The next time you visit your favorite mall or shopping center, look out for that person who hands out brochures filled with seemingly useless information. Rather than half-heartedly accepting a handout and immediately discarding it into the first available receptacle, you might want to examine the brochure. It could be more educational than you think.

A recent brief report conducted by Ladouceur, Vezina, Jacques and Ferland (2000) evaluated whether a brochure on pathological gambling could provide information to the general population. These investigators randomly recruited research participants from a shopping mall and municipal park (n=115) and assigned them to either a control or experimental group. Members of the experimental group received a brochure with a cartoon illustration of a video poker machine eating a gambler. The cover inside included the following specific gambling information: 96% of the population already has gambled during their lifetime and some people have developed a gambling addiction (Ladouceur, Boudreault, Vitaro, & Jacques, 1999; Ladouceur, Jacques, Ferland, & Giroux, 1999). In addition, the ten DSM-IV criteria for pathological gambling were listed. Lastly, the brochure provided information regarding specialized help for pathological gambling. Those assigned to the control group were not exposed to a brochure.

Later, the investigators asked participants in both the experimental and control groups a series of questions about problem gambling, the numbers of people they believe might have this problem, risky behaviors associated with problem gambling, and whether specialized help for problem gambling exists.

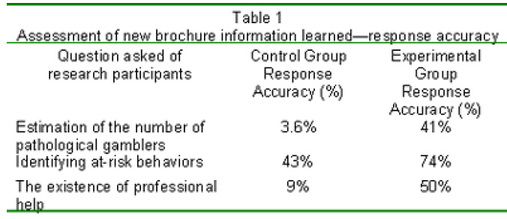

With regard to the first question, knowledge about problem gambling, 27% of the experimental group and 0% of the control group mentioned that 96% of the population has gambled. Moreover, 39% of the experimental group versus 13% of the control group reported that someone could indeed develop an addiction to gambling. Finally, 34% of the experimental group responded that gambling was a problem among youths while 12% reported that excessive gamblers always spend more money then they initially plan. The percentages of accurate responses among members of the control group to these same two questions were 11% and 4% respectively (Ladouceur et al., 2000). Table 1 summarizes the rate of accurate responses to the questions regarding the number of pathological gamblers, at-risk behaviors, and the existence of professional help.

Ladouceur et al. (2000) rightfully conclude that the brochure used in the study met with some success. The brochure presented new and arguably easily digestible information about problem gambling. Moreover, the brochure’s format and the quality of the information presented also received favorable comments from the experimental group[1] (Ladouceur et al., 2000). Consequently, we

can consider the brochure informative and useful.

However, additional attention must be given to the percentage of those within the experimental group that did not respond accurately. For instance, we might expect that more of those who saw the brochure would report that there is help available to treat problem gambling as opposed to those who did not see the brochure. However, 50% of experimental group respondents did not report any knowledge of the existence of specialized help, despite that fact that they were given a brochure with this specific information. Similar concerns exist regarding the experimental group’s relatively low rate of accurate responses regarding the estimation of the number of pathological gamblers and the identification of at-risk behaviors. Nevertheless, it is interesting to note that 43% of the control group could correctly identify risky behaviors associated with problem gambling.

It is difficult to precisely assess the impact of the informational brochures since the study did not indicate the time interval between the experimental group viewing the brochure and the researchers’ question session. Consequently, it is difficult to assess the total impact of the brochure. We cannot determine the duration of the brochure effect or whether people who read brochures talk with those who do not and extend the effect.

Despite these concerns, in this brief report, Ladouceur and his associates successfully demonstrate the importance of testing informational materials prior to public dissemination. They also reveal the need for more vigorous and enduring forms of public education about problem gambling.

[1] Such comments included, “it makes you think about the problem,” “it is well presented,” and “it must help people who have a problem” (Ladouceur et al., 2000).

References

Ladouceur, R., Vezina, L., Jacques, C., & Ferland, F. (2000). Does a brochure about pathological gambling provide new information? Journal of Gambling Studies, 16(1), 103-107.

Ladouceur, R., Boudreault, N., Vitaro, F., & Jacques, C. (1999). Pathological gambling and related problems among adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse, 8, 55-68.

Ladouceur, R., Jacques, C., Ferland, F., & Giroux, I. (1999). Prevalence of problem gambling: a replication study 7 years later. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 44, 802-804.