A television advertisement begins with a group of young men and women setting up a platform and chairs; onlookers stop and stare. The caption on the screen reads, “Outside a major tobacco company.” After the stage is assembled, a young woman steps up to the podium and states that tobacco companies have been targeting women for 70 years and suggesting that smoking could help women find their own voice. Then, an older woman steps up to the microphone and, using her electronic voice box, says “Is this the voice you expected me to find?” The commercial, one of many created by the Truth campaign, makes a dramatic and poignant statement about the tobacco industry. You may have heard or seen one of these Truth commercials on the radio, TV, the Internet or posted on billboards, as they are prevalent nationwide. They seem to be everywhere. With promotions for all kinds of products found in all facets of life, advertisements in general have become intertwined with society. Because successful ads continue to receive funding and unsuccessful ads are discontinued, popular ads could be seen as a reflection of culture. The Truth ads seem to be popular and notable; but, are these particular ads having any impact on young smokers?

At first glance it might seem like the Truth campaign ads would not appeal to most young people today for one plain and simple reason: young people do not like being told what to do, and the content of these announcements is clear – don’t smoke. In fact, if the target audience knew that parents and authority figures backed the anti-smoking campaign, they might resist the message and even start smoking just to challenge its supporters. I might have believed all this had I not witnessed the inner workings of the Truth promotion firsthand.

A recent personal experience with these commercials in Cambridge, MA, has influenced my opinions about the Truth campaign. Just a few months ago, while walking through Harvard Square, a person working for the Truth campaign stopped me and asked me to state my opinion about the tobacco industry for a possible inclusion in one of their commercials. I stared into the camera, as people do in many of these TV ads, and stated my self-admittedly canned response about the tobacco industry’s disgraceful advertisement campaign aimed at children (e.g., Joe Camel). When I finished my rant, I recognized that, although I had half-heartedly agreed to the promotion, I DID feel angrier at the tobacco lobby after voicing my opinion. And the students who had egged me on during my speech only fomented my fury. I was beginning to see how the Truth campaign worked its magic.

But my anecdotal experience does not provide sufficient evidence for the efficacy of the campaign. For that, empirical research is necessary. Studies have shown that the Truth campaign is successful in encouraging anti-tobacco attitudes and beliefs among 12-17 year olds (Farrelly et al., 2002). In addition to creating negative attitudes and beliefs, the Truth campaign is associated with “lower receptivity to pro-tobacco advertising and less progression along a continuum of smoking intentions and behavior” (Hershey et al., 2005, p. 22). This means that those who watched the Truth ads were less likely to start smoking or increase their smoking habits. In fact, these ad campaigns have been quite successful, even compared to anti-smoking campaigns in the classroom. Meta-analytic research shows very little long-term benefit to many school-based programs (Wiehe, Garrison, Christakis, Ebel, & Rivara, 2005); large-scale survey research, on the other hand, shows that the Truth campaign has a significant desired long-term effect on adolescent smoking attitudes and behaviors (e.g., increase negative attitudes toward smoking and decrease smoking behaviors) (Farrelly, Davis, Haviland, Messeri, & Healton, 2005; Farrelly et al., 2002).

Given the evidence, Truth ads do provide a meaningful way to increase anti-tobacco cognition and reduce the progression of smoking among a broad population of young people. One recent article suggests that the success of the campaign’s new ads is a result of targeting the insecurities of young people; their message is “You’re a tool if you get duped by [tobacco companies’] manipulative marketing techniques. Do you want to be a tool, kids?” (Stevenson, 2005). I suggest that the success of the Truth campaign comes from: (1) in its ability to draw the viewer in with catchy market ploys, (2) the constant presence of these ads on the TV, radio, and billboards, and finally (3) the ability of the campaign to identify with the young American consumer.

I also found myself persuaded by the advertisements in these three ways. I was drawn into participating in the ad because of its unique marketing strategy; I felt comfortable agreeing to join because I had recognized their slogans all over the media; finally, I found myself identifying with the young spokespeople and students who egged me on. These are personal explanations for why the campaign works, but future research will be necessary to identify the elements that contribute to the success of the anti-smoking Truth campaign.

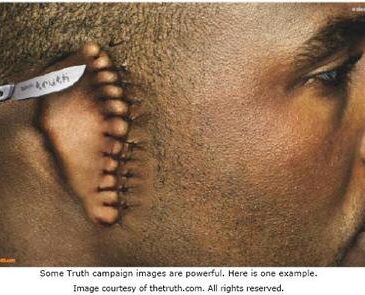

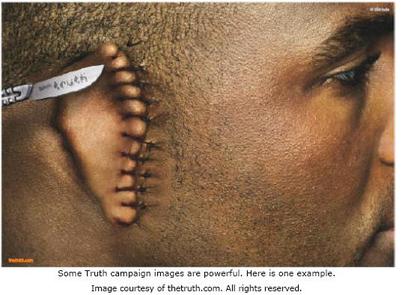

The success of the Truth campaign is a heralding call to public health advocates that mass media campaigns can have an impact on young people. Perhaps those interested in preventing the spread of HIV, Hepatitis, and similar public health crises can look to the Truth campaign model for pointers. Unfortunately, the future of the Truth campaign remains uncertain. As of March 2003, tobacco companies are no longer obligated to contribute to the center that funds these ads. This could signal an end to the successful Truth media campaign. Ads are expensive; without sufficient funding, this campaign cannot continue (Krisberg, 2004). If, as stated in the introduction, advertisements have almost become a reflection of our culture, this could suggest that funding for anti-tobacco propaganda is losing public support. Fortunately, a new series of ads on the Truth campaign’s website seems to suggest that the truth campaign is not licked yet.

What do you think? Comments can be addressed to Michael Stanton.

References

Farrelly, M. C., Davis, K. C., Haviland, M. L., Messeri, P., & Healton, C. G. (2005). Evidence of a dose-response relationship between "truth" antismoking ads and youth smoking prevalence. American Journal of Public Health, 95(3), 425-431.

Farrelly, M. C., Healton, C. G., Davis, K. C., Messeri, P., Hersey, J. C., & Haviland, M. L. (2002). Getting to the truth: evaluating national tobacco countermarketing campaigns. American Journal of Public Health, 92(6), 901-907.

Hershey, J. C., Niederdeppe, J., Evans, W. D., Nonnemaker, J., Blahut, S., Holden, D., et al. (2005). The theory of "truth": how counterindustry campaigns affect smoking behavior among teens. Health Psychology, 24(1), 22-31.

Krisberg, K. (2004). Successful ‘Truth’ Anti-Smoking Campaign in Funding Jeopardy: New Commission Works to Save Campaign. Nation’s Health, 34(4).

Stevenson, S. (2005, March 7). How to get teens not to smoke: Prey on their insecurities. Slate, http://slate.msn.com/id/2114440/.

Wiehe, S. E., Garrison, M. M., Christakis, D. A., Ebel, B. E., & Rivara, F. P. (2005). A systematic review of school-based smoking prevention trials with long-term follow-up. Journal of Adolescent Health, 36(3), 162-169.