Although everyone experiences distressing events from time to time, people differ in their distress tolerance – that is, their ability to endure painful reactions to distressing events. People who are low in distress tolerance often turn to alcohol or other substances to cope with negative affect. Although this tendency is fairly well understood, less is known about what happens to negative affect after people drink. In other words, to what extent does a heavy drinking episode reduce subsequent negative affect, and does distress tolerance moderate this effect? This week, The DRAM reviews a study by Matison W. McCool and colleagues that explored these and other questions.

What were the research questions?

(1) Is there evidence of affective relief, such that heavy drinking temporarily alleviates negative affect, and (2) is this especially true for people with low distress tolerance?

What did the researchers do?

From July 2020 to July 2021, the researchers used online ads to recruit participants for a broader study on the impact of COVID-19 on mental health and substance use. All participants were 21+, lived in Colorado, and reported at least weekly alcohol or cannabis use. Forty-one participants were included in the analyses for this study. The researchers administered a baseline measure of distress tolerance and then prompted participants to complete a brief online survey about their drinking, negative affect, and other topics four times a day for 60 days. This approach to repeated daily measurements is called ecological momentary assessment (EMA).

What did they find?

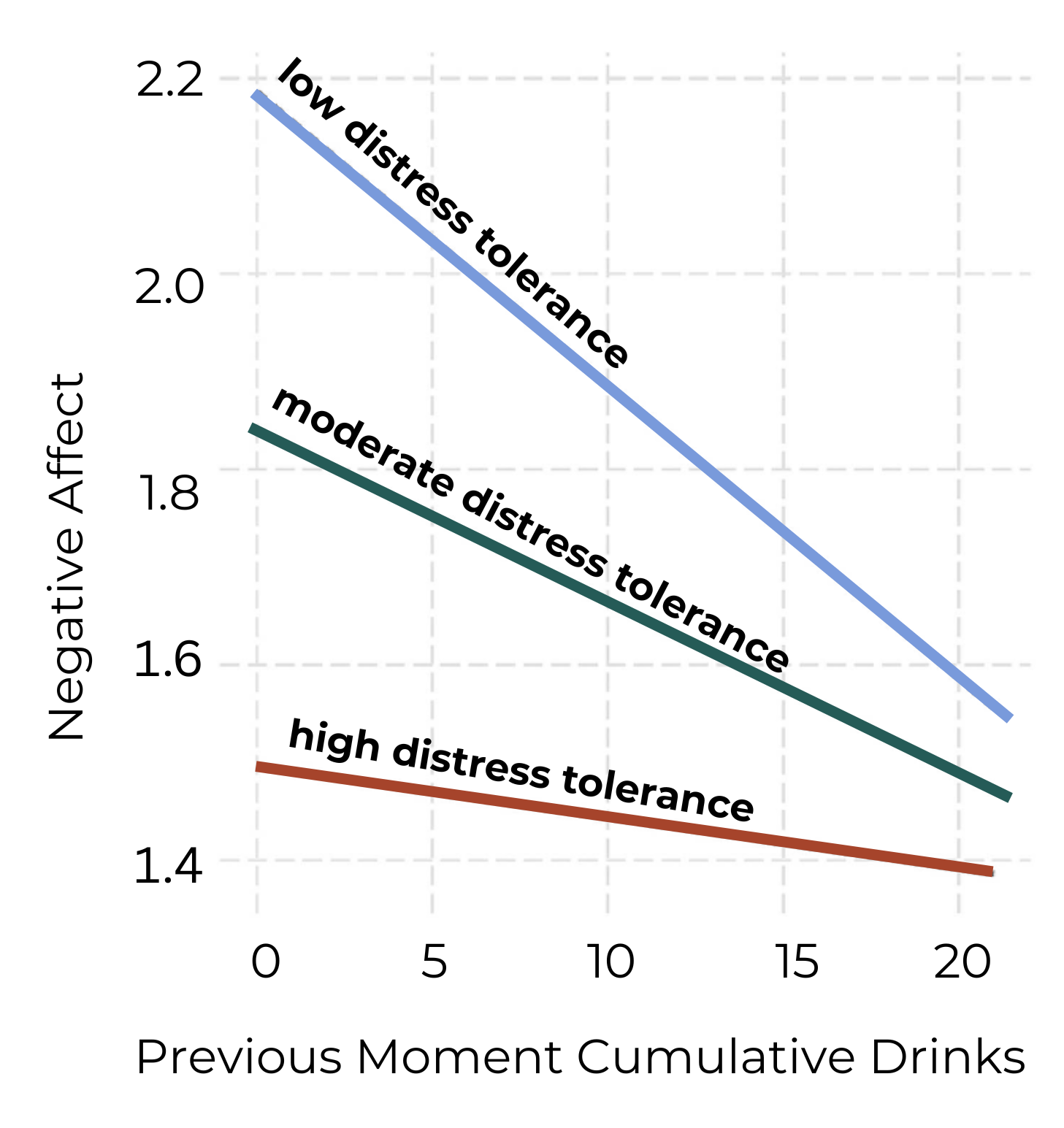

The more drinks a participant consumed during a drinking episode, the lower their negative affect during the subsequent assessment. This effect was moderated by distress tolerance. Among participants relatively low in the ability to tolerate distress, consuming more drinks predicted less subsequent negative affect. In other words, they experienced affective relief by drinking. Among participants who were moderate or high in distress tolerance, there was no detectable relationship between the number of drinks they consumed and their subsequent negative affect (see Figure).

Figure. Cumulative drinks and subsequent negative affect as a function of distress tolerance. Recreated from McCool et al., 2025. Click image to enlarge.

Why do these findings matter?

When it comes to preventing or treating addiction, knowing what a substance does for a person is as important as knowing what they do to a person. The results from this study support the negative reinforcement pathway of alcohol on negative affect: drinking becomes a preferred coping strategy because it temporarily reduces unpleasant feelings. Unfortunately, this could lead to life-altering consequences, including increased alcohol intake over time and the possible development of an alcohol use disorder (AUD). Some AUD treatment approaches, such as dialectical behavior therapy, specifically aim to increase the patient’s distress tolerance, and clinicians should consider suggesting this approach for clients who have this particular vulnerability.

Every study has limitations. What are the limitations in this study?

The researchers took a general approach to measuring negative affect and did not measure specific types of unpleasant feelings, such as sadness, anxiety, or anger. These feelings might have unique relationships with drinking and distress tolerance. Additionally, they only measured distress tolerance at baseline and treated it as a stable characteristic, but measuring it moment-to-moment might have produced different results. Finally, it is unclear how clinically significant the observed reductions in negative affect might be.

For more information:

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism has tips and resources for people struggling with problem drinking. For additional drinking self-help tools, please visit our Addiction Resources page.

— Heather Gray, PhD

Want CE credit for reading BASIS articles? Click here to visit our Courses Website and access our free online courses.