Both the gaming industry and anti-gambling activists agree that underage gambling must be stopped. However, in spite of efforts by both sides and the government, underage gambling by minors continues to be a perennial problem. But how much of a problem?

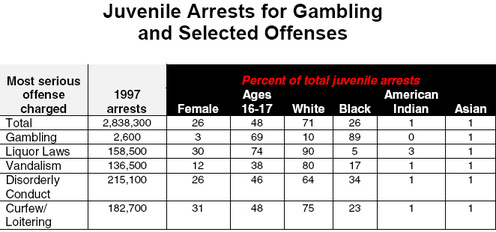

Obtaining estimates of juvenile involvement in gambling is a difficult task. Many offenses go undetected and minors may be understandably reluctant to self-report their illicit behavior to researchers. One source for estimating the magnitude of the problem is criminal justice data, available from the FBI and presented by the National Center for Juvenile Justice in their 1999 national report, which was prepared in cooperation with the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. The table below compares total 1997 gambling arrests with arrests for selected other crimes. The table also stratifies total arrests for a given crime by gender, age, and race/ethnicity.

The number of juvenile arrests for gambling pales in comparison to the numbers for selected other offenses. However, this discrepancy may be due to the "private" nature of gambling-related crimes. Liquor violations, vandalism, disorderly conduct, and loitering are often committed in public. The public nature of these crimes makes offenders easier to apprehend and arrest. That gambling is often a "behind-closed-doors" activity makes it a difficult offense to curb and prosecute. This public/private dichotomy may help explain the large differences in numbers of arrests.

It is interesting to note that although blacks constitute 26% of all juvenile arrestees, they represent 89% of all gambling-related arrestees. Similarly, whites make up 71% of total arrests, while they make up only 10% of gambling arrests. Why is this the case?

The higher arrest rate among blacks for gambling does not necessarily mean that blacks committed more gambling crimes. The number of arrests is not always proportional to the number of offenses committed. It is possible that blacks are more likely to be arrested for their gambling offenses than whites who commit the same crimes. It should similarly be remembered that the arrest data presented in the table represent the most serious offense charged. That is, a gambling-related charge of a juvenile who had concomitantly committed murder would not be recorded in the table.

One final observation: Sixty-nine percent of juvenile gambling offenses (and 74% of liquor law violations) are committed by adolescents between 16 and 17 years of age. Why this is so is a topic for a future WAGER. While arrest data can provide some insight into underage gambling, there are several limitations. Care should be taken when this data is used to gauge the prevalence of complex issues like underage gambling.

References

Snyder, H.N. & Sickmund, M. (1999). Juvenile offenders and victims: 1999 national report. Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.