Historically, effective treatment for gambling disorders has been an elusive goal, considering that only a very small proportion of gamblers ever seek treatment (Cunningham, 2005). Brief treatment, which typically involves treatment of ten sessions or less, has been effective with alcohol related problems. Therefore, an adaptation of the brief treatment model might be equally effective for disordered gamblers unwilling to seek formal treatment. This week’s WAGER reviews a report by Hodgins, Currie, Currie, and Fick (2009) in their continuing research on brief treatment variations.

Methods

- Researchers used a randomized control study design and recruited 314 problem gamblers interested in reducing their gambling.

- At baseline, researchers gathered data about participants’ demographics, gambling history, use of public resources for gambling treatment, and gambling severity.

- Researchers assigned participants to one of four conditions:

- Brief Treatment (BT) participants received a self-help workbook after one half-hour telephone session of motivational interviewing (MI). The workbook provided self-assessments for gambling problems, practical recovery strategies, and information about local resources.

- In addition to the initial MI and workbook, Brief Booster Treatment (BBT) participants received six more brief telephone MIs at 2, 6, 10, 16, 24, and 36 weeks.

- Workbook Only Control (WOC) participants received the workbook without MI contact.

- Waiting List Control (WLC) participants waited six weeks before receiving the workbook, and had no MI contact.

- For all four conditions, researchers conducted follow-up assessments at 6, 12, 24, 36, and 52 weeks after initial contact. During these assessments, researchers collected measures of gambling prior to follow-up interviews.

Results

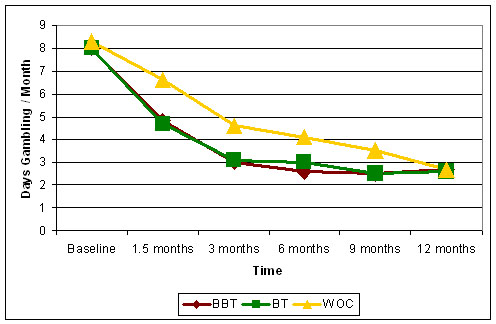

- After 6 weeks, BT and BBT participants reported significantly lower rates of gambling days per month than WOC and WLC participants. (M = 4.7, SD = 6.0; M = 4.8, SD = 5.9; M = 6.6, SD = 7.3; M = 5.7, SD = 6.4, respectively.)

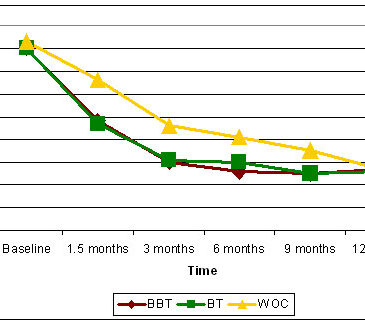

- As Figure 1 shows, participants across the BBT, BT, and WOC conditions reported significantly lower rates of gambling at all follow-up assessments

- At the 12-month follow-up, neither BT nor BBT gambling rates differed significantly from WOC. (BT vs. WOC, χ2(1, N = 249) = 3.0, p = ns; BBT vs. WOC, χ2(1, N = 249) = 2.1, p = ns).1

Figure 1 – Gambling Rates at Follow-Up Assessments (adapted from Hodgins et al, 2009).

- For ethical reasons, researchers could not retain participants on a waiting list for the duration of the study; therefore all participants received some form of treatment during the study year.

- Participants volunteered for the clinical trial, and were interested in reducing their gambling, so the results are not generalizable to all gamblers.

Discussion

Similar to Hodgins et al.’s original study (2001), the results of this experiment highlight the efficacy of brief treatments with or without motivational therapy. Though the follow-up findings from Hodgins original study found larger differences between MI and non-MI groups (Hodgins et al., 2004) than the current study, one consistent result across these three reports is a steady decline of problem gambling, without much distinction between the types of treatment. One possible explanation is that problem gamblers naturally regress from their addiction, regardless of treatment or treatment type. An important point to consider is that all participants in these studies received follow-up interviews to collect data; therefore, another possibility is that contact, whether motivational or not, was enough to affect gambling behavior.

A noticeable similarity between the three studies is the self-selected nature of the participants. Only gamblers who expressed interest to reduce or quit their problem behavior were recruited as participants. For future studies, the inclusion of moderator and mediator variables, such as participant expectations and readiness to change, would help clarify the mechanisms through which these interventions are effecting change.

-Aaron Lim

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

Footnote: Measures for WLC follow-ups after six weeks were not reported.

References

Cunningham, J.A. (2005) Little use of treatment among problem gamblers. Psychiatric Services, 56, 1024-1025.

Hodgins, D. C., Currie, S. R., & el-Guebaly, N. (2001). Motivational enhancement and self-help treatments for problem gambling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69(1), 50-57.

Hodgins, D. C., Currie, S. R., el-Guebaly, N., & Peden, N. (2004). Brief motivational treatment for problem gambling: A 24-month follow-up. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 18(3), 293-296.

Hodgins, D.C., Currie, S.R., Currie, G., & Fick, G.H. (2009). Randomized trial of motivational treatments for pathological gamblers: More is not necessarily better. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(5), 950-960.

Norman G. Hoffmann, Ph.D. July 21, 2010

Days of gambling may be an arbitrary metric (reliable, scientifically valid, and irrelevant to the real world – Kazdin, A. E. (2006). Arbitrary metrics: Implications for identifying evidence-based treatments. American Psychologist, 61(1), 42-79.). While days of use may be a good indication for level of problems, the amount lost, and other consequences of the gambling would seem to be required to provide context for days of use.

Charles Vorkoper July 22, 2010

Thanks for the study and presenting it. There are two comments:

1. Is there a plan for follow up with this client population? I was thinking at intervals of 6 months and a year. This gets at the question of change in a different way and is important when we are budgeting money for programs designed with deifferent treatment orientations.

2. The variables introduced by the persons who conduct the MI should be teased out in future studies. It would be very important to use staff that are recovering gamblers (or other addictions) and those who have no history of addiction.

3. The question about where stopping gambling leaves the client population is also unanswered. Are they more depressed or in grief from losing gambling in their lives? What have they really lost – getting high or shame (plus debt, angry families, loss of a job, debt, etc.) after losing? Or are they relieved and demonstrate increasede capacity to relate to close others in their lives?

Thanks again.