By definition, trends come and go. Arguably the same can be said for potentially addictive behavior patterns. In nineteenth century France, many free-spirits considered absinthe, a pale green liquor, as the key ingredient to what was then commonly known as l’heure verte, "the green cocktail hour." Consumed by nineteenth century notables Vincent van Gogh, Picasso, Oscar Wilde and the poets Charles Baudelaire, Paul Verlaine, and Arthur Rimbaud, absinthe touched and possibly damaged the lives of artists and commoners alike (Arnold, 1989; Strang et al., 1999). While its hallucinogenic properties attracted drinkers with the promise of new ideas, different experiences, and unique feelings, absinthe was eventually labeled a disease and banned in America and France in 1912 and 1915 respectively. This policy emerged as an increasing number of devotees were experiencing the drink’s often overlooked physically and psychologically debilitating properties (Arnold, 1989).

As a second era of absinthe use is just beginning to emerge with the availability of a less toxic form of the drink in Great Britain and a variety of absinthe-inspired paraphernalia on the internet, the United States is in the midst of its third era of widespread legalized gambling (Rose, 1986, 1995). Interestingly, however, unlike absinthe, with each passing era, gambling has become increasingly popular. This trend has been evident since it was first legalized in Nevada during 1931. The popularity of gambling advanced further when the first modern state lottery in New Hampshire was implemented during 1964. Its popularity continued to advance as Wall Street directed the contemporary diversification of Las Vegas. Indeed, other than the occasional scandals, gambling has never experienced the magnitude of decline in popularity and interest that absinthe did early in the twentieth century. This circumstance exists despite similar historical documentation of adverse consequences that accrued to persons considered addicted to gambling or absinthe. Turn of the century observers considered the behavior of people struggling with gambling addiction self-destructive and out of control (France, 1902, cited by Wildman, 1997, in Pathological Gambling, 1999). Even as early as 1866, Dostoyevsky’s The Gambler described the cognitive distortions, loss of control and self-esteem, and hopelessness that is today associated with clinical definitions of problem gambling (Pathological Gambling, 1999).

With clear documentation of gambling’s potential ills for some players, it remains unclear why or, more accurately, how gambling survived, adapted, and thrived while other potentially addictive behaviors, like absinthe consumption, had more difficulty reinventing themselves through the ages. Perhaps the innovation of the gaming industry itself is responsible for this resilience. For example, with the advent of new technology, hundreds of Internet gambling sites have emerged, and casinos have retooled and refurbished to appeal to the casual as well as the serious gambler.

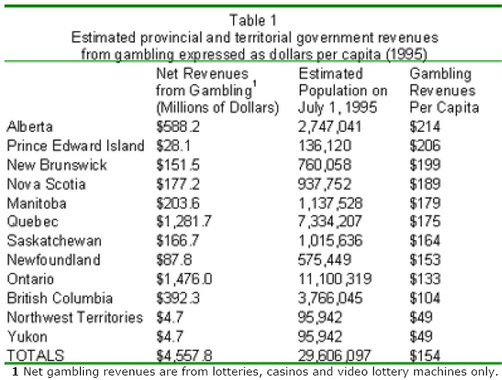

Perhaps another major reason why gambling has survived the challenges of time is because of government support. A study conducted by the National Council on Welfare (1996) on Canadian gambling argues that gaming revenues for governments are very attractive: as casino revenues have risen, so too has the government’s share of the profit. In 1995, the estimated net gambling revenues to the Canadian government from lotteries, casinos, and video lottery machines was $4.6 billion (Statistics Canada, in Gambling in Canada, 1996). As Table 1 illustrates, the government’s per capita share of casino revenue is striking considering that very little of this money is earmarked for specific government programs (National Council on Welfare, 1996).

Certainly not all governments receive the same level of revenue from gambling as does Canada. Moreover, there is variation between a government and its constituent agencies regarding the revenues received from gambling and the amount earmarked for government-sponsored programs and initiatives. More research is necessary to explore the details of this notion. However, we can speculate that one reason why some potentially addictive behaviors come and go while others come and adapt, is that some activities afford financial benefit to the government body that decides whether or not to sanction it 2. For instance, Table 1 shows that the tax burden in Alberta is $214 a person less than it might be because of gambling revenue. As a result, we can speculate that, in the absence of this revenue, Alberta’s government would have to raise taxes by $214 per person to maintain the programs and initiatives that would not otherwise be adequately funded (National Council on Welfare, 1996). State programs supported by lotteries provide similar examples of this new dependence upon gambling revenue within the United States.

There are likely many and varied reasons for the appeal of gambling over the ages. What factors do you think have sustained the popularity of gambling despite the host of potential problems that it can influence? How is gambling different from intoxicants? Who benefits and, perhaps more importantly, who is hurt by gambling? Submit an editorial or letter to the editor on this subject, or email the WAGER to voice your opinion.

Notes

It should be noted that government tax revenues from absinthe in the late nineteenth century made it hard for lawmakers to accept the dangers associated with the drink, as well as to legislate against its consumption (Arnold, 1989).

References

Arnold, W. M. (1989). Absinthe. Scientific American, 260(6), 112-117. National Council on Welfare. (1996). Gambling in Canada, from http://ccsa.ca./gambcont.htm.

National Research Council (1999). Pathological Gambling. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

Rose, I.N. (1986). Gambling and the Law (1st ed.). Hollywood, CA: Gambling Times.

Rose, I.N. (1995). Gambling and the law: Endless fields of dreams. Journal of Gambling Studies, 11, 15-33.

Strang, J., Arnold W. N., & Peters T. (1999). Absinthe: what’s your poison?: Though absinthe is intriguing, it is alcohol in general we should worry about. British Medical Journal, 319, 18-25.