All 50 states require convicted repeat, and in some cases first-time DUI offenders to install ignition interlock devices (IIDs). These devices require drivers to breathe into them and allow the car to start only if the driver’s breath alcohol concentration is below the programmed limit. IIDs are very effective at reducing DUI recidivism while they are installed (Voas et al., 1999). However, offenders often return to drunk driving once their IIDs are removed (e.g., Marques, Voas, Roth, & Tippetts, 2010). One potential explanation for this problem is that some DUI offenders are unable or unwilling to change their broader drinking patterns, including their tendency to drink outside the home with friends.This week’s edition of The DRAM reviews a study that investigated what distinguishes DUI offenders who change their drinking patterns in order to adapt to IIDs from those who do not (Beck, Kelley-Baker, & Voas, 2015).

Methods

- 150 DUI offenders who were part of an ignition interlock program completed a web-based survey about their drinking behaviors and contexts, and perceptions of outcomes.

- Only offenders who reported drinking primarily in bars and restaurants before installing their IID were selected for this study.

- Based on their responses, the offenders were separated into two groups:

- Adapters – those who changed their drinking environment, so that they no longer drank primarily in bars and restaurants; and

- Nonadapters – those who continued drinking primarily in bars and restaurants.

- The two groups did not differ on any demographic characteristics or measures prior to installation of the interlock device. For instance, they reported roughly the same number of drinks per drinking occasion.

- The researchers examined how Adapters and Nonadapters differed in terms of their drinking patterns and beliefs after IID installation.

Results

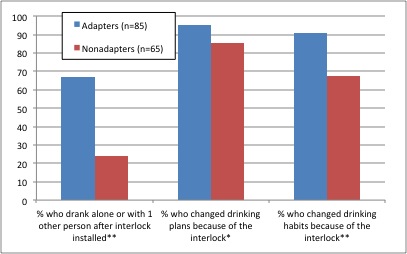

- Though Adapters and Nonadapters were largely similar before IID installation, they differed from each other after installation, in a number of ways (See Figure1):

- Compared to Nonadapters, Adapters reported fewer drinks per occasion (M=2.62 vs M=4.05), higher likelihood of drinking alone or only with a significant other (rather than in a group), and higher likelihood of changing drinking habits (e.g. making a plan before drinking in order to avoid driving afterwards).

- Adapters were also significantly more likely than Nonadapters to think of the interlock device as a “reminder that [they] need to limit [their] drinking to avoid another DUI/DWI” (58.5% vs 40%).

Figure 1. Drinking behaviors of Adapters vs Nonadapters, adapted from Beck et al. (2014). (*p<. 05, ** p<.001).

Limitations

- Self-report online survey measures are not always a reliable source of information about behaviors and intentions because of self-report bias.

- Most participants were from a metropolitan area in Phoenix Arizona; results might not be generalizable to all ignition interlock users.

- The design does not allow us to determine whether Adapters persisted in their changed behavior after removal of the IID.

Conclusion

Research has shown that DUI programs are particularly effective when they train individuals to separate the act of driving from that of drinking (Rider et al., 2006; Rider et al., 2007). The primary finding of this study is that ignition interlock users who alter their drinking environments in response to an IID (Adapters) seem to be more receptive to changing other aspects of their drinking behavior, as well —they shift to drinking at home, alone or with a significant other, rather than outside the home. Those who are unable or unwilling to alter their drinking environment also fail to make a host of other changes to their drinking. Identifying which offenders are unlikely to change their drinking environments could help specify those in need of further intervention. Follow-up work should study the drinking and driving behaviors of these two clusters of individuals after IID removal.

– Emily Shoov

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

References

Marques, P. R., Voas, R. B., Roth, R., & Tippetts, A. S. Evaluation of the New Mexico Ignition Interlock Program. Washington, DC: US Department of Transportation, NHTSA; 2010. DOT HS 811 410.

Rider, R., Kelley-Baker, T., Voas, R., Murphy, B., McKnight, A.J., & Levings, C. (2006). The impact of a novel educational curriculum for first-time DUI offenders on intermediate outcomes relevant to DUI recidivism. Accident Analalysis & Prevention, 38, 482-489.

Rider. R. P., Voas, R. B., Kelley-Baker, T., Grosz, M., & Murphy, B. (2007). Preventing alcohol-related convictions: The impact of a novel curriculum for first-time offenders on DUI recidivism. Traffic Injury Prevention, 8(2) 147-152.

Voas, R. B., Marques, P. R., Tippetts, A. S., & Beirness, D. J. (1999). The Alberta Interlock Program: The evaluation of a province-wide program on DUI recidivism. Addiction, 94, 1849-1859.