Incarcerated people in the United States experience a host of poor health outcomes, such as chronic diseases including addiction and mental illness. The rate of tobacco use in particular, which is triple that of the general population, is a major public health concern for the criminal justice system (Vaughn & del Carmen, 1993). Because of the well-documented negative health consequences of smoking, administrators have prohibited tobacco sales and use in a majority of US correctional facilities. In this week’s ASHES, as part of our Special Series on Addiction within Correctional Facilities, we review a study by Dickert and colleagues that examined the impact on inmate mortality rates of a reduction and eventual ban of tobacco products in the New Jersey Department of Corrections (NJDOC).

Methods

- NJDOC reduced the sale of tobacco products in its facilities by almost 50% between 2009 and 2011. They introduced smoking cessation programs and sold nicotine lozenges in the prison commissaries during this same time period. NJDOC officially banned the sale and use of tobacco products on prison grounds, including facility grounds in February 2013.

- About 23,000 inmates are held in 13 state prisons run by the NJDOC at any one time. Upon arrival, every inmate undergoes a mental health assessment. Those diagnosed with a mental disorder (using DSM-IV criteria) that may impede their ability to function in a prison setting are identified as persons with special need for mental health care, and constitute about 13% of the total prison population.

- Researchers tracked mortality rates semi-annually from 2005 through the first half of 2014, both in the total inmate population and in the special mental health (MH) needs population.

Results

- Annual mortality rates for persons with special MH needs were about three times higher than those for individuals without special MH needs.

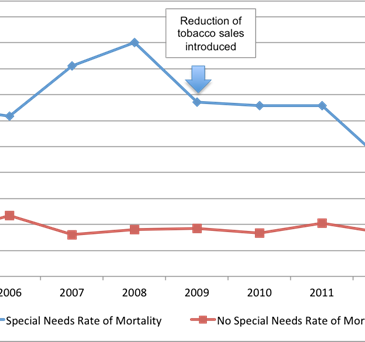

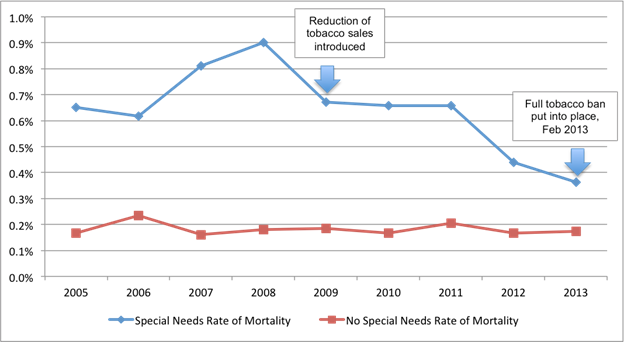

- As the Figure shows:

- The special MH needs population had higher mortality rates across all years than the rest of the population.

- The annual mortality rate for all inmates decreased by 13% from 2005 to 2013.

- The mortality rate for prisoners identified to have special MH needs decreased by 48% over the same time period.

- Researchers performed a statistical analysis of the correlation between tobacco sales per inmate and mortality rate for the prison populations with and without special MH needs. For inmates with special MH needs, the reduction of tobacco sales was associated with a reduction in mortality rates. This association was not statistically significant for their counterparts without special MH needs.

Figure 1: The mortality rates of the total NJDOC population and those classified as having or not having special MH needs over the course of a reduction and eventual elimination of tobacco sales and use (adapted from Dickert et al., 2015).

Limitations

- This sample included only NJDOC inmates. The findings might not generalize to the incarcerated population of other states or outside the US.

- The researchers used an aggregate database to calculate and analyze mortality in the NJDOC prison population, therefore not utilizing individual inmate data. In future analysis, it will be important to use this individual inmate data to explore the role of variables other than mental health needs, like length of sentence, chronic disease status, etc.

- While the total population studied was large (about 23,000), the annual deaths were low in comparison (average of 61 inmates per year) and varied greatly on a semi-annual basis.

Conclusion

A reduction and eventual ban of tobacco sales and use was correlated with a 48% reduction in mortality among inmates with special needs for mental health care. These mortality rates declined across time despite the aging population of NJDOC inmates (7.4% to 13.8% of the population was 50+ from 2005 to 2013). While the majority of correctional facilities in the country have implemented smoke-free policies, these findings might provide additional incentive for the few institutions that have not adopted these policies. It is also possible these findings could spur tobacco-free policies in other settings that serve a sub-population with mental illness, such as out-patient or in-patient substance use and mental health treatment.

— Layne Keating

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.