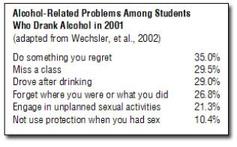

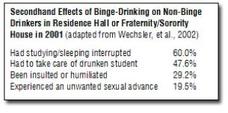

A recent study of college drinking behavior reveals that in 2001, 48.2% of students who consumed alcohol, drank to get drunk (Wechsler, et al., 2002). Alcohol, even in small servings, slows reflexes and impairs judgment; binge drinking* or drinking heavily can place people at greater risk for serious consequences, such as car crashes and date rape (NIAAA, 1995). Also disconcerting is a trend among female students: women are trying to drink as much alcohol, and as quickly, as their male counterparts. In April 2002, Time Magazine featured an article titled “Women On a Binge,” which discusses this phenomenon. The opening paragraph of the article quotes one senior woman at Syracuse University who describes two goals for her senior year: to learn how to drive a stick-shift and to “drink a guy under the table” (Morse et al., 2002). Women cannot metabolize alcohol as efficiently as men because they have lower levels of the enzymes that break down alcohol, and their bodies have a relatively higher fat to water ratio (NIAAA, 1999). Further, women are more likely to be victimized when intoxicated, and are more likely to experience long-term health consequences due to heavy drinking (NIAAA, 1999). When all these factors are considered, recent drinking trends among women and the potential consequences are reason for alarm.

These statistics might seem abstract to some; for those who might have difficulties imagining how they translate to real life, a new memoir by another 2002 Syracuse University graduate provides one possible narrative of the lifestyle suggested by the percentages above. In Smashed: Story of a Drunken Girlhood (2005), Koren Zailckas chronicles as much as she can remember of her relationship to alcohol: from her first drink at 14 and her first hangover a few months later, to getting her stomach pumped at 16, and then to her self-destructive binge-drinking and blackouts in college. Her drinking resulted in a sexual assault, caused her to vomit blood, and deleted from memory her late-night journey to an unfamiliar apartment in New York City. Though it is now obvious to the author that drinking resulted in very risky decisions and situations, the “beer goggles” she wore perpetually for a decade allowed her to ignore the risks and their roots.

These statistics might seem abstract to some; for those who might have difficulties imagining how they translate to real life, a new memoir by another 2002 Syracuse University graduate provides one possible narrative of the lifestyle suggested by the percentages above. In Smashed: Story of a Drunken Girlhood (2005), Koren Zailckas chronicles as much as she can remember of her relationship to alcohol: from her first drink at 14 and her first hangover a few months later, to getting her stomach pumped at 16, and then to her self-destructive binge-drinking and blackouts in college. Her drinking resulted in a sexual assault, caused her to vomit blood, and deleted from memory her late-night journey to an unfamiliar apartment in New York City. Though it is now obvious to the author that drinking resulted in very risky decisions and situations, the “beer goggles” she wore perpetually for a decade allowed her to ignore the risks and their roots.

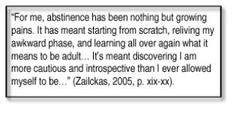

For Zailckas, alcohol served as an anesthetic to the awkwardness of adolescence and growing up: it allowed her to escape her feelings of shame and self-consciousness (Zailckas, 2005, p. xvi), while accentuating the more outgoing aspects of personality so well guarded when she was sober (Zailckas, 2005, p. 62). Drinking created a bizarre paradox: though Zailckas felt as though she had better control of the negative feelings she had about herself, in reality, these feeling emerged in more destructive ways when she was intoxicated. Alcohol is a mood magnifier. For example, instead of directly dealing with the feelings surrounding her sexual assault, Zailckas and a friend vandalized the fraternity house in which the man who assaulted her lived. Because she was less conscious of the impact of her experiences when drunk, she dealt with them in non-constructive ways. Using alcohol in this way is consistent with Khantzian’s self-medication theory (Khantzian, 1997), which suggests, in part, that individuals engage in behaviors, sometimes excessively and harmfully, to compensate for underlying problems and conflicts.

For Zailckas, alcohol served as an anesthetic to the awkwardness of adolescence and growing up: it allowed her to escape her feelings of shame and self-consciousness (Zailckas, 2005, p. xvi), while accentuating the more outgoing aspects of personality so well guarded when she was sober (Zailckas, 2005, p. 62). Drinking created a bizarre paradox: though Zailckas felt as though she had better control of the negative feelings she had about herself, in reality, these feeling emerged in more destructive ways when she was intoxicated. Alcohol is a mood magnifier. For example, instead of directly dealing with the feelings surrounding her sexual assault, Zailckas and a friend vandalized the fraternity house in which the man who assaulted her lived. Because she was less conscious of the impact of her experiences when drunk, she dealt with them in non-constructive ways. Using alcohol in this way is consistent with Khantzian’s self-medication theory (Khantzian, 1997), which suggests, in part, that individuals engage in behaviors, sometimes excessively and harmfully, to compensate for underlying problems and conflicts.

Zailckas employs poetic language to articulate an insightful analysis of her own behavior, most likely aided by the clarity of hindsight. Her memories and descriptions seem almost too good to be true, given the author’s state of intoxication during most of the experiences of which she writes. Nevertheless, Zailckas touches on issues to which women everywhere might be able to relate. She credits peer pressure, the drinking culture on college campuses and more generally, the advertising industry and their promotion of alcohol, as well as her desire to define, and be, ‘feminine,’ as factors contributing to her destructive drinking. Though the specific factors that influence drinking and the experiences that follow likely will be wholly unique for each individual, the influences and trends described in Smashed might be universal. In the introduction of her book Zailckas notes “Mine are ordinary experiences among girls and young women in both the United States and abroad, and I believe that very commonness makes them noteworthy” (Zailckas, 2005, p. xv). Whether or not every detail is accurate, this book creates a useful link between the statistics that describe drinking behaviors and the people behind those statistics.

Zailckas employs poetic language to articulate an insightful analysis of her own behavior, most likely aided by the clarity of hindsight. Her memories and descriptions seem almost too good to be true, given the author’s state of intoxication during most of the experiences of which she writes. Nevertheless, Zailckas touches on issues to which women everywhere might be able to relate. She credits peer pressure, the drinking culture on college campuses and more generally, the advertising industry and their promotion of alcohol, as well as her desire to define, and be, ‘feminine,’ as factors contributing to her destructive drinking. Though the specific factors that influence drinking and the experiences that follow likely will be wholly unique for each individual, the influences and trends described in Smashed might be universal. In the introduction of her book Zailckas notes “Mine are ordinary experiences among girls and young women in both the United States and abroad, and I believe that very commonness makes them noteworthy” (Zailckas, 2005, p. xv). Whether or not every detail is accurate, this book creates a useful link between the statistics that describe drinking behaviors and the people behind those statistics.

What do you think? Comments can be addressed to Siri Odegaard.

Notes

* Binge drinking is defined as drinking 5 or more drinks in a row for men, and 4 or more drinks in a row for women.

References

Khantzian, E. J., 1997: The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: A reconsideration and recent

applications. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 4: 231-244.

Morse, J., Bower, A., Healy, R., Barnes, S., Berestein, L., Locke, L. A., et al. (2002, April 1). Women On a Binge. Time Magazine, 159.

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (1995). Alcohol Alert No. 29. Retrieved April 17, 2005 from http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/aa29.htm.

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (1999). Alcohol Alert No. 46. Retrieved April 17, 2005 from http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/aa46.htm.

Wechsler, H., Lee, J. E., Kuo, M., Seibring, M., Nelson, T. F., & Lee, H. (2002). Trends in College Binge Drinking During a Period of Increased Prevention Efforts – Findings from 4 Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study Surveys: 1993-2001. Journal of American College Health, 50(5), 203-217.

Zailckas, K. (2005). Smashed: Story of a Drunken Girlhood. New York: Viking.