During the Great Recession of 2007-2009, the unemployment rate in the United States doubled from just under 5% during 2007 up to a high of 10% during 2009 (Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), 2013). It is unclear how economic hardship affects drinking behaviors (Catalano, Dooley, & Wilson, 1993; Ruhm & Black, 2002). This week the DRAM reviews a study that attempts to shed some light upon this issue by examining drinking habits in the US changed during the recent recession (Bor, Basu, Coutts et al., 2013), as part of our Special Series on Homelessness and Economic Hardship.

Methods

- Researchers used data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), a monthly, nationally representative, landline telephone survey of men and women aged 18 or older (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013).

- The study included data from 2006-2007 (pre-recession, n=773,290) and from 2008-2009 (recession, n=832,839)

- The survey included data on demographic factors and substance use, as well as other domains

- Alcohol use questions included monthly drinking days and average number of drinks consumed on drinking days.

- Frequent binge drinking was defined as four or more binge drinking episodes in a month.

- A binge drinking episode was defined as a day when an individual had 4+ (for women) or 5+ (for men) drinks on a single occasion

- Researchers ran comparisons between 06/07 data and 08/09 data while controlling for variables such as age, sex, race, and education. In order to determine whether behavioral changes could be explained by income loss or unemployment, they also ran these comparisons while controlling for income and employment status.

Results

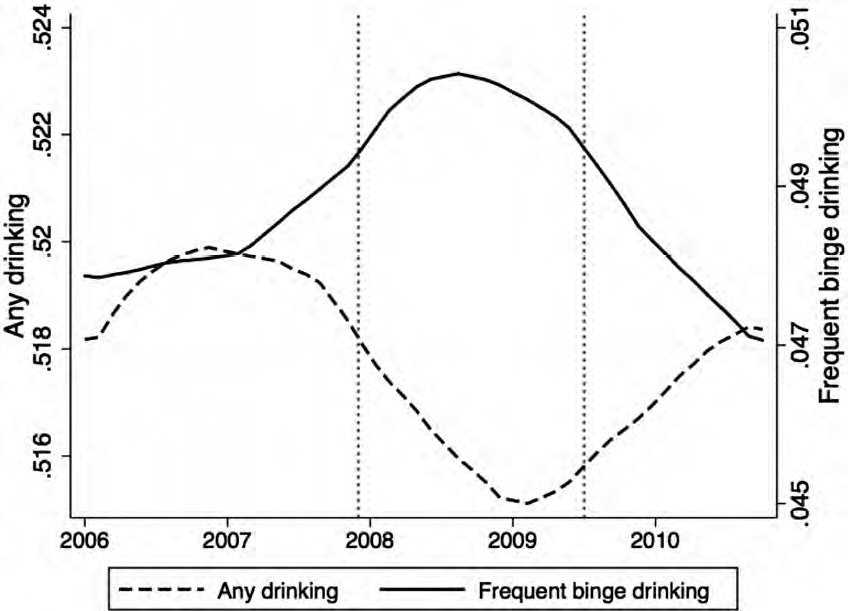

- The percentage of people drinking, that is individuals who had any drinks in the past 30 days, dropped during the recession (marked by the dotted line), but the frequency of binge drinking among the entire recession sample rose (see Figure).

- The inclusion of income and employment data did not alter the results: those who lost income or experienced unemployment similar drinking behaviors compared to those who did not.

Figure. Drinking behaviors before and during the Great Recession (reprinted from Bor et al. 2012 with permission from Oxford Journals). Click image to enlarge.

Limitations

- The survey does not include longitudinal data on individuals; rather, it presents a cross-sectional “snapshot” in time. As a result, it is difficult to determine behavioral change on an individual level.

- Land-line only telephone surveys can suffer from a sampling bias.

- The survey uses self-report data for alcohol use, which is subject to well-known limitations.

Conclusions

This finding suggests that people who were surveyed during the recession were more likely to abstain from drinking than those surveyed before the recession, but those who did drink during the recession tended to drink more heavily. This suggests that there are two different factors at play. Previous research has proposed an “income-effect” which suggests that lower income translates into a lesser means to purchase alcohol (Ruhm & Black, 2002), which might be operating among the people who chose not to drink at all. Additionally, a “provocation” effect has been proposed that suggests that individuals who do drink might drink more because they turn to alcohol to cope with job insecurity or financial stress (Catalano, 1997). The fact that the results are still significant after controlling for income and employment status suggests that factors other than an individual’s immediate financial state (e.g., anxiety about potential job loss) might be involved, and that further research is necessary to uncover these factors.

-Jed Jeng

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

References

Bor, J., Basu, S., Coutts, A., McKee, M., & Stuckler, D. (2013). Alcohol Use During the Great Recession of 2008-2009. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 48(3), 343-348.

Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). (2013). Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey. from http://data.bls.gov/timeseries/LNS14000000

Catalano, R. (1997). An emerging theory of the effect of economic contraction on alcohol abuse in the United States. Social Justice Research, 10(2), 191-201.

Catalano, R., Dooley, D., & Wilson, G. (1993). Job loss and alcohol abuse: a test using data from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area project. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 34, 215-225.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. from http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/index.htm

Ruhm, C., & Black, W. (2002). Does drinking really decrease in bad times? Journal of Health Economics, 21(4), 659-678.