Researchers have speculated as to whether different types of games have different associations with disordered gambling (Ladd & Petry, 2007; Urbanoski & Rush, 2006). However, few studies have tested this speculation in a rigorous manner. This week’s WAGER takes a second look (see WAGER 13(2) for the first look) at Kessler, Hwang, LaBrie, Petukhova, Sampson, Winters, & Shaffer (2008) who examined the epidemiology of gambling and games played. In this WAGER, we will examine the study’s assessment of the distribution of pathological gambling (PG) and recovery across different forms of gambling.

The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NSC-R), a nationally representative sample of 9,282 English speaking adults (Kessler & Merikangas, 2004), used the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI; Kessler & Ustun, 2004) to assess DSM-IV criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) for Axis I disorders among participants. For gambling, the instrument also assessed what types of games each participant played and, for gamblers who experienced problems, whether they experienced recovery (defined as being symptom free for the two years prior to the interview).

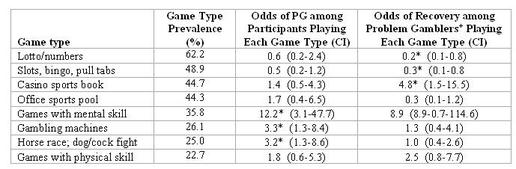

Table 1. Lifetime prevalence of types of gambling and their associations with PG and recovery (adapted from Kessler et al., 2008).

Note. CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio. Presented ORs are adjusted for sex, race-ethnicity-age of onset (AOO) of 1st gambling, years since 1st gambling, and 11 game types.

+ Problem gamblers defined as participants who endorse one or more DSM-IV criteria for PG.

*p < 0.05

More than half (54.7) of gamblers with problems (i.e., meeting 1 or more lifetime DSM-IV criteria for PG) played 7 or more games, compared to 17.1% of non-problem gamblers. All groups favored games in a similar ranked order. Table 1 shows those who played “games of mental skill” (e.g., cards) were more likely to qualify for PG than others. Table 1 also shows that casino sports book gambling at casinos was associated with higher odds of recovery among problem gamblers than other games, whereas slots, bingo, and pull tabs were associated with lower odds of recovery.

These results reflect patterns of association, so we cannot determine whether gambling problems developed as a result of game choice or influenced game choice. Therefore, implicating one game as more dangerous or more difficult to recover from than another exceeds the limits of this study’s methodology.

The study is important for many reasons. It employs a representative sample and used replicable and reliable methods to collect data. The study shows that people with gambling problems do not play games randomly; there are some significant trends associated with likelihood of developing problems and the likelihood of recovery. Future research using longitudinal designs will be necessary to shed light on the psychosocial or game characteristics that account for the patterns shown in the table and, perhaps ultimately, hold potential to improve prevention and early detection.

What do you think? Comments can be addressed to Leslie Bosworth

References

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). DSM-IV: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (Fourth ed.). Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association.

Kessler, R. C., Hwang, I., LaBrie, R., Petukhova, M., Sampson, N. A.,

Winters, K. C., et al. (in press). DSM-IV pathological gambling in the

National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychological Medicine

[preprint available]

Kessler, R. C., & Merikangas, K. R. (2004). The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): Background and aims. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 13(2), 60-68.

Kessler, R. C., & Ustun, T. B. (2004). The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 13(2), 93-121.

Ladd, G. T., & Petry, N. M. (2007). Disordered Gambling Among University-Based Medical and Dental Patients: A Focus on Internet Gambling. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 16(1), 76-79.

Urbanoski, K. A., & Rush, B. R. (2006). Characteristics of people seeking treatment for problem gambling in Ontario: Trends from 1998 to 2002. Journal of Gambling Issues, 16.

Judy April 28, 2016

Hello,

I had a couple of questions/thoughts about the last two Wagers:

1. “gambling machines” — does this mean video poker and/or ??

2. In general, I think of problem gamblers as usually attached to one, maybe two types of games. (“I play blackjack, but occasionally will play x”. “I’m a poker player.”) So, I was surprised at the statement that “More than half of gamblers with problems…played 7 or more games…” . I take this to mean that if the gambler said yes to any of the DSM criteria during their lifetime, the number of games reflected any they had ever played? So, my question is around whether or not there was any indication that the game they played was part of the era of problem gambling (did they play bingo once as a kid, but then 20 years later start playing the dogs daily– and that would count as two games? Also, there is some thought, probably not researched, that over the lifetime of a gambler, the games may move from more skill/action to more luck/escape games. (I’ve read the theory, don’t know the origin).

3. Lastly, if I read this correctly, cards, sports betting, etc. are up to 20 times more likely to be associated with problem gambling than slots. Am I reading this correctly? I find this quite different than clinical experience (and might be indicative of who seeks treatment, who doesn’t). And the recovery rate is even higher. I found this even more surprising.

Thanks for your help,

The BASIS Staff April 28, 2016

Dear Judy,

Thank you for questions.

“Gambling machines” is a broad phrase encompassing four different terms: “slot machine,” a “fruit machine,” a “poker machine,” and a “video lottery terminal (VLT).”

More than half of problem gamblers (who met 1-4 lifetime criteria) played 7 or more games. This means that they played 7 different games one or more times at any point during their lifetimes.

Although cards and sports betting were about 20 times more likely to be associated with problem gambling than slots, this estimate is imprecise because the sample of problem and pathological gamblers was quite small. This creates large confidence intervals, so we must remember to interpret all findings about pathological and problem gamblers in the study with caution.

Clinical experience and clinical epidemiology indicate that pathological gamblers are more likely to play slot machines than most other games, as evidenced in the Iowa Gambling Study. Again, we must interpret these findings cautiously because because the Iowa study sample represents treatment seekers only. There was no one who received treatment in the Kessler (2008) study. It is likely that that evidence obtained from clinical populations differs from evidence generated by household populations. Throughout their lifetime, disordered gamblers might change their game of choice, and different games might have different risk factors. For current research on this subject, we recommend the following article, which compares actual online betting activities of heavily involved bettors to activities of less involved bettors over a two year period:

Again, thanks you for your interest and for writing to the BASIS

–BASIS Staff

References

LaBrie R.A., Kaplan, S.A., LaPlante, D.A., Nelson, S.E., and Shaffer, H.J. (2008) Inside The Virtual Casino: A Prospective Longitudinal Study Of Actual Internet Casino Gambling, European Journal of Public Health. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckn02.

This paper is available on our website at http://www.divisiononaddictions.org/html/library.htm.