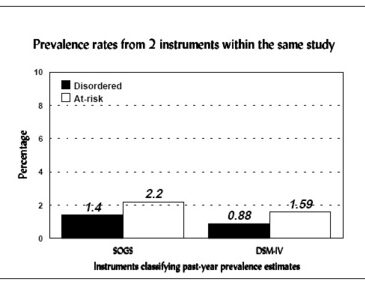

The previous WAGER examined some debatable issues associated with the denominator of pathological gambling prevalence estimates*. The numerator in pathological gambling prevalence estimates is no less complicated than the denominator. Although the numerator of a prevalence estimate portrays the number of individuals with disordered gambling over a specified period of time, reasonable people disagree about what exactly is disordered gambling. Pathological gambling does not (yet) have a marker that can identify an individual as a “case.” Thus, the parameters of given measurements determine this disorder. Common instruments used to identify “cases” of pathological gamblers include the SOGS, DIS, MAGS, and the DSM. Each instrument includes a series of questions about behaviors or thoughts that gambling may affect. Clinicians and researchers determine disordered gambling, whether called “pathological gambling,” “probable pathological gambling,” “problem gambling,” or other nomenclature, by setting a cut-off score above which the respondent can be considered a “case.” The specific cut-off score is discretionary, but usually informed by research findings and cultural values. In a clinical setting, whether a person meets the cut-off score isn’t typically considered as important as whether that person has a meaningful cluster of behaviors which has been influenced adversely by gambling activities. Cut-off scores enable researchers to determine the number of individuals with disordered gambling who make up the numerator of the prevalence estimate. The criteria for disordered gambling and the corresponding cut-off scores vary by instrument. Meeting 5 or more criteria out of 20 on the SOGS results in the same classification as meeting 5 or more criteria out of 10 on the DSM-IV. In a prevalence study of 1654 adults in New York**, researchers used two instruments to estimate disordered gambling. Although these estimates may look similar, the differences between the estimates may have important practical policy or clinical program consequences.

Sources:

*Prevalence, denominators, and determination of at-risk. (1997, June 17). The WAGER, 2(25), 1.

**Volberg, R.A. (1996). Gambling and problem gambling in New York: A 10-year replication suvey, 1986-1996 (Report to the New York Council on Problem Gambling). Roaring Spring, PA: Gemini Research.

This public education project is funded, in part, by The Andrews Foundation.