Disordered gamblers do not typically seek treatment (Slutske, 2006). Therefore, it is important to test brief interventions because these strategies might attract more treatment-seeking gamblers than more extensive treatment. Previous WAGERs (see WAGER 13(5) and 11(9)) have reviewed some of these interventions. This week the WAGER reviews a study examining the efficacy of three types of brief interventions for disordered gamblers (Petry, Weinstock, Ledgerwood, & Morasco, 2008).

Methods:

- Participants (N=180) were recruited using advertisements posted at numerous medical clinics and were eligible for this study if they endorsed > 3 South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS: Lesieur & Blume, 1987) items and wagered at least $100.00 on gambling on at least four occasions within the past two months.

- Participants were randomly assigned to one of four treatment groups:

- Assessment Only Control: a baseline for comparison.

- Brief Advice: 10 minute meeting with a therapist to discuss gambling problems, risks, and ways to avoid risk situations.

- Motivational Enhancement Therapy (MET): 50 minute therapist session including personalized feedback about gambling’s influence on goals and values and a plan to change that influence.

- MET plus Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT): MET session and 3 CBT sessions in which therapists determined gambling triggers and strategies for coping with triggers.

- At baseline, 6 weeks, and 9 months, participants reported past month gambling expenditures and were assessed using the SOGS.

- At each follow-up, participants were classified into one of the following groups based on their SOGS scores and past month gambling expenditure:

- Recovered and Improved (e.g., < 3 SOGS items and/or > 30% decrease in dollars wagered).

- Unchanged (e.g., > 3 SOGS items and < 30% reduction in dollars wagered).

Results:

- Retention across assessments ranged from 83.7-87.5%.

- All groups, including the control group, experienced decreases in gambling.

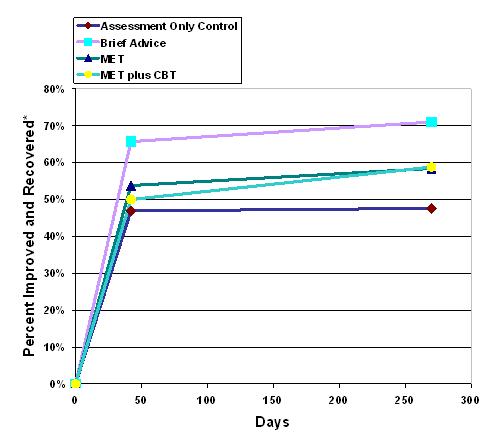

- At 9 months, the only significant difference between pairs of groups was between the best performing group, Brief Advice, and the worst, Assessment Only Control; there were no significant differences among the other groups (See Figure 1).

Figure 1: Percentage of Participants Classified as Improved and Recovered based on Gambling Expenditure and SOGS Score at 6 Weeks and 9 Months (adapted from Petry et al., 2008).

*Recovered and Improved defined as < 3 SOGS items and/or > 30% decrease in dollars wagered. MET- Motivational Enhancement Therapy. CBT- Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy.

Please click on image for a clearer picture, or adjust your browser’s zoom settings.

Limitations:

- This study used self report.

- Recruitment advertisements were located mostly in inner-city clinics making these results difficult to generalize for all populations.

This study indicates that brief interventions can have a positive impact on gambling problems. Surprisingly, the most successful brief intervention was the most brief (e.g., the Brief Advice group). More research about the efficacy and impact of brief interventions for disordered gambling is needed. Brief advice interventions have an advantage over the others because they are cost-efficient and require less investment of therapists’ time.

What do you think? Comments can be addressed to Tasha Chandler.

References:

Lesieur, H. R., & Blume, S. B. (1987). The South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS): A new instrument for the identification of pathological gamblers. American Journal of Psychiatry, 144(9), 1184-1188.

Petry, N. M., Weinstock, J., Ledgerwood, D. M., & Morasco, B. (2008). A randomized trial of brief interventions for problem and pathological gamblers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(2), 318-328.

Slutske, W. S. (2006). Natural recovery and treatment-seeking in pathological gambling: Results of two U.S. national surveys. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163(2), 297-302.

Randy Ringaman April 28, 2016

Hi Tasha. Just read your research article on affectiveness of different treatment/intervention modalities.

Frankly, being a recovering compulsive gambler, I didn’t get much out of this study. The limitations that you recognize, minimize what I think you were hoping to get out of this.

First your criteria for the problem gambler is not very restrictive. Four times at a casino in two months! So called “normal” people would qualify for that. The “SOGS” test is iffy at best.

Secondly, a compulsive or pathological gambler is not going to be honest in that short a period of time with a counselor. Even when hitting “rock bottom” they will still believe the lies they’ve told themselves.

Thirdly, what incentive was there to participate in this survey? From my experience, if you are a pathological gambler you are not going to do anything that will threaten your only method of survival unless you’ve hit rock bottom. Yes, you think you can move the bottom up, but until the gambler gets the issues resolved, they are just white knuckling it.

And fourthly, it’s not about MONEY !! When will the health care providers get this?! A reduction in expenditures at a casino is NOT addressing the problem, it’s only allowing it to continue. Would you allow an alcoholic or drug user to only have a pint vs a quart? Would you ask them to change their drug of choice?

I am just amazed at how research and some counselors approach this obsessive compulsive disorder. Would you say a “cutter” or a “head banger” showed significant improvement by reducing either the size of the cut or the frequency of bangs? Abstinence is the only real measurement that actually represents improvement and even that is questionable unless measured throughout one’s life.

Sorry to sound so “negative”, usually I spend my time looking for the positives. In this case, I appreciate anyone willing to try and do something, no matter the outcome.

Sincerely,

Randy Ringaman, a recovering compulsive gambler

The BASIS Staff April 28, 2016

Dear Randy,

Thank you for writing to the BASIS and for your interest in the WAGER 14(2), Can Treatment be Short and Sweet? A Comparison of Brief Interventions for Problem and Pathological Gamblers. You raised four primary points concerning our review of the Petry, Weinstock, Ledgerwood, & Morasco (2008) study.

Your first comment raised concern about the specific study inclusion criteria (i.e., endorsing 3 or more SOGS items and wagering at least $100.00 on at least four occasions within the past two months). The level of wagering combined with meeting 3 or more SOGS criteria qualified gamblers for the study. Like you, many scientists have expressed a variety of concerns about the accuracy of interpretation of SOGS scores because of the ever-changing definition of problem and pathological gamblers, but researchers have reviewed the literature and confirmed the validity of interpretations based on scores obtained with the original and recent versions of the SOGS (Gambino & Lesieur, 2006; Stinchfield, 2002). However, there also is a body of research suggesting that the SOGS overestimates the extent of problem gambling (Battersby, Thomas, Tolchard, & Esterman, 2002; Gerstein et al., 1999; Walker & Dickerson, 1996).

Second, you suggest that disordered gamblers might not have been honest about their gambling behaviors when responding to therapists’ questions. This is a well-known and legitimate concern; in our review, we recognized self-report as a study limitation.

Third, you question the use of incentives. In accordance with obtaining Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval, the incentives or rewards offered to participate in a study cannot constitute undue inducement or coercion (U.S.Department of Health & Human Services, 2008). Therefore, the incentives to participate in this study were very minimal: $20 in gift certificates for completing the baseline evaluation, and $15 for each follow-up.

This WAGER noted that many disordered gamblers do not seek treatment (Slutske, 2006). However, this observation does not mean that they will have to hit rock bottom before seeking help. In fact, research indicates that many disordered gamblers recover naturally: they are able to recover without receiving formal treatment (Shaffer, 2007; Slutske, 2006; Slutske, Jackson, & Sher, 2003). For instance, Petry et al. observed this phenomenon. They noted that participants in the assessment only control group experienced a decrease in gambling expenditures and had lower SOGS scores at follow-up despite not receiving any of the offered treatments (e.g., brief advice, motivational enhancement therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy).

Fourth, you expressed concern that recovery from gambling cannot be measured only by the amount of money wagered. This is a very important and often overlooked point. Times spent thinking about gambling or emotional distress due to avoiding gambling are important components of gambling problems. It is important to note that the researchers who conducted this study did not use dollars wagered as a sole means of determining the participants’ recovery status (i.e., recovered, improved, or unchanged). The investigators also used participants’ SOGS scores at follow-up. Nevertheless, it is reasonable to consider a decrease in gambling expenditure as a significant improvement in one dimension of problem gambling. Abstinence is certainly one way to measure improvement or recovery from disordered gambling, but we do not agree that it is the only way to measure improvement. For some people controlled gambling appears to be possible after recovery from disordered gambling. This view and the evidence for it are not unique to gambling; harm reduction approaches to treatment have been utilized for alcohol and drug problems (Marlatt & Witkiewitz, 2002).

Again, thank you for your interest in the BASIS and for your comments. We always appreciate reader feedback, questions, and comments.

–The BASIS Staff

References Cited

Battersby, M. W., Thomas, L. J., Tolchard, B., & Esterman, A. (2002). The South Oaks Gambling Screen: A review with reference to Australian use. Journal of Gambling Studies, 18(3), 257-271.

Department of Health & Human Services, U. S. (2008, November 13, 2008). Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP)- OHRP informed consent frequently asked questions. Retrieved February 24, 2009, from http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/informconsfaq.html.

Gambino, B., & Lesieur, H. (2006). The South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS): A rebuttal to critics. Journal of Gambling Issues, 17.

Gerstein, D., Murphy, S., Toce, M., Hoffmann, J., Palmer, A., Johnson, R., et al. (1999). Gambling impact and behavior study: Report to the National Gambling Impact Study Commission. Chicago: National Opinion Research Center.

Marlatt, G. A., & Witkiewitz, K. (2002). Harm reduction approaches to alcohol use: health promotion, prevention, and treatment. Addictive Behaviours, 27(6), 867-886.

Petry, N. M., Weinstock, J., Ledgerwood, D. M., & Morasco, B. (2008). A randomized trial of brief interventions for problem and pathological gamblers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(2), 318-328.

Shaffer, H. J. (2007). Considering the unimaginable: challenges to accepting self-change or natural recovery from addiction (Foreword). In H. Klingemann & L. Carter-Sobell (Eds.), Promoting Self-Change from Addictive Behaviors: Practical Implications for Policy, Prevention, and Treatment (second ed., pp. ix-xiii). New York: Springer.

Slutske, W. S. (2006). Natural recovery and treatment-seeking in pathological gambling: Results of two U.S. national surveys. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163(2), 297-302.

Slutske, W. S., Jackson, K. M., & Sher, K. J. (2003). The natural history of problem gambling from age 18 to 29. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112(2), 263-274.

Stinchfield, R. (2002). Reliability, validity, and classification accuracy of the South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS). Addictive Behaviors, 27, 1-19.

Walker, M. B., & Dickerson, M. G. (1996). The prevalence of problem and pathological gambling: A critical analysis. Journal of Gambling Studies, 12(2), 233-249.