Parents and youth advocates have raised concerns about media messages that depict substance use targeted to children. Bolstering this concern, research has shown a causal relationship between tobacco campaigns targeted to youth (e.g., the cartoon character Joe Camel) and increased tobacco consumption among youth (Fischer, Schwartz, Richards, Goldstein, & Rojas, 1991; Pierce et al., 1991). Media influence on children also might be associated with movie industry campaigns. Although many children routinely watch G-rated animated films, few studies have investigated whether these films convey messages about substance use. This week, Addiction and Humanities reviews a study investigating the depiction of substance use in G-rated animated feature films (Thompson & Yokota, 2001).

Thompson and Yokota reviewed 86 G-rated animated feature films that met the following study inclusion criteria: first released in theaters, available on videocassette for sale or rental in the United States on or before October 2000, recorded in English, and at least 60 minutes in length. For each film, researchers recorded the year of film release in theaters, length of movie, the type of substance shown, the duration of substance use shown, whether the film showed a physical effect of the substance, and whether the film conveyed a health message. The authors used Spearman’s rank correlation to test their hypothesis that depiction of substance use in G-rated animated feature films

has increased over time with new film releases1.

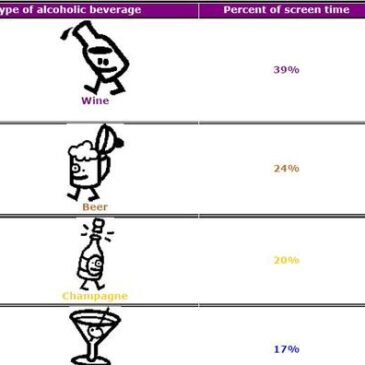

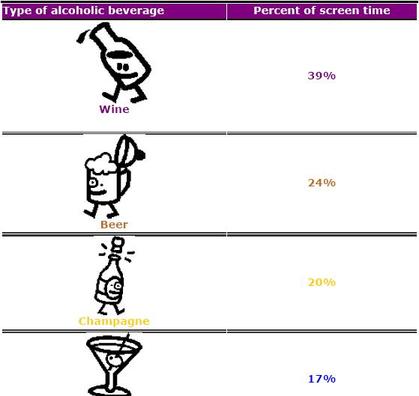

Thirty-eight films showed depictions of alcohol use lasting from two seconds to three minutes, with an average of 42 seconds of alcohol use. Table 1 shows the type and frequency of alcoholic beverages depicted in these films.

Table 1: Depiction of alcohol in sample of 38 G-rated animated films

Fifteen of these 38 films depicted the effect of drinking (e.g., staggering, hiccups or flushed face). None of the films contained a health message about the dangers of excessive alcohol use. The authors hypothesized that substance use in G-rated animated feature films has increased over time with new film releases. However, results show the trend has been away from depicting alcohol use in films (. = -0.22; p < .05). Results were similar when adjusting for length of films. No films showed depictions of illicit drug use; however, three films showed at least one character consuming a magical food, pill or potion that transfigured them (i.e., Alice in Wonderland, Snow White and We’re Back! A Dinosaur’s Story) and two films showed characters using a syringe to inject a substance into another character (i.e., The Secret of NIMH and Doug’s First Movie).

Since film illustrations of substance use are open to the authors’ interpretation, there are some limitations to the scientific rigor of analyses presented in the study. For example, the authors assumed that characters smoking pipes, including the caterpillar smoking a hookah in Alice in Wonderland, were smoking tobacco rather than smoking an illicit substance. Others viewing Alice in Wonderland might interpret the content of certain scenes in this film differently. For example, Grace Slick, singer in the rock band Jefferson Airplane, wrote the song White Rabbit about the hallucinatory effects of LSD depicted in Alice in Wonderland (Jefferson Airplane: The Band, 1998). In addition, the authors only recorded a depiction of substance use if the substance itself was in view. This interpretation might underestimate the representation of the substance use effects shown in the films. For example, the authors did not record the presence of the drunken character Uncle Waldo in The Aristocats as a depiction of alcohol use since the film never shows Uncle Waldo drinking or holding an alcoholic beverage. Because there are no universal standards for recording substance use in films, different interpretations might yield different findings.

According to results from this study, G-rated animated films frequently depict alcohol use without showing the long-term, potentially hazardous consequences. Statistical analyses show there has been some decrease in depiction of substance use in G-rated animated feature films over time. This study does not provide evidence about whether children’s viewing of these depictions of substance use has an effect on their substance using behavior. However, given the uncertainty of how children interpret the depiction of substance use in films, the American Academy of Pediatrics (1995) recommends that parents engage children in a discussion of film content to teach children the potential dangers associated with substance use.

What do you think? Comments can be addressed to Allyson Peller.

Notes

1. The authors also conducted regression analyses to test this hypothesis.

References

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Communications. (1995). Children, adolescents and television. Pediatrics, 96, 786-787.

Fischer, P. M., Schwartz, M. P., Richards, J. W., Jr., Goldstein, A. O., & Rojas, T. H. (1991). Brand logo recognition by children aged 3 to 6 years. Mickey Mouse and Old Joe the Camel. Journal of the American Medical Association, 266 (22), 3145-3148.

Jefferson Airplane: The Band. (1998). Retrieved June 7, 2006, from http://www.jeffersonairplane.com/grace.html

Pierce, J. P., Gilpin, E., Burns, D. M., Whalen, E., Rosbrook, B., Shopland, D., et al. (1991). Does tobacco advertising target young people to start smoking? Evidence from California. Journal of the American Medical Association, 266(22), 3154-3158.

Thompson, K. M., & Yokota, F. (2001). Depiction of alcohol, tobacco, and other substances in G-rated animated feature films. Pediatrics, 107(6), 1369-1374.