Homeless youth are more likely to have substance-using peers than housed youth (Greene, Ennett, & Ringwalt, 1997). As a result, among homeless youth, peers might tend to reinforce high-risk behaviors, a process known as “deviancy training” (Dishion & Dodge, 2005). However, we know little about which peer characteristics predict shared drinking and drug use among homeless youth, and this information will be important to designing the most effect interventions. Today’s STASH reviews a study examining the characteristics of people with whom homeless youth engage in substance use (Green et al., 2013), as part of our Special Series on Homelessness and Economic Hardship.

Methods

- Participants were 419 homeless youth between the ages of 13 and 24 (63% male), recruited from shelters, drop-in centers, and known street sites in Los Angeles County. Most reported lifetime drinking (92%) and most reported lifetime drug use (93%).

- Participants identified 20 people in their social networks (i.e., alters) and described each alter in terms of several characteristics, including the following:

- Alter characteristics, such as gender, employment, housing status, whether they provided the participant with social support, whether they were influential,1 and whether they were popular.2

- Dyadic characteristics, including whether the participant consumed alcohol or used drugs with the alter during the past 3 months.

- The researchers explored which alter characteristics were associated with shared drinking and shared drug use, among other research questions.

Results

-

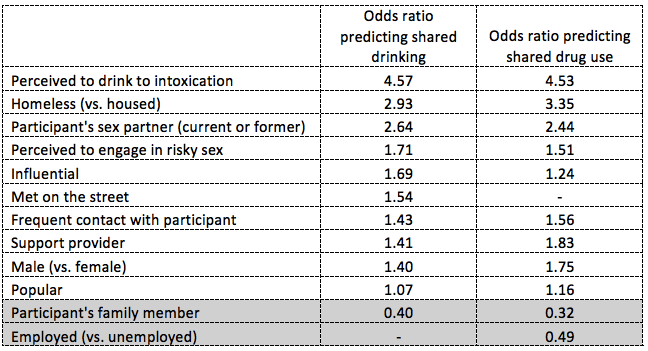

Shared drinking was more likely with social network alters who were male, homeless, a sex partner, a support provider, who was more influential, and with whom the participant had frequent contact, among other factors (Table 1). On other hand, participants were less likely to drink with family members.

-

Predictors of shared drug use were largely similar, as Table 1 illustrates. Participants were also less likely to use drugs with an alter who was employed part- or full-time.

Limitations

- These data were collected with a sample of homeless participants with high rates of lifetime drug and alcohol use. It is unclear whether the same patterns will occur for other young people.

- Researchers relied on participants’ perceptions of the alters, rather than asking the alters to describe themselves directly.

- The outcome was a straightforward yes/no indicating any shared substance use in the past 3 months. It might be interesting to examine the frequency of shared substance use in a more fine-grained way.

Conclusions

Several social network member characteristics predicted shared substance use among homeless youth. Results suggest that homeless youth are most likely to engage in substance use with other homeless youth whom they met on the street and who engage in their own risky behaviors, are sex partners, are frequently available, and are seen as influential and supportive. These groups of peers might be most likely to encourage substance use and other forms of deviancy training. However, other research indicates that homeless adolescents maintain contact with their home-based peers, who are less likely to misuse substances, via social networking (Rice, Milburn, & Monro, 2011). Healthcare workers might try to strengthen homeless youths’ ties with family members and with home-based peers, so that these peers become more available, influential, and supportive.

—Heather Gray

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

References

Campbell, R., Starkey, F., Holliday, J., Audrey, S., Bloor, M., Parry-Langdon, N., . . . Moore, L. (2008). An informal school-based peer-led intervention for smoking prevention in adolescence (ASSIST): a cluster randomised trial. Lancet, 371(9624), 1595-1602. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60692-3

Dishion, T. J., & Dodge, K. A. (2005). Peer Contagion in Interventions for Children and Adolescents: Moving Towards an Understanding of the Ecology and Dynamics of Change. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33(3), 395-400. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-3579-z

Green, H. D., Jr., de la Haye, K., Tucker, J. S., & Golinelli, D. (2013). Shared risk: Who engages in substance use with American homeless youth? Addiction, 108(9), 1618-1624. doi: 10.1111/add.12177

Greene, J. M., Ennett, S. T., & Ringwalt, C. L. (1997). Substance use among runaway and homeless youth in three national samples. American Journal of Public Health, 87, 229-235.

Rice, E., Milburn, N. G., & Monro, W. (2011). Social networking technology, social network composition, and reductions in substance use among homeless adolescents. Prevention Science, 12(1), 80-88. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0191-4

Roy, É., Haley, N., Leclerc, P., Cédras, L., & Boivin, J.-F. (2002). Drug injection among street youth: The first time. Addiction, 97(8), 1003-1009. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00161.x

________________

[1] The alters’ status as influential was measured on a continuum from 1-3, according to how many of the following characteristics they met: among the core group of people with whom the alter hung out; someone whose opinion mattered a great deal to the participant; and someone who was viewed as a leader or role model by the community.

[2] Popularity was defined as the number of relationships an alter shared with other people within the participant’s social network.