The American Psychiatric Association’s (2013) fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5) suggests a variety of changes for the way professionals diagnose Gambling Disorder (GD). For instance, the scoring threshold for GD has been cut from 5 to 4, and one of the ten criteria, “illegal acts,”1 has been eliminated. This week, as a part of our Special Series on Addiction Treatment in Correctional Facilities, The WAGER reviews a study that examined the impact of these changes on diagnostic criteria upon diagnosis patterns amongst incarcerated people (Turner, Stinchfield, McCready, McAvoy, & Ferentzy, 2015).

Methods

- The researchers recruited 676 incarcerated participants from 11 different correctional institutions in Ontario, Canada.

- Researchers used a questionnaire packet that included the following instruments:

- Two measures of gambling problems (i.e., South Oaks Gambling Screen – SOGS (Lesieur and Blume 1987) and the Problem Gambling Severity Index – PGSI (Ferris and Wayne 2001)

- Questions assessing all ten DSM-IV Criteria (Turner et al. 2006, 2008)

- A measure of harmful consequences of gambling (e.g., “Has gambling caused you any problems with your social relationships?”) (Turner et al. 2006, 2008)

- A questionnaire that asked about the frequency of play across 16 different types of gambling.

- These measures ask questions relevant to gambling habits prior to incarceration and assess the severity of the disorder.

- Researchers used a questionnaire packet that included the following instruments:

- The researchers compared how diagnosis patterns change with the changes from the DSM-IV to the DSM-5.

Results

- Using the DSM-IV definition, about 7.4% of the prisoner sample met criteria for Pathological Gambling; however, using a cut score of four rather than five, the DSM-IV definition identified about 9.3% of prisoners as having Gambling Disorder.

- Few participants (5.9%) endorsed the illegal acts criterion, even among a prison sample. Removing the Illegal acts criterion reduced the number of participants identified as having a Gambling Disorder from 69 to 63.

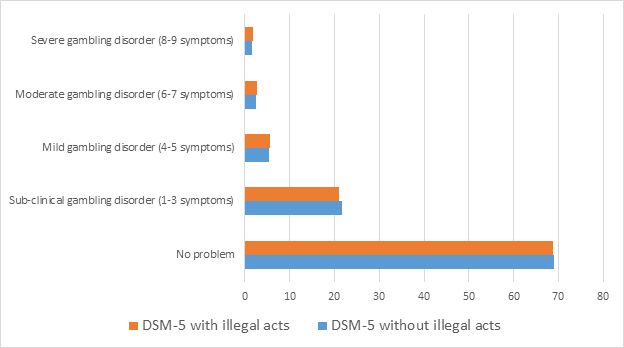

- The authors grouped participants into categories of Gambling Disorder severity, based on the number of symptoms they endorsed. The proportion of participants in the Mild, Moderate, and Severe Gambling Disorder groups decreased slightly with the removal of the illegal acts criterion (Figure).

- A regression analysis indicated that three DSM-IV criteria, including the illegal acts criterion, significantly related to all four measures of gambling and gambling-related problems (i.e., SOGS, CPGI/PGSI, harmful consequences of gambling, and gambling frequency). This suggests that asking clients whether they’ve engaged in illegal acts to support their gambling might be especially helpful in understanding the severity of the gambling problem.

Figure. Proportion of participants at each Gambling Disorder scoring level, with and without the illegal acts criterion. Click image to enlarge.

Limitations

- Researchers did not use an actual DSM5 questionnaire in their survey materials, and instead estimated what the DSM5 scores would result in based upon applying the DSM5 algorithm to prisoners’ answers to the DSM-IV questionnaire.

- The study does not ask questions about current gambling habits, which would allow researchers to compare past and present habits, and observe their habits in a correctional setting.

- The data collected consisted of self-report data of participants who may have been incarcerated for offenses that include duplicity, such as fraud.

Conclusion

The results indicate that the changes in the diagnostic criteria of GD might affect rates of diagnosis among incarcerated people. When the illegal act criterion was removed, the number of offenders identified with gambling disorder decreased slightly; this might represent misdiagnosis/false negatives. However, the reduction of the cut point from 5 to 4 symptoms increased the rate of diagnosis. In summary, the authors suggest that researchers and clinicians interested in diagnosing GD among incarcerated people use the DSM-5 criteria but subsume illegal acts into another criterion, “lying to others.”

–Alec Conte

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

References

Turner, N. E., Stinchfield, R., McCready, J., McAvoy, S., & Ferentzy, P. (2015). Endorsement of Criminal Behavior Amongst Offenders: Implications for DSM-5 Gambling Disorder. Journal of Gambling Studies, 31(1). doi: 10.1007/s10899-015-9540-3

Turner, N. E., Jain, U., Spence, W., & Zangeneh, M. (2008). Pathways to pathological gambling: Component analysis of variables related to pathological gambling. International Gambling Studies, 8(3), 281–298.

Turner, N. E., Littman-Sharp, N., & Zangeneh, M. (2006). The experience of gambling and its role in problem gambling. International Gambling Studies, 6, 237–266.

[1] The illegal acts criterion states, “have committed illegal acts such as forgery, fraud, theft or other embezzlement in order to finance your gambling”

Nicholas F Giso October 18, 2015

amazing research , well written.

Nicholas F Giso

nickmaryma@ aol.com