Most advertisers use a wide variety of promotions and ad types, because different people react more or react less to different kinds of ads. Some people, for example, notice product and logo placement more than others. Other people are more susceptible to jingles and earworms. Accordingly, gambling service providers have invested millions of dollars in many different forms of advertising, from jerseys to stadium walls to 30-second spots on television broadcasts. This week, as a part of our Special Series on Addiction and Sports, The WAGER will review a study exploring gamblers’ reactions to different kinds of promotions and advertising (Hing et al., 2015).

Methods

- The researchers purchased a research panel from a market research company and recruited 544 sports bettors from Queensland, Australia who were each at least 18 years old.

- The researchers used the Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI) (Ferris & Wynne, 2001) to classify the participants as non-problem gamblers, low risk gamblers, moderate risk gamblers, or problem gamblers.

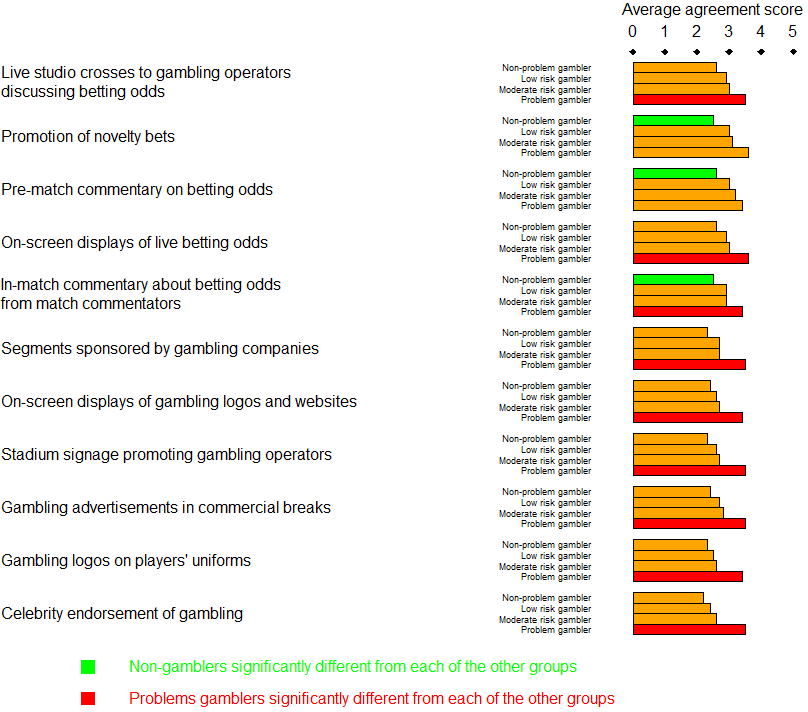

- The researchers measured participants’ sense that they are influenced by different types of promotions. For each of eleven classes of promotions (e.g., stadium signage, celebrity endorsements) participants answered “How much do you agree or disagree that the following gambling promotions encourage you to bet on the sports where gambling is promoted?”) using a 5-category Likert scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree).

- For each of the eleven classes of promotions, the researchers calculated the average agreement scores for the non-problem gamblers, low risk gamblers, moderate risk gamblers, and problem gamblers.

- The researchers compared agreement ratings among participants in different groups. Specifically, they used ANOVAs and Tukey’s HSD.

Results

- Just over half (50.2%; n = 273) of participants were classified as non-problem gamblers, 17.8% (n = 97) were classified as low risk gamblers, 9.9% (n = 54) were classified as moderate risk gamblers, and 22.1% (n = 120) were classified as problem gamblers.

- In nine out of the eleven classes of promotions, the problem gamblers had significantly higher agreement scores than the other three groups.

- When asked about promotion of novelty bets, pre-match commentary on betting odds, and in-match commentary on betting odds, the non-problem gamblers had significantly lower agreement scores than the other three groups.

Figure. Average agreement scores for each of the four groups of gamblers. Participants were asked “How much do you agree or disagree that the following gambling promotions encourage you to bet on the sports where gambling is promoted?” Click image to enlarge.

Limitations

- The study relied on self-reported reactions to advertising. The participants may have misrepresented past reactions, either due to social desirability bias or limited recollection of previous events, or they might have difficultly assessing their reactions to the advertisements.

- Whereas the question referred to “encourage[ment]… to bet”, it did not say anything about actual changes in betting behavior. It is unknown whether the advertisements actually led to additional bets or larger bet sizes.

- The recruitment was limited to Queensland, Australia. The results may not generalize to other localities with different sports fandoms and different gambling markets.

Conclusion

In this study, Hing and her colleagues observed that problem gamblers felt more encouragement to bet from the promotions and ads than other gamblers. They also observed that the non-problem gamblers responded less favorably to direct commentary on gambling odds. The former result is important because it speaks to how vigilant recovering pathological gamblers need to be around sports fandom and associated media. The latter result is interesting because it could mean that non-problem gamblers are less likely to respond to recommendations from “experts” or in-depth analyses of the athletes. It might mean that non-problem gamblers are less likely to “chase value” or view sports betting as a way to make money. Overall, how gamblers respond to advertising my give researchers clues as to their reasons for and mentality when gambling.

— Matthew Tom

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

References

Ferris, J., & Wynne, H. (2001). The Canadian Problem Gambling Index: Final Report. Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse.

Hing, N., Lamont, M., Vitartas, P., & Fink, E. (2015). Sports bettors’ responses to sports-embedded gambling promotions: Implications for compulsive consumption. Journal of Business Research, 68(10), 2057–2066.