It is difficult to remember our first exposure to surveys; they are truly ubiquitous. At some point in our schooling we may have been given the assignment of designing a survey: perhaps to determine how many children in the third grade watched a particular TV show, enjoyed celery, or had a red shirt. The task was simple then, and diligently we would canvass our classmates, asking them "if they had red shirts." To complete the assignment, we would then divide the number of positive responses by the total number of people surveyed. If only instrumentation were that simple.

Consider the possible criticisms that could be raised against our red shirt study. The wording of our question made it unclear whether we were interested in people who currently have red shirts, people who no longer own red shirts, or a combination of the two groups. Our definition of "red shirt" is equally ambiguous. How should people with burgundy or crimson shirts respond? If we were to repeat the survey later in the day when people were tired, might our findings differ? Since the question was asked in English, are our findings skewed by excluding the responses of visiting international students? Will third graders and fifth graders understand the question differently? Suddenly our simple assignment no longer seems simple.

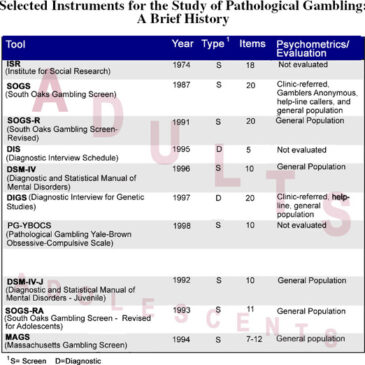

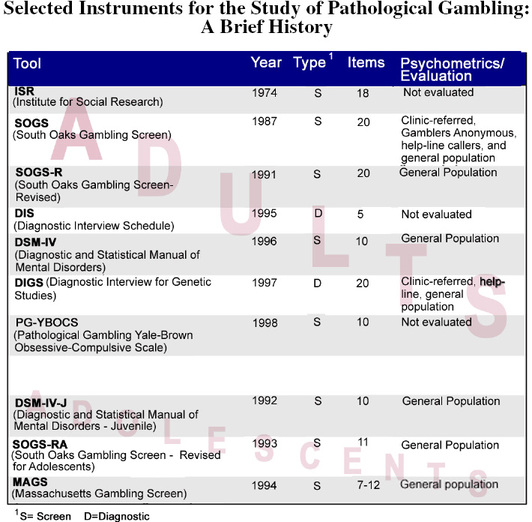

If the assignment of the red shirt survey presents difficulties, the task of creating an instrument with multiple items to identify pathological gamblers is daunting. And, indeed, the time between the creation of an instrument and its first administration may be several years. A brief, though hardly exhaustive, history of pathological gambling instruments is presented in the table below. Wherever possible, the table entries are linked to sites containing further information. Even after 25 years, controversies still exist about the best way to measure pathological gambling. Should the criteria be based on the dollar amount gambled? On the frequency of gambling? On the level of preoccupation with gambling? Even after these issues are tentatively settled by survey designers, many potential pitfalls remain: How should the questions be phrased? Does the order in which the items are presented matter? Are the instructions ambiguous or misleading? What ethical issues might the administration of this instrument raise?

The creation of valid and reliable instruments is a sizeable task for scientists, and several scholarly journals are devoted exclusively to the topic. When reading research on pathological gambling, it is critical to know what instrument was used to operationalize the phenomenon. Otherwise, we are likened to one asking about the temperature outside and not knowing whether the response was obtained from a precision laboratory thermometer, a digital sign outside of a bank, or from merely touching the glass of a kitchen window.

Table Source: National Research Council. (1999). Pathological gambling: A critical review. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

The WAGER is funded, in part, by the National Center for Responsible Gaming, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, the Andrews Foundation, the Addiction Technology Transfer Center of New England, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration Services, and the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment.