The Aviator (Logan, 2004), a new movie directed by Martin Scorsese about the life of Howard Hughes, opens with a shot of Hughes (Leonardo DiCaprio) as a boy being washed by his mother in a bath and warned about all of the disease and germs in the world. The movie emphasizes Hughes’ eccentric behaviors that were undiagnosed during his lifetime but later attributed to obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). Although the film’s attempt to draw a causal link between Hughes’ OCD and the interaction with his mother from the opening sequence is simplistic at best, The Aviator and its exploration of Hughes’ life provide an important perspective on individual expressions of mental illness. In this week’s review, we use DiCaprio’s and other portrayals of Howard Hughes to explore the classification of mental disorders in general, and the connections between OCD and impulse control problems, in particular.

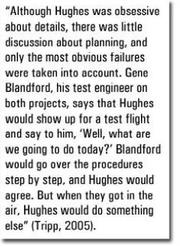

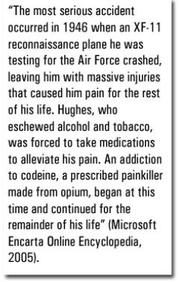

The Aviator paints a picture of Hughes as a paradox. On one hand, references to his OCD, a disorder characterized by harm avoidance, are laced throughout: Hughes struggled with symptoms of OCD from an early age, sorting his food into specific configurations before eating, suffering bouts of compulsive hand-washing, and repeating phrases over and over (e.g., “the way of the future”). The movie’s portrayal of Hughes is reinforced by other Hughes biographies (Bartlett & Steele, 2003; Channel Four Television Corporation, 2005; Greenstein, 1999; Tripp, 2005). Yet, scenes also show Hughes as a spontaneous lady’s man, a daring aviator, and an impulsive businessman. The movie and the sources mentioned above document impulsive and risky behavior such as making financial decisions on a whim and testing new airplanes without conducting pre-flight checklists or following flight plans once in flight. Accounts of Hughes’ publicly better known later life present a similar paradox. According to generally available sources (e.g., Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia, 2005), Hughes developed a serious drug dependence on the pain medications he received after suffering life-threatening injuries in a plane crash. Though Hughes avoided alcohol throughout his life and rarely gambled, this manifestation of drug dependence lasted the rest of his life. Hughes’ later life was most famously characterized by his OCD symptoms, reclusive behavior and paranoia, apparently fueled by an obsession with preventing exposure to germs; he was not typically characterized by his drug use.

Neither traditional classification schemes nor more contemporary continuous approaches can fully account for the pattern of symptoms we see Hughes exhibit in The Aviator. Traditional understanding of mental disorders in general, and substance use in particular, presents us with a conundrum. Using DSM-IV criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), Hughes could satisfy at least two different sets of diagnostic criteria by the end of his life: OCD, an anxiety disorder, and substance dependence, a disorder initially marked by impulse control problems. These disorders would be considered comorbid. A more continuous scheme, obsessive compulsive spectrum disorder theory (Hollander et al., 1996, see WAGER 9(47) for a description), would place these two disorders at opposite ends of the spectrum – one defined by avoidance behavior, the other by lack of inhibition. Neither of these approaches adequately account for the overlap between these apparently different disorders. DSM-IV addresses the problem of overlap by listing exclusion criteria for specific disorders (e.g., a diagnosis of pathological gambling cannot occur if mania is present), but cannot address overlap of disorders not specified within its exclusion criteria. Spectrum theories begin to account for how certain disorders might be related. However, these conceptualizations do not account for the expression of multiple disorders in one person.

Neither traditional classification schemes nor more contemporary continuous approaches can fully account for the pattern of symptoms we see Hughes exhibit in The Aviator. Traditional understanding of mental disorders in general, and substance use in particular, presents us with a conundrum. Using DSM-IV criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2000), Hughes could satisfy at least two different sets of diagnostic criteria by the end of his life: OCD, an anxiety disorder, and substance dependence, a disorder initially marked by impulse control problems. These disorders would be considered comorbid. A more continuous scheme, obsessive compulsive spectrum disorder theory (Hollander et al., 1996, see WAGER 9(47) for a description), would place these two disorders at opposite ends of the spectrum – one defined by avoidance behavior, the other by lack of inhibition. Neither of these approaches adequately account for the overlap between these apparently different disorders. DSM-IV addresses the problem of overlap by listing exclusion criteria for specific disorders (e.g., a diagnosis of pathological gambling cannot occur if mania is present), but cannot address overlap of disorders not specified within its exclusion criteria. Spectrum theories begin to account for how certain disorders might be related. However, these conceptualizations do not account for the expression of multiple disorders in one person.

The Aviator, in its attempt to explain Hughes’ behaviors, might be interpreted to suggest a third option: that his disorders were not comorbid, but rather expressions of the same underlying disorder. His substance dependence was a manifestation of his OCD and his generally impulsive behavior might have been exhibited in relation to his obsessions.* Hughes did not drink, though he was constantly in the presence of alcohol in Hollywood; he did not gamble, though he lived in Las Vegas for a good portion of his life (DeMatteo, 1999-2005). He did initiate his psychoactive drug use. Instead, pain medications were forced into his routine after his plane crash, and as such, potentially became a compulsion.** In The Aviator, both Hughes’ reckless use of his money and risky flying stunts are portrayed in the service of fulfilling an obsession – to make the best or biggest movie, plane, or airline and to become the fastest man on earth. Current diagnostic theories rarely account for context or different expressions of the same underlying mental problems. Though possibly understood by a clinician, diagnostic tools used in research likely would miss these connections.

The Aviator, in its attempt to explain Hughes’ behaviors, might be interpreted to suggest a third option: that his disorders were not comorbid, but rather expressions of the same underlying disorder. His substance dependence was a manifestation of his OCD and his generally impulsive behavior might have been exhibited in relation to his obsessions.* Hughes did not drink, though he was constantly in the presence of alcohol in Hollywood; he did not gamble, though he lived in Las Vegas for a good portion of his life (DeMatteo, 1999-2005). He did initiate his psychoactive drug use. Instead, pain medications were forced into his routine after his plane crash, and as such, potentially became a compulsion.** In The Aviator, both Hughes’ reckless use of his money and risky flying stunts are portrayed in the service of fulfilling an obsession – to make the best or biggest movie, plane, or airline and to become the fastest man on earth. Current diagnostic theories rarely account for context or different expressions of the same underlying mental problems. Though possibly understood by a clinician, diagnostic tools used in research likely would miss these connections.

In the first issue of the Basis, we introduced a syndrome model of addiction (see Shaffer et al., 2004, reviewed in WAGER 10(1)). Inherent in that model is the idea that addiction manifests as the interaction of a person and an object, and that pathological gambling, alcoholism, or other substance abuse are different expressions of the same underlying problem. The case of Howard Hughes, when considered with the syndrome model in mind, encourages the expansion of this perspective to a consideration of mental illness in general. An underlying mental disorder has the capacity to express itself in multiple ways, as the syndrome model suggests. As a corollary, a single behavior can be the expression of any number of different mental illnesses. Thus, Hughes’ OCD was expressed in a clear cut way as extreme germ phobia and repetitive cleansing, but also in less clear cut ways – perhaps as drug dependence or seemingly impulsive behaviors that served his obsessions.

In the first issue of the Basis, we introduced a syndrome model of addiction (see Shaffer et al., 2004, reviewed in WAGER 10(1)). Inherent in that model is the idea that addiction manifests as the interaction of a person and an object, and that pathological gambling, alcoholism, or other substance abuse are different expressions of the same underlying problem. The case of Howard Hughes, when considered with the syndrome model in mind, encourages the expansion of this perspective to a consideration of mental illness in general. An underlying mental disorder has the capacity to express itself in multiple ways, as the syndrome model suggests. As a corollary, a single behavior can be the expression of any number of different mental illnesses. Thus, Hughes’ OCD was expressed in a clear cut way as extreme germ phobia and repetitive cleansing, but also in less clear cut ways – perhaps as drug dependence or seemingly impulsive behaviors that served his obsessions.

But where does this movie leave us? Certainly not with a definitive understanding of Howard Hughes and his psychological composition. Not with a clear theory of the relation between impulse disorders and obsessive compulsive disorders. Perhaps The Aviator provides a perspective on mental illness that is not linked to our current diagnostic schema or tools that derive from that scheme. To move beyond movie seat psychiatric analysis, we need to translate that perspective into research unconstrained by categories and cut points that have not been empirically derived.

What do you think? Comments can be addressed to Sarah Nelson.

Notes

* Some biographies and theories hold that all of Hughes’ symptoms and behaviors were expressions of late stage neurosyphilis (e.g., Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia, 2005). If true, this supports the importance of considering more than overt behavior and symptoms in understanding mental disorder. In this case, the same behaviors and symptoms that define obsessive compulsive disorder would be manifestations of a completely different neurological disease.

** Thinking about the syndrome model presented in WAGER 10(1), one could argue that Hughes became dependent, but not addicted.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Bartlett, D. L., & Steele, J. L. (2003). Howard Hughes: His life and madness. London: Carlton Books.

Booth, W. (2004, December 19th). Leo and Howard. Washington Post, p. N01.

Channel Four Television Corporation. (2005). Howard Hughes: A chronology. Retrieved January 22nd, 2005, from http://www.channel4.com/history/microsites/H/history/e-h/hughes.html

DeMatteo, D. (1999-2005). Las Vegas Strip historical site. Retrieved January 22nd, 2005, from http://lvstriphistory.com/ie/hughes.htm

Greenstein, A. (1999). Howard Hughes. Retrieved January 22nd, 2005, from http://www.socalhistory.org/Biographies/h_hughes.htm

Hollander, E., Kwon, J. H., Stein, D. J., Broatch, J., Rowland, C. T., & Himelein, C. A. (1996). Obsessive compulsive spectrum disorders: Overview and quality of life issues. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 57, 3-6.

Logan, J. (Writer), & M. Scorsese (Director) (2004). The Aviator.

Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia. (2005). Hughes, Howard Robard. Retrieved January 22nd, 2005, from http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761553204/Howard_Hughes.html

Shaffer, H. J., LaPlante, D. A., LaBrie, R. A., Kidman, R. C., Donato, A., & Stanton, M. V. (2004). Toward a syndrome model of addiction: Multiple manifestations, common etiology. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 12(6), 367-374.

Tripp, R. S. (2005). Howard Hughes. Plane and Pilot Magazine, January.