The satire Thank You for Smoking raises several important questions about tobacco and film; it also provides an inside look at the incentives behind product placement in movies. The film, based on Christopher Buckley’s novel, stars Aaron Eckhart as Nick Naylor, a deft and persuasive lobbyist who represents the fictional research institute The Academy of Tobacco Studies, aptly nicknamed, Big Tobacco. The Academy of Tobacco Studies does its part to increase profits for the smoking industry by marketing studies that denounce the link between smoking and cancer based on experiments conducted by a dubious looking European scientist with questionable credentials releasing unknown fumes into a glass cage of rats.

In the movie, the leaders of The Academy of Tobacco Studies meet to discuss their major problem: declining smoking rates in the United States. Naylor’s boss vents, “We don’t sell Tic Tacs – we sell cigarettes. And they’re cool, available, and addictive. The job is almost done for us!” He explains that, in 1927, when moving pictures debuted, actors were portrayed smoking onscreen, which immediately launched the smoking boom. He laments that, in 1952, Reader’s Digest published concerns about tobacco’s harmful effects on one’s health, an event that helped shape today’s antismoking campaigns.

During the meeting, Naylor delivers a rousing speech about how the early 20th century movies “made smoking sexy” but now the only people smoking onscreen are either “psychopaths or Europeans.” He urges Big Tobacco to “put the sex back into cigarettes” by bribing Hollywood producers to have actors smoke onscreen. He claims, “The message Hollywood needs to send out is ‘Smoking Is Cool!’”

When this measure is enthusiastically approved, Naylor flies to Los Angeles to persuade a slick agent, Jeff Megall, to use tobacco product placement in his next big blockbuster, set in space. Megall agrees readily, as product placement will ensure substantial funding from The Academy of Tobacco Studies. This is one area where reality diverges from Hollywood – in actuality, cigarette producers that joined the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement with 46 states are prohibited from funding films for product placement (Szabo, 2005).

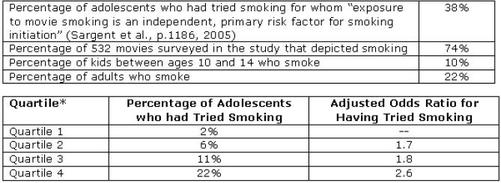

Naylor and Megall are confident that showing Brad Pitt and Catherine Zeta-Jones smoking onscreen in a romantic scene will revitalize smoking rates, especially if they launch a new cigarette by the same name as the movie, Sector Six, and at the same time as the film. A recent study (Sargent, Beach, Adachi-Mejia, Gibson, Titus-Ernstoff, Carusi, Swain, Heatherton, & Dalton, 2005) provides evidence suggesting that this practice might work. The study suggests that “exposure to movie smoking is the primary independent risk factor for smoking initiation in US adolescents” between ages 10 and 14 (Sargent et al., p.1183, 2005).

The researchers interviewed 6,522 randomly selected adolescents aged 10 to 14 years across the country. They estimated participants’ exposure to viewing smoking onscreen in 532 recent box-office hits (the top 100 US box-office hits per year from 1998 to 2002 and 32 movies that earned at least $15 million in gross US box-office revenues from January to April of 2003) and examined the influence of onscreen smoking on these adolescents. Researchers found that the adolescents who viewed the most tobacco use onscreen were more than 2 ½ times more likely to start smoking than the adolescents who viewed the least tobacco use onscreen (Sargent et al., 2005).

PREVALENCE OF SMOKING AMONG ADOLESCENTS, ADULTS, AND ACTORS IN FILMS (ADAPTED FROM SARGENT ET AL., 2005)

* “Quartile of movie smoking exposure was significantly associated with the prevalence of smoking initiation” (Sargent et al., p.1183, 2005).

Of course movies are not the only reason young people start using tobacco: children see smoking everywhere, including on commercials, in magazines, by musicians, on television, and by adults around them. The researchers found that other strong to moderately strong factors that influenced smoking initiation were age, peer smoking, sensation seeking, rebelliousness, school performance, and maternal responsiveness (Sargent et al., 2005). Because the researchers could not randomly assign the adolescents to different experimental conditions (e.g., greater or lesser exposure to smoking in film), their results cannot be assumed to be causal. However, when impressionable youngsters see their favorite actors lighting-up in movies, they might be more willing try smoking than those who do not see this kind of modeling. Furthermore, cigarettes often are used to start conversations in films (e.g., one character asking another for a light). This circumstance can give the impression that smoking eases socially awkward situations. Controversy over the role that onscreen smoking plays in smoking initiation among adolescents has led some antismoking groups to urge that all movies that depict smoking should be rated R and that parents should shield their children from watching movies portraying smoking. Likewise, Sargent et al. (2005) suggest that limiting the exposure of children to smoking in movies could have important public health effects.

The film Thank You for Smoking indeed raises interesting questions about the effect of portraying onscreen smoking on audiences’ likelihood to start smoking. Naylor and Megall are convinced that using product placement will jumpstart the smoking rate after audiences realize that smoking is “sexy” again. Sargent et al.’s study (2005) provides evidence suggesting that the characters’ assumption is correct. One wonders what effect Thank You for Smoking will have on audiences’ likelihood to start smoking, especially because not a single character lights-up during the movie.

What do you think? Comments can be addressed to Audrey Bree Tse.

References

Sacks, D. O. (Producer) & Reitman, J. (Director). (2006). Thank You for Smoking [Motion picture]. United States: Fox Searchlight Pictures.

Sargent, J. D., Beach, M. L., Adachi-Mejia, A. M., Gibson, J., Titus-Ernstoff, L., Carusi, C., Swain, S. D., Heatherton, T. F., & Dalton, M. A. (2005). Exposure to movie smoking: its relation to smoking initiation among US adolescents. Pediatrics, 116(5), 1183-1191.

Szabo, L. (2005, November 6). Movies inspire children to smoke. USA Today.