Many Americans socialized during the Depression were unwilling to engage in gambling since they lacked the monetary means and feared the negative stigma once culturally associated with all forms of betting. Times have changed, however, as the youth of yesteryear’s Depression have become the seniors of today’s economic boom. Indeed, many seniors (i.e., aged sixty-five and older) have embraced gambling as a form of entertainment. These seniors use both disposable income and retirement time to gamble. However, some seniors have not fully embraced gambling. Research conducted by McNeilly and Burke (2000) shows the dissimilar profiles of these two groups.

McNeilly and Burke (2000) divided senior research respondents (n=315) into two groups: the first consisted of community-dwelling seniors with active participation in bingo parlors and day bus trips to casinos (n=91); the second consisted of community-dwelling seniors not actively involved in gambling at the time they agreed to participate in the research (n=224). Characteristics of the two groups were shown to be quite different: the active gamblers (i.e., those with active participation in bingo parlors and casino bus trips) were more likely than their non-active counterparts to currently smoke (14.8% vs. 3.8%), drive a car (88.9% vs. 57.8%), eat fewer than two meals a day (15.6% vs. 3.4%) and do volunteer work on an occasional basis (40% vs. 20%). In contrast, the group of non-active gamblers were more likely to spend time reading books several times per week when compared with the active gamblers sampled (57.1% vs. 42.2%) (McNeilly & Burke, 2000).

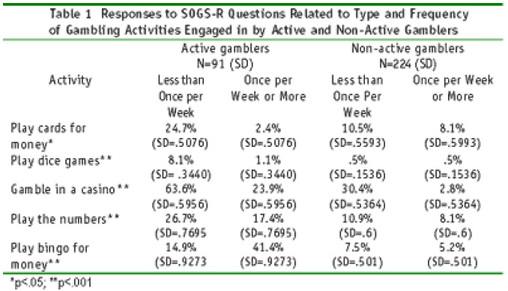

McNeilly and Burke (2000) conducted additional comparisons using the South Oaks Gambling Screen-Revised (SOGS-R). The researchers discovered that active senior gamblers participate with greater frequency in other gambling activities than currently non-gambling seniors. For instance, on a “less than once per week” basis, the active senior gamblers gambled in casinos (63.6%), on card playing (24.7%), on dice games (8.1%), on bingo (14.9%) and on the lottery (26.7%) more frequently than the non-active senior gamblers. Moreover, active senior gamblers were found more likely than their counterparts to gamble on a “once a week or more basis” in casinos (23.9%), playing bingo (41.4%), and playing the lottery (17.4%) (McNeilly & Burke, 2000). Interestingly, McNeilly and Burke (2000) also discovered that the non-active gambling group of seniors reported gambling on card playing with greater frequency on a “once a week or more” basis than the active senior gambling group. Table 1 presents the differing responses to SOGS-R questions related to type and frequency of gambling activities between active and non-active senior gamblers in some, but not all, of the gambling activities examined by McNeilly and Burke (2000).

While the research conducted by McNeilly and Burke (2000) contributes to an otherwise limited body of knowledge about senior gamblers and their gambling, this work is problematic. For instance, the sample group of active senior gamblers consists of those who currently are involved in bingo parlor and casino day trip activities. As such, and as Table 1 so reveals, it seems obvious that this group would play bingo for money and gamble at a casino more than the non-active gambling group on both a “less than once a week” and “once per week or more” basis. More importantly, however, what still remains undetermined is whether active and continued engagement in bingo and casino gambling activities of the active senior gambling group is out of interest alone, or the problematic need to participate in gambling activities caused by active and continued participation in the bingo and casino gambling activities. Additionally, despite the fact that the non-active gambling group at the time of the study was not currently engaged in gambling activities, it remains unclear whether and to what extent this group’s past gambling experience has effected their current SOGS-R response scores.

Indeed, if a participant in the non-active gambling group was not currently gambling at the time of the study but did actively gamble beforehand, are the differences in gambling frequency per gambling activity between active and non-active gambling seniors shown in Table 1 reflecting the participants surveyed or the current status of the participants’ gambling behavior at the time of the study? This discrepancy is not clearly addressed in the research. Despite these limitations, the work of McNeilly and Burke (2000) remains a significant contribution to the study of elderly gambling.

Their profile of both active and non-active senior gamblers might be the first step in identifying problem and pathological gambling among elderly populations. Moreover, their data inspire topics for future research, including the reasons why non-active gambling seniors gamble on card playing with greater frequency on a “once a week or more” basis than the active senior gamblers. Globally, the research conducted by McNeilly and Burke (2000) indicates that the study of elderly gambling requires more attention in order to address not only the potential harms gambling can cause the elderly, but to evaluate effective means of treatment designed solely with elderly issues in mind in preparation for the array of gambling issues this population might one day present.

References

McNeilly, D. P., & Burke, W. J. (2000). Late life gambling: The attitudes and behaviors of older adults. Journal of Gambling Studies, 16(4), 393-415.