Psychological trauma has adverse consequences for the body as well as the mind. Some research suggests that the way we cope influences how psychological trauma influences physical health (Lawler et al., 2005). This week’s DRAM reviews a study examining how avoidant coping and drinking mediate the relationship between sexual trauma and physical complaints (Bedard-Gilligan, Cronce, Lehavot, Blayney, & Kaysen, 2013).

Methods

- Researchers contacted a large random sample of female students at northwestern university.

- Eligible participants reported recent “heavy episodic drinking”[1]. The researchers selected 722 who had experienced “at least one unwanted sexual experience” and 105 controls who reported no traumatic experiences.

- The study included questions about the following concepts:

- Trauma history, including questionnaires on sexual experiences, childhood victimization, and traumatic life experiences.[2]

- Past month PTSD symptoms asking about degree of distress relating to “worst unwanted sexual experience or most stressful life experience.”[3]

- Avoidant coping (e.g. I’ve been giving up trying to deal with it), excluding coping through substance use.[4]

- Physical health complaints (e.g., headaches, watery eyes, sore muscles).[5]

- Drinks per week.[6]

- Based on responses these measures, the researchers divided participants into three groups:

- sexual assault but no PTSD (no PTSD; n = 580)

- sexual assault with PTSD (PTSD; n = 142)

- no trauma (noTRM; n=105)

Results

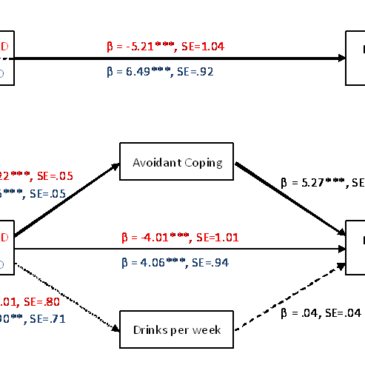

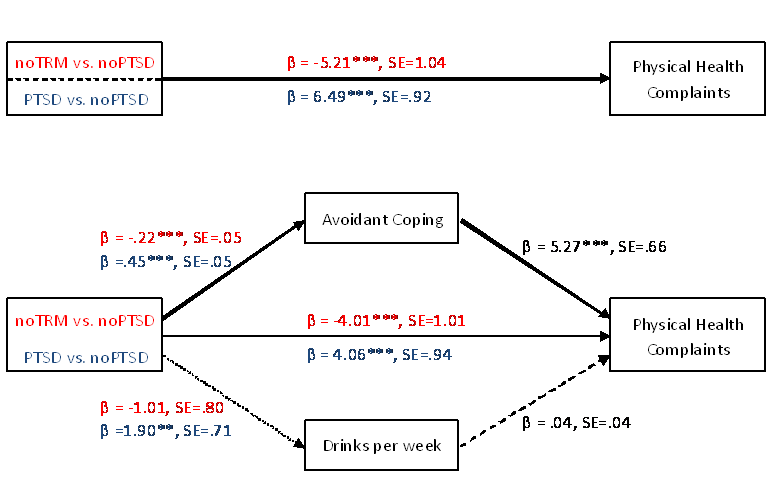

- The top part of the Figure shows the analysis examining whether there was a direct relationship between trauma group and physical complaints.

- As indicated by the beta of -5.21, being in the noTRM group (i.e., not experiencing trauma) was related to a decrease in physical health complaints as compared to the noPTSD group.

- As indicated by the beta of 6.49, being in the PTSD group was related to an increase in physical health complains, as compared to the no PTSD group.

- The bottom part of the Figure shows the analysis examining if the relationship between trauma group and physical complaints was mediated by avoidant coping and/or drinking behaviors. The figure illustrates several findings:

- Trauma group was related to both avoidant coping and drinks per week, such that those with PTSD were using avoidant coping strategies more frequently and drank more heavily than the other groups.

- When avoidant coping was included in the model, the relationship between trauma group and physical health complaints was diminished. This was true for both group comparisons: for noTRM vs. noPTSD, the beta changes from -5.21 to -4.01 when avoidant coping is included in the model, and for noPTSD vs. PTSD, the beta changes from 6.49 to 4.06.

- However, drinking behaviors did not help account for the relationship between trauma group and physical health complaints (change in betas not shown).

Figure. Mediation model adapted from Bedard-Gilligan et al., 2013. Note: Typeface of line indicates strength of effect. Red coefficients pertain to noTRM vs. no PTSD comparison; blue coefficients pertain to PTSD vs. noPTSD comparison. ***p < .001; **p < .01. Click image to enlarge.

Limitations

- This study only assessed female college students who were heavy drinkers and only one type of psychological trauma (i.e., sexual abuse), and had a low response rate (37%), so generalizability to other groups of people is limited.

- These data were retrospective in nature and collected via self-report, making them vulnerable to recall and self-report biases.

- Because the study was cross-sectional, we cannot draw any causal conclusions about the relationships among the variables.

Conclusions

These results indicate that PTSD is associated with more physical complaints, drinking, and avoidant coping strategies. It would seem intuitive that individuals who are self-medicating their emotional pain would experience physical health complaints due to their drinking. This study, however, suggests that avoidant coping (measured in a way that excludes substance use behaviors) is in fact a stronger explanation for the link between trauma/PTSD and the experience of physical health complaints than drinking. Both the trauma itself, and the PTSD symptoms over and above the trauma alone, appear to increase risk for an avoidant coping pattern of behavior that might in turn create physical health problems. There should be easy access to interventions which help survivors address underlying coping processes, possibly through Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, to help, eventually, alleviate both mental and physical distress.

-Emily Shoov

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

References

Bedard-Gilligan, M., Cronce, J.M., Lehavot, K., Blayney, J.A., & Kaysen, D. (2013) The Relationship Between Assault and Physical Health Complaints in a Sample of Female Drinkers: Roles of Avoidant Coping and Alcohol Use. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. DOI: 10.1177/0886260513507139

Carver, C. S. (1997). You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the brief COPE. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 4(1), 92-100.

Collins, R., Parks, G. A., & Marlatt, G. (1985). Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the selfadministration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53(2), 189-200.

Finkelhor, D. (1979). What’s wrong with sex between adults and children? Ethics and the problem of sexual abuse. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 49(4), 692-697

Foa, E. B., Cashman, L., Jaycox, L., & Perry, K. (1997). The validation of a self report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder: The Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale. Psychological Assessment, 9(4), 445-451.

Koss, M. P., & Oros, C. J. (1982). Sexual Experiences Survey: A research instrument investigating sexual aggression and victimization. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 50(3), 455-457.

Kubany, E. S., Leisen, M., Kaplan, A. S., Watson, S. B., Haynes, S. N., Owens, J. A., & Burns, K. (2000). Development and preliminary validation of a brief broadspectrum measure of trauma exposure: The Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment, 12(2), 210-224.

Lawler, C., Ouimette, P., & Dahlstedt, D. (2005). Posttraumatic stress symptoms, coping, and physical health status among university students seeking health care. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 18(6), 741-750.

Pennebaker, J. W. (1982). The psychology of physical symptoms. New York, NY: Springer Verlag.