (1) The immediate effects of objects of addiction vary widely across individuals in ways that reflect individual and contextual attributes; (2) The nature of these immediate effects can change drastically with prolonged use, even to the point of changing from euphoric to dysphoric; and (3) Many people who decide to overcome their addiction achieve full recovery, sometimes without the benefit of treatment. In this Addiction and the Humanities article, we examine the ways in which de Quincey’s work illustrates some of these common features of addiction.

Perhaps the feature of addiction de Quincey’s experience most strikingly portrays is that drug use effects are in fact dependent on the interaction between the substance or behavior and the individual. This is contrary to the conventional wisdom, which assumes that the immediate effects of an object of addiction are uniform among all users. For example, although the National Institute of Drug Addiction (NIDA) website describes opium’s effects as “euphoric” and promoting “a feeling of calm and well-being,” de Quincey’s Confessions and poetry reveal that his experience was quite different. As an artist, de Quincey experienced and described opium’s effects almost exclusively in terms of vivid imagery, both imagined and in dreams. Opium seemed to possess “a specific power…not merely for exalting the colors of dream scenery, but also for deepening its shadows….”. He also felt that, contrary to the often cited dulling of the senses produced by opiates, opium “introduce[d] amongst [the mental faculties] the most exquisite order, legislation, and harmony.” And, whereas opiates often cause drowsiness, the poet exalted opium’s tendency to “excite and stimulate the system.”

De Quincey’s experiences with opium also challenge standard conceptions of the rewarding nature of objects of addiction. It is well known that addiction of almost any kind ultimately is likely to result in negative consequences, including social, financial, and health problems. However, standard conceptions of addiction often assume that the immediate effects of the object of addiction remain pleasurable – even if one must increase the behavior over time to maintain the rewarding effects. On the other hand, after several years of opium use, de Quincey experienced a subjective shift whereby opium began to cause immediate terror and anguish that lasted for hours. “After some years new and monstrous phenomena began slowly to arise in the imagery of my dreams, which translated everything into their own language.” Interestingly, this later stage of his addiction, as reflected in his poetry, was characterized by certain recurrent themes. For example, many of his nightmarish visions featured persecution and guilt:

I was stared at, hooted at, grinned at

By monkeys, by parakeets, by cockatoos…

I ran into pagodas, and was fixed for centuries at the summit;

I fled from the wrath of Brahma;

Vishnu hated me;

Seeva lay in wait for me…

I had done a deed, they said, that the ibis and the crocodile trembled at (p. 123).

Why would de Quincey continue to use opium when, in his words, “it cannot be supposed that any man can be charmed by its terrors?” (p. 135). He explained in Confessions that the agony of reducing the dose beyond a certain point was even worse than the agony of maintaining it. However, he became increasingly weak, ill, and depressed, eventually realizing that he would die if he continued using opium. He “determined, therefore, if that should be required, to die in throwing off this accursed chain” and stop using opium.

Because specific treatment for addiction was not available at that time, it is difficult to imagine that someone in such a state could possibly recover. In fact, the conventional wisdom still perpetuates the belief that people with addiction rarely recover. However, after undergoing many months of feeling “agitated, writhing, throbbing, palpitating, shattered” (p. 137), de Quincey finally succeeded and lived the rest of his life as a relatively happy and healthy man.

We often hear about cases of addiction with tragic endings; indeed, addiction is a tragic problem that too often destroys lives. Nevertheless, sufferers have reason to hope, because, with increased awareness of addiction and other mental illness, improved treatments, and human beings’ natural will to survive, it is becoming more and more common for people with even the direst cases of addiction to overcome their illness and learn to live normal lives.

What do you think? Comments can be addressed to Cheryl Browne.

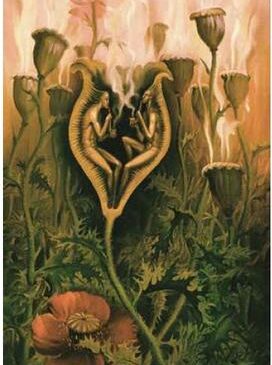

Image courtesy of Opioids: past, present, and future (www.opioids.com).

Notes

*In 18th and 19th Century England, the use of opiates, including morphine, heroin, and opium, was generally accepted by society. Originally used as analgesics for surgery, these pain relievers quickly became widely available to the public. As the “aspirin of its day,” people could purchase opium at any drug store or order these drugs through catalogues and have them delivered by mail. Manufacturers of products containing morphine or heroin touted them as therapeutic agents, their proposed uses including relief of all kinds of pain and calming of the nerves. Mothers were even encouraged to give syrups containing morphine to their fussy babies, particularly during teething.

References

de Quincey, T. (1928). Confessions of an English opium eater / The mail coach / Suspiria de profundis / Dream fugue. G. Saintsbury (Ed.). UK, Dial Press.