Animal models of human behavior help scientists to understand pathology and develop new drugs. This week’s The WAGER reviews a study that examines an animal model of gambling behavior (Zeeb, Robbins, & Winstanley, 2009). Zeeb et al. sought to determine if rats are capable of “playing the odds” and if altering their brain chemistry (e.g., to mimic the neurochemistry of human gamblers) changes the rats’ decision-making, which according to the authors was a proxy for gambling strategy.

Method

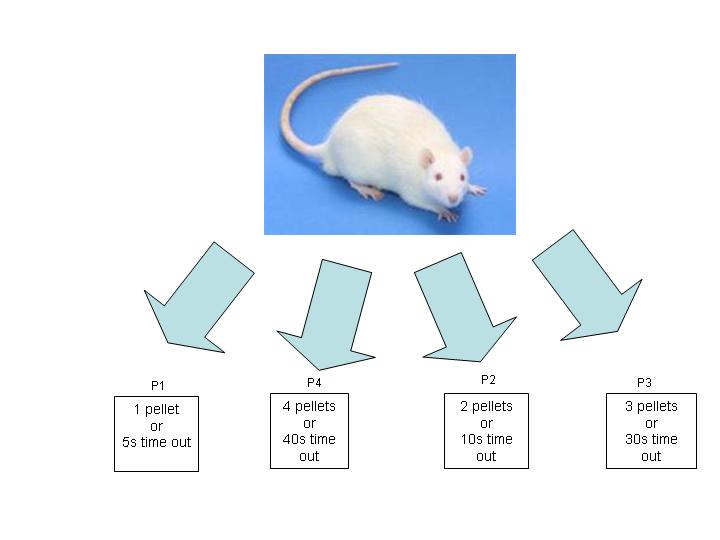

- Investigators trained rats (N = 32) to choose between four trays (P1 – 4) to nose-poke for food (see Figure 1).

-

- Each time a rat “won”, it received one or more sugar pellets as a reward.

- Each time it “lost”, there was a timeout during which it could not play.

- In terms of long-term gain, the optimal choice was to choose P2, which was getting 2 sugar pellets with moderate waiting time.

- P1 represented the choice with the lowest reward (1 pellet) and the lowest probability of timeout; P4 was the choice with the highest reward (4 pellets) and the highest probability of timeout.

- After at least one week of stable baseline behavior, the researchers injected various drugs that affected (i.e., increased or decreased) the level of dopamine in brain to alter the animals' brain chemistry to mimic that of problem gamblers. Examples of drugs are:

-

- Amphetamine:

potentially increases the level of dopamine in the brain. - Eticlopride:

blocks dopamine receptors. - SKF

81297: triggers dopamine response by the brain cell.

- Amphetamine:

- Investigators conducted repeated measures ANOVA to measure how the preferences were changed following the drug injection.

Figure 1. Trial structure for the Rat Gambling Task.*

Notes:* The location of the trays was counterbalanced across rats. A picture represents one possible setting.

Results

- At baseline, animals consistently showed a preference for the optimal choice (P2), associated with a modest gain and moderate punishment.

- Amphetamine significantly increased selection of the non-optimal choice P1 (p < .01), which is associated with the least punishment but also with the least reward.

- Eticlopride significantly increased selection of the optimal choice (p < .01).

- SKF 81297 significantly increased the selection of P4 (risky with largest probability of punishment) and significantly decreased the selection of the optimal choice (p < .01).

Limitations

- The "Rat gambling task" is not a complete analogy for human gambling behavior (e.g., rats cannot really “lose” food).

- The "decision making" task is not necessarily a proxy for gambling.

- It is not clear if dopamine leads to the avoidance of punishment or awareness of rewards.

- It is not clear if rats are relying on memory to make their choice, rather than basing their preference on the perception of risk or punishment tolerance.

Conclusion

This study indicates that rats are capable of ‘playing the odds’. Moreover, they seem to be “risk-averse” animals, similar to human beings. The obtained data suggest that changing brain chemistry produces subsequent changes in animals “similar-to-gambling” behavior. Specifically, dopaminergic agents (drugs that influence dopamine activity in brain) can impair or improve gambling performance. The results imply that high levels of dopamine might pre-dispose non-optimal decision making, creating a risk factor for gambling-related problems. The mechanism of dopamine as a risk factor is not yet clear. However, the results are consistent with previous studies that found dopamine treatment to increase gambling drive among human patients (Abler, Hahlbrock, Unrath, Gron, & Kassubek, 2009). Taken together, these findings indicate that the rats gambling task might be a useful tool to study biological aspects of gambling.

-Julia Braverman

What do you think? Please use the comment link below to provide feedback on this article.

References

Abler, B., Hahlbrock, R., Unrath, A., Gron, G., & Kassubek, J. (2009). At-risk for pathological gambling: imaging neural reward processing under chronic dopamine agonists. Brain: A Journal of Neurology, 132(9), 2396-2402.

Zeeb, F. D., Robbins, T. W., & Winstanley, C. A. (2009). Serotonergic and Dopaminergic Modulation of Gambling Behavior as Assessed Using a Novel Rat Gambling Task. Neuropsychopharmacology, 34(10), 2329-2343.

Anne MacIsaac November 20, 2009

I would be interested in studies that address how serotonin levels influence gambling behaviour. From a neuropsychology perspective, I suspect that the combined influence of dopamine and serotonin are powerful in the human brain as they relate to problem gambling behaviour.

Randy Ringaman November 25, 2009

I liked the experiment, but once again “food” appears to be looked upon as the same reward a problem gambler would have with money and the time out representing when the money ran out. I did not see a win percentage for either of the trays and what was the randomization that was used. I recall from my Psch Lab days that once the baseline was established, if we began to make the reward frequency variable, the rats would essentially spend as much time as necessary to achieve the reward.

The experiment may provide some basis for someone who may be at risk early on, but I believe there may be at least one or more dots in this equation other than just serotin and dopamine. At some point, a switch is turned on and there doesn’t seem to be a way of turning it off.

I am not very knowledgable in this particular arena, but I am a recovery compulsive gambler (5+ years. I was being treated for depression during my gambling days with SSRI’s, and as my gambling increased, so did the depression and subsequent need for increased dosages of the SSRI’s. This continued for 18 years.

My belief is that somewhere in our brains, there’s a pain avoidance dot which allows us to minimize the pain by super focusing on the gambling at hand or whatever the choice of pain relief is. I believe our brains are capable of rewiring itself for pain avoidance and developing a path of least resistance. This continues until the pain from the consequences of gambling masks the pain issues we were trying to escape from (knowlingly or not-knowlingly). To escape that pain, I would continue to gamble so as to not think about it. Even an attempted suicide would not stop the desire to gamble for myself. I just wanted to get off the merry-go-round.

I apologize for being so lengthy on this, but if there’s even a shred of something that I’ve said that will help identify a direction or help someone in the future, then I have at least put the effort forth to try.